“RAINY WINDOW” BY CHRISTINA KERNS/WWW.CHRISTINAKERNS.COM

If there is any good to emerge from the financial upheavals of the past few years, it may come in the form of nonprofits’ realization that they cannot be rainy-day, ambivalent advocates on the issue of budgets and taxes. Whether they are advocates for children’s services, public safety or public health, or poverty prevention or remediation, it is no longer possible to ignore that they are in the business of budgets and taxes. The federal, state, and local budgets enacted and the taxes deemed necessary to support them will constrain or support the programs that nonprofits espouse.

Indeed, one might say that budgets and taxes are every nonprofit advocate’s second issue.

If that is the case, advocates across a broad spectrum of issues must stop treating messaging on budgets and taxes as an afterthought or intermittent necessary evil. They must bring to their advocacy repertoire a more refined, reliable approach to explaining how budgets and taxes affect children and family services, public safety, and many other issues. And in order to shift the discourse on public funding over the long term, they must do this year round, not simply at key points in the visible budget battles. Advocates must also consider the intersecting effects of how they communicate about budgets and taxes and their core issues.

Strategic Frame Analysis™

While many nonprofits have developed strong communications practices on their focal issues, very few have questioned how these strategies affect their ability to explain fiscal issues within that context. Put another way, what happens when you combine the framing strategies you use to advocate for a primary issue with the frames used to advocate for the related, secondary issue of public funding? Do those framing strategies yield “toxic combos” that undermine the compound message? Or, does the strategy allow for an integration of both issues into a powerful story that lifts support for progressive fiscal policies?

In this article we use the perspective of Strategic Frame Analysis™ to explore these sorts of questions, mapping the terrain that advocates need to cover in becoming more effective communicators about budgets and taxes.1 We do so because we believe—and numerous social scientists concur—that the conscientious reframing of issues is imperative to galvanizing public support.2 Political scientist Shanto Iyengar has shown, for example, that how people think about poverty is dependent on how the issue is framed: when framed structurally, people assign responsibility to society at large; when framed as a specific instance of a poor person, responsibility is assigned to the individual.3 But changing the way we frame issues requires that we understand which frames to use and which to eschew, and why. Strategic Frame Analysis™ not only examines how issues are routinely framed in news media and public conversations but also evaluates the merits of these frames based on the cultural models they ignite in mind—or their frame effects.

Beginning in late 2008, the FrameWorks Institute began a multiyear investigation of American thinking about budgets and taxes. Building on FrameWorks’ research on how Americans think about government, the goals of this project were to understand the underlying assumptions Americans have about budgets and taxes, and to develop more productive strategies for communicating about these issues. With funding from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, we translated these findings into an interactive game tool that allows advocates to explore the intersections of education and early child development with budgets and taxes.4 The insights we offer here are based on this research and our experiences advising dozens of nonprofit groups in related message framing.

The Drip-Drip-Drip Hypothesis

Media theorist George Gerbner coined the term “drip-drip-drip” to refer to the effects that emerge after steady long-term exposure to media frames. In this process, ordinary Americans going about their everyday lives encounter frames that seep into their thinking, connect to their internalized ideas about how the world works, become chronically accessible, and eventually drive thinking. What is present in the drip-drip-drip of messages about budgets and taxes? Budgets are rarely present in the flow of frames except as they relate to (1) government excess or incompetence, and (2) household budgeting. But taxes are ubiquitous, and not just in politics—a steady drip-drip-drip of meaning is omnipresent in ads for accounting and tax preparation services, in news you can use for April 15 tax filing, and in consumer tips about buying or selling a home or sending your child to college. And what do we learn from this faucet of frames? It’s a pretty consistent message, as codified in this (paraphrased) ad campaign from TurboTax: It’s your money. We know how hard you work for your paycheck. You should have the power to keep as much as possible.

Far from an innocuous invitation to buy a product, the framing in this advertising campaign tells us that advertisers are playing to the way people have come to think about taxes: they rob people of their earned income, they violate fundamental American principles that reward hard work, and it is the right of every American to resist taxation. These frames are designed to connect to Americans’ deeply held cultural models that shape and constrain how people think about an issue and the solutions they see as effective and appropriate.5 People’s mental muscles are being exercised with great regularity on this issue, building strong connections between the term “taxes” and these deeply held cultural models of how the world works. Getting out of this situation will require nonprofit communicators to become highly strategic and intentional in the way they wield new frames to break down these forged connections.

