December 15, 2015; Cleveland.com

This past week, Cleveland City Council addressed the ongoing crisis of Cleveland’s failure to follow up on lead-poisoned children. This hearing follows a month-long expose titled “Toxic Neglect” in which the Cleveland Plain Dealer uncovered massive and persistent malfeasance in Cleveland’s Department of Public Health.

“In the past five years, lead poisoning has set at least 10,000 Cleveland area children on a potential path to failure before they’ve even finished kindergarten.

It’s a path that experts say helps to perpetuate two of Cleveland‘s most pressing and bedeviling problems: poor school performance and violence.

The problem isn’t a new one. We’ve known about it for decades.

What we’ve failed to do is fix it. We’ve opted to save thousands of dollars now, and thereby committed to future costs that are likely in the billions. We poison our children, and it’s entirely preventable.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In response to the series and accompanying editorials, Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson fired health department officials and pledged to clean up the mess. According to the Plain Dealer, here’s what the city council learned in a hearing held last week with acting health department director Natoya Walker-Minor:

- Cleveland will hire two new investigators, who will be trained by early 2016, bringing the entire staff to eight persons, each of whom can handle about 100 investigations per year. That is roughly eight percent of the estimated 10,000-case backlog.

- The Department of Building & Housing has been given a list of 230 residences that may be responsible for poisoning as many as 700 children. The was no information presented about whether these units were still occupied and, the Plain Dealer report observes: “Those are just a fraction of thousands of lead poisoning cases referred to the city since 2002.”

- In response to a comment by Council President Kevin Kelley suggesting that this was a “clear the decks” moment, radio station WKSU reported that “Interim city Health Director Natoya Walker [Minor] told council that in many cases the families involved are extremely transient and may move in and out before the child is diagnosed with lead poisoning. Meanwhile, another family moves in before the home is inspected.” After being diagnosed with lead poisoning, should a mother and her baby hang around waiting for the health department to arrive?

- Ms. Walker-Minor further explained that much of the problem resulted from poor record keeping and a failure to coordinate among city departments and the state. “Minor said the Ohio Department of Health and the city have used multiple data systems to track lead poisoning investigations and referrals in the past decade. That has created some confusion. The city is working to get data entered on cases it has and has not investigated that may not be in the current state lead poisoning data system. Some cases could be more than a decade old.”

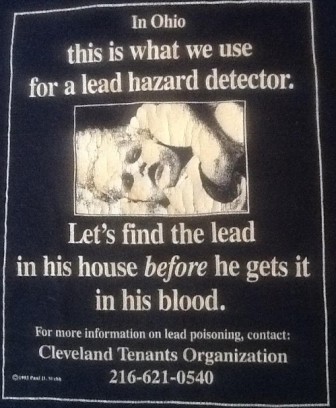

Cleveland’s failure to address this fundamental obligation to its youngest citizens is compounded by the mayor and his administration’s slowly evolving response. The fact of lead-poisoned children and contaminated houses in Cleveland is not news. The story of lead poisoning in Cleveland in no way resembles the Flint, Michigan case where a change in the public water source caused an emergency. Back in the 1980s, advocates were using a T-shirt to illustrate Cleveland’s problem. The shirt had a picture of a baby and the caption, “In Ohio, this is what we use for a lead-hazard detector.” The only thing that has changed is that Cleveland just stopped following up on the findings from the baby lead detectors.

A lack of funding has been a problem. For years, Cleveland depended on federal lead-remediation grants to fuel its Lead Hazard Control Program. Apparently, when that funding source dried up, so did the program. Meanwhile, the city and citizens found funds to build a giant outdoor chandelier in the theater district, grant parking concessions to the nearly winless Cleveland Browns, renew a tax to support sports teams’ playgrounds, and donate money to attract the Republican National Convention (RNC) to town this coming summer. This year comes the good news that several national foundations have provided some funding for lead remediation. But now the mayor is faced with the task of rebuilding the health department’s expertise.

All over the mass media these days, we see reminders of the high cost of doing nothing. High-profile reports have linked the case of Freddie Gray to the problem of childhood lead poisoning. Who knows how lead poisoning may have contributed to the violence that prompted the U.S. Department of Justice to seek a consent decree with Cleveland over the police department’s practice of excessive force?

Add uninvestigated lead-poisoning cases and unremediated lead hazards to Cleveland’s aging housing stock and its problem of childhood poverty. This year, Cleveland ranks second in the country for child poverty according to a report from the National Center for Children in Poverty. A Cleveland Plain Dealer headline says succinctly: “More than half of Cleveland kids live in poverty, and it‘s making them sick.” The connection between poverty and intellectual development is inescapable. But with no functioning public health department, little oversight from state government until the crisis was revealed in the Plain Dealer, and no apparent political urgency to address the problems of lead poisoning and childhood poverty, the immediate future for many of Cleveland’s children seems bleak.

This past week, Congress appropriated $50 million to Cleveland to provide security for the Republican National Convention. It was a hard fight for Ohio’s Republican Senator Rob Portman, but Portman made this a priority. Where were political leaders at all levels during all of those years when poisoning reports went uninvestigated?