The annual Bradley Symposium meetings of the Hudson Institute’s Bradley Center for Philanthropy and Civic Renewal are always thought provoking, erudite discussions of conservative political thought with lessons and implications for nonprofit sector organizations. At Hudson’s most recent convening of big thinkers, Weekly Standard editor and television commentator William Kristol led a challenging discussion about the intellectual and political legacy of the late Harvard University political science professor James Q. Wilson.

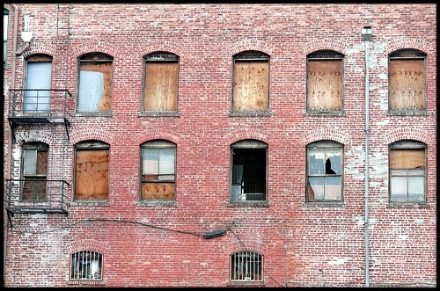

If you can’t quite place Wilson, you might remember his “broken windows” theory of crime prevention, first articulated in an article he co-authored for The Atlantic. The idea was that keeping the urban environment in good shape—that is, repairing the broken windows and keeping up properties—is important to slowing and reversing criminal behavior. New York City and others have adopted the broken windows strategy in crime prevention by stepping up police actions against graffiti vandals and “squeegee guys” as steps in deterring more serious criminal behavior. Plenty of community-based anti-crime nonprofits implicitly or explicitly adopt elements of the broken windows strategy by combining neighborhood upkeep with crime prevention.

Wilson 101

At this year’s Bradley Symposium, Boston College professor Shep Melnick, like Kristol a former student of Wilson’s political science classes at Harvard, offered a summary of three of Wilson’s major books with clear insights into nonprofit issues of today, whether one buys the analysis or not. In The Amateur Democrat, Wilson studied club politics in three cities, suggesting that the “amateur spirit,” according to Melnick, was becoming more pervasive in American politics. For “amateurs” in political organization, the motivation for political action is the ends to be achieved. Melnick’s interpretation of the lessons of The Amateur Democrat is that the focus on ends in politics today is, as Wilson worried, a shift of power away from people who are good at building compromise and consensus toward people who are focused on identifying and refining dissent. He suggested that this is a move away from consensus building toward confrontation. In some ways, that would certainly characterize the political styles of the Tea Party and the Occupy Wall Street movement and the increasing political polarization in American politics in general.

In Political Organizations, Wilson addressed the incentives for joining political organizations. One such motivation includes solidarity incentives, the desire to belong to a group of like-minded people or people with a similar status or other characteristic. Another such motivation is purposive incentives, the feeling of contributing something to an important cause. Melnick’s interpretation of Wilson’s analysis is that purposive incentives ask members for small contributions to address a very large social or economic problem. As a result, these organizations tend to be staff-dominated. Because the members are tied to big issues, the members lead the groups to take aggressive positions, Melnick said, and make it difficult for staff to make pragmatic political decisions.

The third Wilson book Melnick discussed was Bureaucracy, which addressed the conflicting and multiple goals laid on government bureaucracies. Melnick suggested that Wilson saw effective, autonomous bureaucratic agencies as likely to develop a sense of organizational mission and culture that makes them easy to run, perhaps because of the mission identification and commitment of the staff. For the same reason, Melnick noted that Wilson saw bureaucracies as equally hard to change. While Wilson was writing about government bureaucracies, the applicability of the analysis to nonprofits is not hard to see.

With a little adjustment for terminology from more than four decades ago, Wilson’s commentary in his article in The Public Interest titled “The Bureaucracy Problem” contains insight into the challenge of nonprofits, specifically concerning the creation of leaders. Among his explanations of the limitations of large bureaucracies, Wilson wrote:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“(G)ood people are in short supply, even assuming we know how to recognize them. Some things literally cannot be done—or cannot be done well—because there is no one available to do them who knows how. The supply of able, experienced executives is not increasing nearly as fast as the number of problems being address by public policy. All the fellowships, internships, and ‘mid-career training programs’ in the world aren’t likely to increase that supply very much, simply because the essential qualities for an executive—judgment about men and events, a facility for making good guesses, a sensitivity to political realities, and an ability to motivate others—are things, which if they can be taught at all, cannot be taught systemically or to more than a handful of apprentices at one time.”

Testing Wilson’s Ideas Today

In our politically polarized society, there are likely lots of people who will dismiss Wilson because of paeans from the likes of Rudy Giuliani. The former Republican mayor of New York City wrote a tribute to Wilson after his death this past spring, noting, “When I became mayor in 1993, I couldn’t wait to test Wilson’s theory. I began, with police commissioner Bill Bratton, to focus on the squeegee guys who disturbed and frightened visitors to the city, wiping down their windshields and demanding payment. We had assumed that there were hundreds but found that in reality there were just a handful. We moved them off the streets, and there was an immediate feeling that low-level criminals were no longer in control and that New York City was livable again.”

The mere mention of Giuliani is like screeching nails on a blackboard to some observers, but Wilson’s ideas are still actively tested by nonprofits and cities. Wilson’s “broken windows” co-author, George Kelling, is testing the broken windows concept in a relatively stable Detroit neighborhood, Grandmont-Rosedale. The key to the strategy is getting neighborhood residents to observe and report suspicious activity and to have police identify and make house calls on parolees and others who were once incarcerated to let them know about available social services and about the neighborhood residents watching them.

Grandmont-Rosedale is a neighborhood fighting to be preserved amidst the decay and destruction of neighborhoods surrounding it. While fingering ex-felons for police visits may strike some as somewhat draconian, the overall program of a community and its local police collaborating to eliminate multiple levels of crime and, in their estimation, the social and physical conditions that support crime, is pretty much a part of the theory of community policing that many nonprofit community development corporations typically pursue. For example, the Community Safety Initiative of the Local Initiatives Support Corporation exhibits Wilsonian concepts of community policing, such as the Olneyville neighborhood in Providence, R.I., where nonprofits such as the Olneyville Housing Corporation and the local police work together on a nuisance abatement task force to clean up run-down properties and get rid of abandoned cars in the neighborhood.

According to a LISC report on its Community Safety Initiative, “Build cohesion in the community and reverse its physical blight, and you go a long way to curbing delinquency, petty crime, and eventually more serious adult crime as well.” In Melnick’s interpretation, Wilson’s broken windows theory is really about the “collective power of culture.” Without referencing Wilson, LISC’s expression of the concept is this: “Making one community safer is not a matter of moving crime away from the neighborhood, but of discouraging criminality at its source. Restoring order to chaotic physical and social environments not only makes those environments less hospitable to crime, it sends a signal to the residents—especially the young people who live in and near the revitalized area: Lawfulness and constructive behavior are important. People care when norms are violated.”

Over the years, the Bradley Symposiums have been predicated on the notion that “big ideas” drive a significant part of American politics. Big ideas need to be understood, debated, and assessed by both sides so that supporters understand their limitations and opponents see some aspects of their value. Reviewing the ideas of the late James Q. Wilson that have had an impact on politics and on nonprofits is a worthwhile venture for conservatives who see Wilson as one of their camp even though he had much broader ideas and ideals than today’s conservative political orthodoxy. Such a review is also a good idea for liberals who wonder how a generally conservative political theorist like Wilson understood some of what they do and why they do it.