What’s in the Swamp?

Most approaches to communication make it a priority to anticipate and understand the audience. Strategic “framers” approach this task by seeking to understand the cultural models accessible to people when they think about a particular issue, or the “implicit, presumed models of the world that are widely shared and that play an enormous role in the public’s understanding of that world and their behavior in it.”6 For example, the American cultural model about work would include the widely shared notion that work should be rewarded and that people who don’t work shouldn’t get the same rewards as those who do. A steady diet of stories in news media and public discourse plays to these cultural models, enhancing our ability to use them as reliable, default meaning-making devices. In short, cultural models help us to filter and categorize new information, determine relevance and priorities, and guide our decision making.7 When we choose how to frame a message, we must understand what cultural models we are playing to, and with what consequences for our positions and policies. And, more often than not, the choice of frames already dominant in discourse yields no movement in public thinking beyond the status quo.

In explaining this complex array of implicit concepts that the public uses to make sense of the world on any given topic, FrameWorks appeals to the metaphor of a “swamp.” When social scientists examine what’s at play in people’s reasoning, they do not witness a barren landscape but rather a complex, vibrant, messy, “swampy” ecology of cultural models that people have stored away over time and bring forward as necessary to explain their world. The “swamp” metaphor can help advocates appreciate several fundamental characteristics of cultural models:

- People hold multiple cultural models on any given issue. In our research, we often observe an informant arguing passionately for one way of thinking, only to see him or her endorse an opposite position in the next breath.

- Cultural models are neither inherently good nor inherently bad; it depends on where you want to lead people. Some parts of that swamp will prove useful for growing your advocacy goals—places where you can nurture positive support for your progressive policies. Other parts are full of alligators, dangerous currents, and sinkholes—places where your policy proposals are likely to meet tough opposition from entrenched habits of thinking.

- Cultural models are directive. That is, whatever part of the swamp you “re-mind” people about will be used by people to “think” or process your issue. The lesson is clear for advocates: you must avoid activating cultural models that take people in the wrong direction and focus on invigorating only those that allow people to reason more productively and expansively.

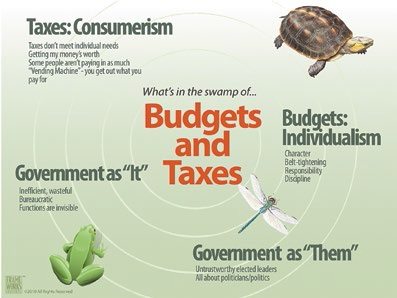

Let’s apply cultural models theory and our swamp heuristic to the issue domain of budgets and taxes. Think of communications as navigating the swamp and mapping it in order to determine what you have to work with and what you will need to avoid in the future. To map the swamp of public thinking about budgets and taxes, FrameWorks conducted twenty-five one-on-one, in-depth interviews with members of the public, followed by peer-discourse sessions with fifty-four adults divided into small groups. To find ways around the traps lurking in that swamp, we conducted an experimental survey with 6,700 Americans, documenting the effects of various “reframes” in inoculating against unproductive models and pulling forward more productive ways of thinking. Here’s what the swamp of budgets and taxes looks like:

Relating budgets to taxes. A notable characteristic of the swamp is that in public thinking, budgets and taxes are disconnected concepts.8 FrameWorks’ informants struggled to link the two concepts, and were consistently unable to explain decisions and respond to problem-solving tasks that required their integration. This finding reveals a highly problematic cultural understanding—one that sets up a disjointed conversation in which budgets are not related to nor integrated with taxes. Reasoning in this way, people cannot see a system in which the country sets both short- and long-term priorities, and pays for them with revenues from past taxes as well as projecting for future needs. If they cannot see a system, the need to reform the system is equally “hard to think.” Divorced from this integrative relationship, the default models of budgets and taxes are not required to make sense with respect to each other and thereby elude an important reality check. At the same time, when FrameWorks’ researchers forced informants to relate budgets to taxes, there emerged a strong cultural model in which inputs must equal outputs. That is, the “common sense” that most Americans bring to these issues asserted a one-to-one correspondence in which balance is best and inputs can occasionally exceed outputs, but outputs can never exceed inputs without the system’s collapsing.

