July 30, 2019; Governing

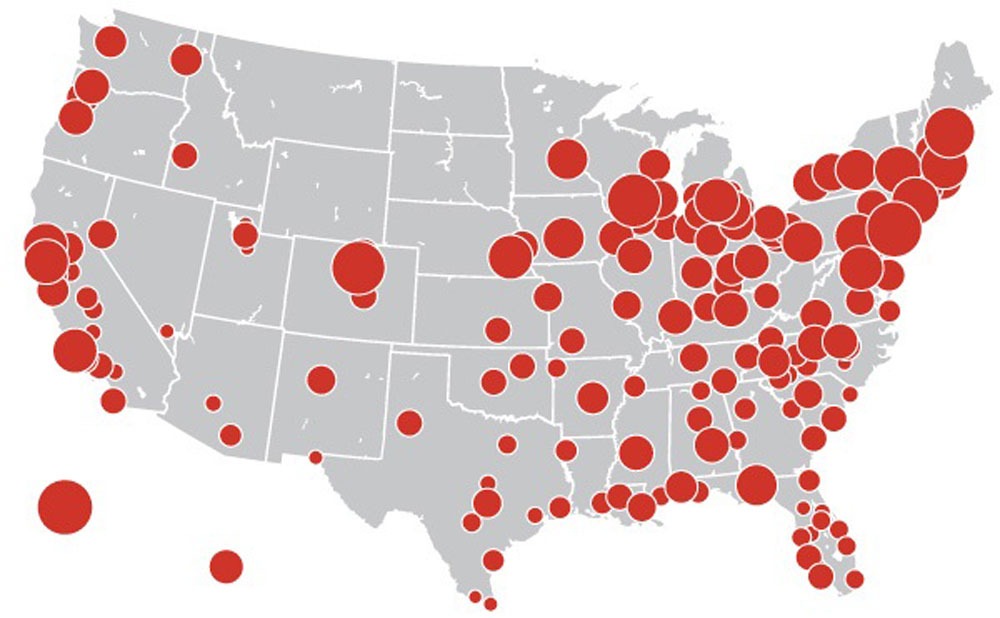

An article in Governing, a publication for people working in the public sector, notes that the distribution of nonprofits across the United States is uneven. This means, among other things, that the ability of nonprofits to extend the work of governments carries far more potential in some locations than others.

To get at the geographic concentrations of nonprofits, Governing used data published by the National Center for Charitable Statistics. It excluded nonprofits with very narrow interests, like scholarship programs, as well as those addressing national interests not specific to that locality. This kind of screening clarifies some natural assumptions that might otherwise be made, especially about larger cities like DC and Boston, with more than their share of the latter.

Among the areas that are nonprofit-rich (even if not all the nonprofits are rich) are “older, more established communities, especially in the Northeast and the industrial Midwest” and capital cities. The article points out that of all US cities, the metro area of Trenton, New Jersey, has more locally focused nonprofits per capita than any metro area with a population exceeding 300,000. Close behind Trenton are Madison and Boulder. Boston leads the pack in larger cities with populations of 1 million or greater, with San Francisco and Washington, DC, coming in second or third.

Though locally focused nonprofits tend to exist in greater numbers in communities with higher rates of poverty, the authors said concentration varies a lot otherwise. “The top 10 metro areas…have more than twice the number of nonprofits per capita as all those in the bottom quarter.” But it is interesting to note what locals believe has produced nonprofit-rich areas. In Madison, for instance, at least one observer says both culture and geography come into play.

The [Madison] metro area has long ranked among the top in the country for its concentration of nonprofits, says Tom Linfield of the Madison Community Foundation. Along with the state capital and the state’s flagship university, there’s a large park system and a cluster of lakes, both of which have numerous nonprofit groups advocating on their behalf. There’s even a virtuous circle of nonprofit activism, Linfield says, with the city’s rich history of foundations and charitable organizations spurring the creation of new grassroots groups focused on individual neighborhoods and specialized issues.

“There are many people just full of passion who feel the need to do something,” he says, “but they don’t want to join [an existing organization]. They want to start their own thing.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

On the other hand, fast-growth cities—like the Las Vegas metro area, the population of which has doubled in the last twenty years—have grown their nonprofit sectors much more slowly than older, established cities. This hold true in Florida, Texas, and Utah.

Again, this article’s interest in nonprofit concentration is based in the degree to which those organizations can pick up the slack of inadequate government services, or where their work complements or augments the role of government but would be inappropriate for government to take on. Sarah Reckhow of Michigan State University, one of the study’s authors, points out that “nonprofits are responsive and can be nimble in adding services when a crisis emerges.”

But does the public link government and nonprofits? It appears they do.

Whether residents actually seek out nonprofits depends on a number of factors. One of them, according to recent research, is their perception of local government. A study by American University researchers found that the more positively citizens felt about their government services, the more likely they were to use nonprofit services as well.

“This all,” concludes the article. “suggests that nonprofits and local governments rely on each other, rather than one sector acting to supplant the other.”

Click here to find your city’s nonprofit concentration.—Ruth McCambridge