Why is this problematic? Many economists and public policy experts believe that the current narrow discourse on public budgets and the role of the American tax system does not reflect the full range of policy thinking necessary to solving the problems that assail the country. Most recently, Harry J. Holzer and Isabel Sawhill pointed out:

Alarmists who call for immediate spending cuts and immediate reductions in our debt-to-GDP ratio (now at 73 percent) overstate the dangers of current levels of spending and debt, and they understate the damage to employment and economic growth that result from recently enacted belt tightening. That tightening, including the effects of provisions enacted in both 2011 and 2013, is expected to halve the growth rate in the gross domestic product this year, according to the Congressional Budget Office. This self-inflicted wound to the economy and to jobs makes no sense. If anything, we should be using this period when workers are underemployed and firms’ physical plant and financial resources are underutilized to improve productivity by investing more in infrastructure and job training.9

Yet current American discourse on the role of government and its tax systems is not about job training, infrastructure growth, or even the necessity of a sustainable system with a robust social safety net that invests in human capital of all members of society. As such, the public’s myopic outlook inhibits any opportunity to view public budgets and taxes as the tools society needs in order to meet its goals for the future.

The household budget model. We are far from experts on fiscal issues, but we do understand how the cultural models available to people on budgets and taxes prevent the broader conversation that experts would like them to join. When forced to think and talk about budgets, our informants defaulted to several powerful models. First, they individualized the topic, often equating budgets and budgeting with the household kind. Once thinking from this model, people draw upon the personal qualities they believe make for good household budgeting: notably, a good household budgeter has “character”—or moral and ethical traits—that allows him or her to overcome selfishness and self-indulgence. Taking responsibility for his or her household, the budgeter exercises belt-tightening discipline, resulting in shared hardship that is tough but builds character in everyone. Like dieting, budgets were described in terms of strict behaviors: “taking control,” “sticking with it,” and avoiding excess. In addition to focusing all attention on individual (moral) traits of the budgeters, this cultural model assumes that budget balancing is the ultimate goal. Budget experts reject this analogy because it overly simplifies and distorts the public budgeting process. For instance, the household budget model works with short time frames—paycheck to paycheck, month to month, and year to year. In contrast, public budgets are not tied to immediate revenue but rather to long-term needs. Government budgets need to fund very large investments (i.e., infrastructure) that must be amortized over time. The taxes we pay today do not fund our medical or technological advances of next month but those far into the future. In addition, the household budget model holds that short-term sacrifice necessarily leads to long-term benefits, but this analogy does not hold for public budgets: sometimes austerity results in bad financial outcomes.

The `is instructive in demonstrating how cultural models shape and constrain public thinking. Once this quickly accessible, concrete analogy is evoked to explain the abstract, complex process of public budgeting, it will influence the interpretation and assessment of information on the topic. It brings with it a package of assumptions about the character traits of good household budgeters—thinking that easily leads to opinions about the government’s lack of “discipline,” or inability to prioritize needs over wants.

The household budget model is also instructive in illustrating that common tropes are often communication “traps.” Advocates are understandably attracted to this simple analogy that seems so popular with the public, but it is ultimately unproductive in advancing the case for public support of critical initiatives. There is an important lesson to be extracted from this alligator in the swamp: not everything that people are familiar with works to one’s advantage. The goal of communications is not simply to relate to or “resonate” with people’s prior convictions but rather to guide their thinking and opinions toward a desired position. To accomplish this, strategic framers look to research that describes the available cultural models, consider the implications of each, and choose to build a framing strategy on the cultural models that work to their advantage in explaining progressive programs and policies.

The interpretation of “fairness.” Now let’s take a look at what’s in the swamp of thinking about taxes. Just as the cultural models for budgets tended to be highly individualistic, so the default models about taxes focused more on individual than collective needs. One of the most commonly expressed beliefs about taxes was that they undermine Americans’ ability to meet their needs. At the core of this model is the belief that personal earned income should be dedicated to earners’ immediate needs as individuals and families, and that government “takes money away from [us].”10 Closely related to this way of thinking is the consumerist assumption that people should get their money’s worth: if taxes are paying for goods, people should be able to immediately see and appreciate the thing they have purchased. In other words, people have a model that, like a vending machine, suggests taxes in, goods out, in exact proportions.

This vending machine cultural model can lead to faulty thinking about budgets and taxes. Many of the “goods” purchased with tax revenue are intangible, invisible, or ill understood as resulting from public funding. Without considerable prompting, such collective benefits as education, highways, social security, public health, and safety are not “top of mind”; indeed, they are often not recognized as “public” goods. The collective benefits that taxes support are masked by the consumerist model. If taxes are all about benefits accruing to individuals in the exact amount that individuals put in, there is quite literally no space for benefits from taxes that don’t accumulate to individuals, or that may tax some people more than others in order to support the common good.

The interpretation of “fairness” is similarly influenced by consumerist thinking. In the public mind, the default definitions of tax “fairness” involve either complete standardization (everyone should pay the same amount) or fee for service (everyone should pay only for the services he or she uses, and in proportion to how much is used). These powerful models guided thinking in everyday conversations among our informants, despite the fact that there was almost universal consensus that wealthy people and corporations should bear greater burdens in the tax system. And herein is another important lesson: when cultural models are vivid and well exercised, they tend to trump other opinions we hold.

Perceptions of government. While the concepts of budgets and taxes are disconnected from each other in public thinking—like Mars and Venus, in the title of a FrameWorks report11—they are nevertheless perceived to orbit within the same solar system: that of government. How people think about government flavors their understanding of both budgets and taxes—what these are and should be, how they work or don’t, and whom they benefit or disadvantage.12 As FrameWorks’ research shows, cultural models commonly used to think about government pollute the swamp of budgets and taxes with strong, entrenched currents. On the one hand, there is the view of government as “it”—or a big, bloated bureaucracy of undifferentiated parts that is wasteful and out of control. Reasoning from this model, Americans assume that “it” will try to take their hard-earned funds, be unable to control its own excessive spending, and act irresponsibly with “someone else’s” (their) money. On the other hand, there is the view of government as “them”—or an array of untrustworthy politicians who are using Americans’ hard-earned funds for their own purposes. It is important to note how individual intentions and character traits flavor this discussion; here the moralism of the budgets and taxes discussion draws further credence from the immoral context that characterizes the domain of government. “What would you expect from government,” people ask, “if not to take your money and spend it on some crazy thing you will never see?” And, as scholar Deborah Tannen has remarked, “The world, being a systematic place, confirms these expectations, saving us the individual the trouble of figuring things out anew all the time.”13

Navigating the Swamp Is Hard Work—

You Need Gear

What are nonprofit communicators to make of or do with this swamp of highly patterned, well-traveled ways of thinking about budgets and taxes? As with any journey, you are going to need a map to get from where you are to where you want to go. The swamp we’ve just described tells us where people are stuck and what concepts routinely and predictably inform their conversations and opinions. But the dominant cultural models are not the only ways people think about these issues. As we saw with the issue of fairness, people have other ideas about how the world should work—they are just less formed, less practiced, or sketchier than those that get exercised daily in public discourse. The job of strategic reframers is to identify more useful, albeit rare or recessive, models hidden in the swamp, and to figure out how to pull them forward.

If cultural models research provides a map of public thinking, then framing strategies might be thought of as the gear needed to get through the swamp. Strategic Frame Analysis™ points to two powerful reframing tools that have performed consistently to invigorate more productive models of budgets and taxes, of government and the common good. These tools cue up concepts already in mind but less developed than the dominant cultural models we’ve observed in the swamp. Think of them as big magnets we wave over the swamp in order to pull up what’s valuable.

Tools for Reframing

When we scrutinize the swamp of existing cultural models of budgets and taxes, we find a notable lack of ideas about the end goal. Not only are taxes seen as an end in themselves, the budget process is routinely thought of as a game that government plays with other people’s money—a kind of macabre Monopoly. How might we remind people what’s at stake in setting priorities for the country and raising the funds necessary to support those goals? Can we realign budgets and taxes behind larger ideas about how the world should work, beyond consumerism and individualism?

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The values tool. The first tool in the reframing tool kit of Strategic Frame Analysis™ is values, or those enduring beliefs that orient individuals’ attitudes and behavior and form the basis for social appeals that pull audiences’ reactions in a desirable direction.14 Values hold promise for redirecting thinking on these questions, but it’s important to make sure that the right value is assigned to the job. To ground framing recommendations in solid scholarly research, FrameWorks’ comprehensive experimental survey tested the frame effects of four values on support for progressive tax and budget attitudes and policy preferences. Those values were: Crisis, Prevention, Common Good, and Future.15 These values were not chosen randomly; rather, each represents a hypothesis about which framing might be most effective in reorienting public thinking on budgets and taxes.

The Crisis value is used frequently by policy experts and advocates for progressive budget and tax reform. That is, it is one of the values to emerge from the field of practice. Based on our prior research on social issues, we hypothesized that Crisis would not elevate public support for policy, as the tone of the value primes the public to see the problem as overwhelming and intractable. Thus we thought it would likely push people to disengage from the issue, ignoring the possible efficacy of proposed solutions. Additionally, we predicted that “crisis fatigue,” or the public oversaturation with this way of thinking about the world, would blunt or undermine frame effects.

The Prevention and Common Good values were included on the basis of positive results in previous FrameWorks research, in which similar contours of public thinking presented themselves. For instance, in work on reframing racial disparities, Prevention helped people to move past thinking that was fixated on the present-time horizon of social problems, and we hypothesized that Common Good would be effective in reminding people of the public goods that are supported by taxation. The Future value emerged during our qualitative work on budgets and taxes, having been employed quite skillfully by one of the participants in our peer discourse sessions. Her ability to change the entire conversation of a diverse group of participants alerted us to the potential of this value, and we subsequently tested it in other phases of the research.16

FrameWorks’ experimental design involved exposing participants to a short paragraph explaining one of the values, and then probing their attitudes toward the topic as well as their support for a wide range of progressive policies. (Values frames are judged effective if they achieve statistical significance in raising support for policies, compared to the null condition in which people get no value but are simply asked about their attitudes toward budgets and taxes and their support for policies.) In the case of the experiment on budgets and taxes, the policy list included everything from expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit to rejecting flat taxes and budget cuts. Then, we tested the synergistic effects of each of our four candidate values with a secondary paragraph about budgets and taxes—that is, could the value gain strength when applied to the issue domain?

One of the tested values achieved a statistically significant result in moving attitudes and policy preferences, but in a negative direction: Crisis. As predicted, framing budget issues in terms of Crisis depresses, rather than increases, support for public budgets and related progressive policies. What worked? One value—Prevention—outperformed all others in moving attitudes and policy support toward the more progressive end of the scales. Compared to the control group that received no values frame, priming subjects with the value of Prevention increased support on the attitudes scale by 12.4 points, a statistically significant change. When the paragraph about budget and taxes was added, it enhanced the attitudes effect to 17 points. On the policy preferences scale, the results of a Prevention frame showed a trend in a positive direction, though these results did not achieve statistical significance. No other values frame achieved significance.

On the Prevention Value

Our state/country could do more to prevent problems before they occur. Instead of postponing our response to fiscal problems, we could use our resources today to prevent them from becoming worse. When we postpone dealing with these problems, they get bigger and cost more to fix later on. We would be better off in the long run if we took steps today to prevent the fiscal problems that we know will affect the well-being of our state.

How does Prevention help us? First, it conveys the idea that acting now to prevent problems from becoming worse is the responsible thing to do, while postponing action will have consequences for us all. Moreover, it establishes the idea that using resources that we have today can help us to solve problems. These ways of framing the issue pull forward other available ways of thinking about what is moral and responsible behavior than merely tightening one’s belt. They also put forward goals that are bigger than one’s own consumption. In this way, the value of Prevention performs that magnetizing function over the swamp of cultural models, pulling forward what’s useful and leaving the rest behind.

The explanatory metaphors tool. The second reframing tool FrameWorks commonly advances is the explanatory metaphor. This device is especially useful when public thinking reveals “cognitive holes”—such as the missing concept of the relationship between budgets and taxes. To fill these “holes” in public understanding, FrameWorks develops and tests explanatory metaphors that make concepts easier to understand by organizing information and comparing it to something concrete, vivid, and familiar.

We set out to use metaphor to address some very specific problems lurking in the swamp. In order to use metaphor to full advantage as a frame tool, we homed in on several aspects of the perceptual problems. Specifically, we sought to address the disconnect between budgets and taxes. An effective explanatory metaphor would have to generate this connection in order to improve understanding of budgets and taxes, helping people relate and integrate the two concepts. We also sought to ensure that the metaphor addressed the need for (1) a way to think beyond or outside of dominant cultural models (e.g., wasteful and broken government); (2) ways to think productively about old tensions (e.g., taxes versus spending); and (3) ways to encourage individuals to conceive of their own roles as political actors (agency).

One metaphor, forward exchange, emerged as powerful from FrameWorks’ iterative process of qualitative and quantitative testing.

On the Forward Exchange Metaphor

Budgets and taxes occur in a system of forward exchange. We pay taxes forward—not for immediate exchanges for public goods but so that we can have them available in the future. The public goods a community has today, such as schools, highways, and safety systems, weren’t only paid for by taxes its members just paid or are about to pay—they were also paid for in the past, by taxes that were budgeted then to meet the community’s needs now. So we can say that a good public budget is one that plans for the future and for the unexpected. And we can also say that good taxes are the ones that allow a community to pay for the public goods and services for which it has planned.

Not only was the forward exchange metaphor found to enable the connection to be made between budgets and taxes (whose relationship the public needed to understand) but it also (a) inoculated against the dominant frames of government as wasteful and bureaucratic; (b) enabled people to think about how taxes and public goods and services are not immediate exchanges, and that budgets spread out the cost and benefit of public goods over time; (c) allowed people to see that taxes have a purpose and are shared responsibilities rather than individual burdens; (d) encouraged individuals to consider their own role in solutions; and (e) significantly shifted respondents’ attitudes about budgeting and taxation in a progressive direction.

Toxic Combos

What happens when you apply these potent values frames to the issues that advocates care about, whether mental health, education, or early child development? As we acknowledged earlier, we recognize that budgets and taxes are not the prime issue of concern for most nonprofits. We are arguing for a more strategic approach to including this secondary issue in advocacy communications. Such an approach would require recognition of the way people come to the issue (their swamps of cultural models), and would use tested and proven frame techniques to navigate around the communications pitfalls.

It is our observation that this is not the current practice in the field. Nonprofit communicators are very smart about framing their own top issues but append a budgets-and-taxes message onto them as an afterthought. The danger in so doing is that they run the risk of igniting those “toxic combos” referred to earlier—alignments of issues that are fraught with the same unproductive cultural models. When nonprofit communicators inadvertently cue up a cultural model with their framing of budgets and taxes, they also reinvigorate its negative effects on their own issues.

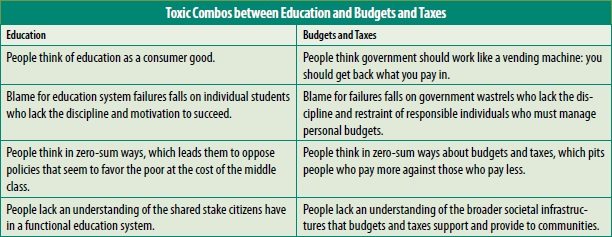

Education and budgets and taxes. Let’s look at how the issue of education overlaps with budgets and taxes in relying on an unproductive model of individualism. We have described Americans as thinking about many social issues in distinctly individualized, consumerist ways. Where education and budgets and taxes are concerned, Americans believe that “you should get out of the system no less than what you put in.” They are wary of free riders who don’t pay their fair share and take more from budgets and public education than they deserve. FrameWorks research shows that education as a collective investment is not on people’s radar. (These “individualist” tendencies can be seen in the toxic combos outlined in the above table.)

Avoiding such toxic combos is but one reason why nonprofit communicators need to pay more attention to the framing of budgets and taxes. There are numerous ways to avoid these and other toxic combos, but to learn how to do so, nonprofit communicators will have to agree to get in the game of reframing the swamp of budgets and taxes. FrameWorks offers a simple, painless, costless way to do so—it’s our online advocacy game, SWAMPED! Here you will encounter dangerous predators and hazards in the swamp of public thinking that threaten to sink your communications message. In this adventure, you will navigate the challenges in the Education or Early Child Development landscape as well as those that cross over from the land of Budgets and Taxes. After you have charted the path with our communications canoe, you can begin to help your organization, the coalitions it leads, and the communities it informs to think more productively about the intersection of your issue with the national conversation about budgets and taxes.

The following are four illustrations of how nonprofit communicators might begin to engage in reframing their issues at the intersection of budgets and taxes:

1. Framing state budget priorities. Advocates have characterized the current decisions facing their state as the proverbial fork in the road—with raising revenue as one possible direction and cutting spending as the other. This false choice is countered with the statement, “It’s not one or the other . . . it’s a balanced approach.”17 When making this claim, communicators trigger consumerist cultural models in the public’s thinking, in which the focus is on the assumption that input must equal output. This way of framing the issue inadvertently leads the public to think about budgets and taxes like a household budget, in which immediate income must balance immediate expenditures. As a consequence of this framing, the public is unable to understand how budgets and taxes might be used to meet our societal goals, such as investing in opportunities, resources, and supportive services for children that can yield long-term benefits for the entire state. Nonprofits can overcome this framing trap by using the forward exchange metaphor to explain that budgets are instruments for planning our future. Doing so will help bring the collective nature of the budgeting process into the public’s focus. Also, the Prevention value can help frame the importance of setting state budget priorities as collective and solvable.

2. Framing charitable deductions. Nonprofit leaders have been focused lately on saving the charitable giving deduction—“Both by reducing the charitable giving incentive and cutting federal programs, nonprofits would face increased public demand for services with fewer resources.”18 Locked in a “starve the beast” mentality with respect to government, Americans are likely to see nonprofits as regrettable casualties of this more important goal of shrinking the bloated bureaucracy. Moreover, such crisis frames applied to taxes, tax policies, and deductions make the issue more about getting the wealthy to donate funds than about how effective public tax policies can help nonprofit programming—which, in turn, contributes to the priorities we set as a society. Nonprofit communicators can reframe the conversation by using the forward exchange metaphor to clarify that what the public programs and services nonprofits provide, and which are also paid for by public taxes, are collectively beneficial. Doing so will help shift the focus from politicians and sequestration politics to policies that grow the economy and facilitate the participation of nonprofits in that goal.

3. Framing April 15. Every year during tax season, nonprofits participate in campaigns and share information with the public about a variety of tax exemptions, deductions, credits, deferrals, and special rules that allow individuals and businesses to reduce the amount of state tax they owe. In doing so, they may say, “It’s your money, you’ve earned it, claim it now,” to emphasize that such credits are vital to ensuring that working families do not miss out on valuable incentives that can alleviate the burden they face when trying to make ends meet.19 These sorts of statements trigger cultural models of government as a force to be resisted and of zero-sum thinking that individualizes the impact of taxation by suggesting that our tax system should be operating like a vending machine. As these statements reach a broader audience, they encourage the public to think that some people are getting more than they pay in, thereby obscuring the purpose of budgeting and taxation: to meet the needs for all members of society. To overcome this communications challenge, nonprofit communicators will need to avoid talking about fairness as a goal for evening out the “paying field” when it comes to taxes and tax reforms, and talk instead about how important it is to prevent communities from deteriorating by ensuring that people can maintain property, support their local institutions, and participate in the local economy.

4. Framing budget cuts. When nonprofit leaders speak out about the impact of budget cuts on, for example, education and youth mentorship programs, there is a tendency to frame the issue as “We cannot let these kids lose their adult role models.”20 This serves to trigger toxic combos of cultural models about family responsibility for children, defining the issue as an individual-level problem. Relatedly, such statements trigger cultural models about government as wasteful, since they fail to explain why education and mentorship should matter to all, and how budgets and taxes are infrastructures that support entire communities—both in the long- and short-term—by paying for such important programming. Key to navigating away from this particular toxic combo of cultural models is making the case for linking funding for educational (e.g., after-school and mentorship) programming to tax resources as a solution that benefits the country as a whole.

Conclusion

In sum, knowing what’s in the swamp of cultural models, and what frames can be mobilized, can help you to avoid entrenched ways of thinking, and expand constituencies for your policy agenda. Above, we gave an example of a toxic combo between education and budgets and taxes that led to defining an issue as an individual-led problem. An example of a more constructive frame would be: Our education and early child development systems are crucial in preparing our country to meet its future challenges. Instead of promoting fiscal policies that only work for some of the nation’s children, we should use our public budgets to develop solutions that serve the common good for all. We need to make sure we don’t go backward, or leave our children with outdated skills and our communities without the workers and stakeholders they need. We can prevent that from happening. When we pay our taxes, we pay forward—not for immediate exchanges for public goods, such as education, health care, libraries, and highways, but so we can have them available in the future. Public goods, like education, are not only paid for by taxes from people who need them now or in the near future; they have also been paid for in the past, with taxes that were budgeted then to meet the community’s needs now. When young people have access to educational, mentorship, health, and social service opportunities, they will be better able to contribute to our society’s future and ensure America’s long-term fiscal foundation.

Going forward, we hope there will be many more examples of effective framing to add to our archives on how nonprofits might better communicate about budgets and taxes. We offer our framing tools as a point of departure. If we can agree to keep budgets and taxes at the forefront as we explain how the world works on issues of inequality, human needs, environmental stewardship, and other key societal concerns, we can begin to take back a critical component of what ordinary people need and want to know about exercising their rights as citizens and stakeholders.

NOTES

- See www.frameworksinstitute.org/sfa.html.

- See Shanto Iyengar and Donald R. Kinder, News That Matters: Television and American Opinion (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987); Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, eds., Choices, Values, and Frames (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000); Deborah Tannen, ed., Framing in Discourse (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993); Claudia Strauss, Making Sense of Public Opinion: American Discourses about Immigration and Social Programs (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- Iyengar, “Framing Responsibility for Political Issues: The Case of Poverty,” Political Behavior 12, no. 1 (March 1990): 19–40, www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/586283 .

- See our interactive game tool SWAMPED!, “FrameWorks Issues: Budgets and Taxes,” FrameWorks Institute, www.frameworksinstitute.org/budgetsandtaxes.html.

- Moira O’Neil, “Literature Review and Methods Associated with Cultural Models,” unpublished working paper (FrameWorks Institute, 2007).

- Dorothy Holland and Naomi Quinn, eds., Cultural Models in Language and Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 4.

- See Bradd Shore, Culture in Mind: Cognition, Culture, and the Problem of Meaning (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

- Nathaniel Kendall-Taylor and Susan Nall Bales, Like Mars to Venus: The Separate and Sketchy Worlds of Budgets and Taxes (Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute, 2009).

- Harry J. Holzer and Isabel Sawhill, “Why Won’t Liberals Back Reforms?,” Washington Post (March 10, 2013). (For open access, see www .kansas .com /2013 /03 /12 /2711814 /harry -j -holzer -and -isabel -sawhill .html.)

- Kendall-Taylor and Bales, Like Mars to Venus, 23.

- Kendall-Taylor and Bales, Like Mars to Venus.

- See “FrameWorks Issues: Government,” FrameWorks Institute, www.frameworksinstitute.org/government.html.

- Tannen, “What’s in a Frame? Surface Evidence for Underlying Expectations,” in Framing in Discourse, 21.

- Adam F. Simon, “The Pull of Values,” unpublished working paper (FrameWorks Institute, 2013).

- Simon. “An ounce of prevention: Experimental Research in Strategic Frame Analysis™ to Identify Effective Issue Frames for Public Budgeting and Taxation Systems,” unpublished working paper (FrameWorks Institute, 2010).

- Kendall-Taylor and O’Neil, Having Our Say: Getting Priority, Transparency and Agency into the Public Discourse on Budgets and Taxes (Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute, 2009), 40, frameworksinstitute.org/toolkits/bt/resources/pdf /priority,transparencyandagency-resultsfrompeerdiscourseanalysis.pdf.

- “Fiscal Policy Center: Raising Revenue or Cutting Spending,” Voices for Illinois Children, accessed February 25, 2013, www.voices4kids.org/our-priorities/fiscal-policy-center/raising-taxes-or-cutting-spending/.

- “Support Nonprofits by Protecting the Charitable Deduction and Opposing Arbitrary Budget Cuts,” Colorado Nonprofit Association, accessed March 7, 2013, www.coloradononprofits.org/support-nonprofits-by-protecting-the-charitable-deduction-and-opposing-arbitrary-budget-cuts/.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, National Earned Income Tax Credit Outreach Campaign, Campaign Partner Spotlight, accessed March 7, 2013, http://eitcoutreach.org/category/tax-credit-outreach-campaign-introduction.

- Foundation for Second Chances; “FFSC Mentoring Program Affected by a Recent Government Bill,” blog entry by FFSC, March 6, 2012, accessed March 7, 2013, http://ffscinc.org/ffsc-mentoring-program-affected-by-a-recent-government/.

Susan Nall Bales is founder and president of the FrameWorks Institute, an independent nonprofit research organization founded in 1999 to advance the nonprofit sector’s communications capacity by identifying, translating, and modeling relevant scholarly research for framing the public discourse about social problems. A veteran communications strategist and issues campaigner, she has more than thirty years of experience researching, designing, and implementing campaigns on social issues; Yndia Lorick-Wilmot, PhD, is a trained sociologist in the areas of race, ethnic identity, immigration, and human services, and a senior associate at the Institute for Field Building and Research.