May 21, 2020; National Public Radio

Wilkesboro sits atop a low, broad ridge that runs along the south bank of the Yadkin River in the northwest part of North Carolina. Not only does it have, as per its tourism board, “a newly revitalized historic downtown, mind-blowing music talent, stunningly scenic mountain views, heart-pounding outdoor adventures, and Southern small-town charm,” but it hosts MerleFest each year—one of the largest music festivals in the nation, named in memory of the late Merle Watson, son of the great Doc Watson.

In stark contrast, just five minutes down the road from the MerleFest site, sits a chicken processing plant where, last week, 570 of its more than 2,200 workers tested positive for the coronavirus. That’s a quarter of the labor force, though most, according to owner Tyson Foods, didn’t show any symptoms.

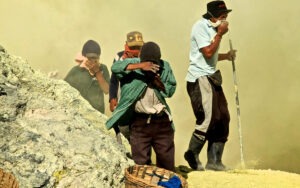

Who works at our nation’s poultry and meat processing plants? Mostly immigrants and refugees, people desperate for a paycheck despite a typical entry wage of $8.50/hour, few prospects for an increase in pay, scant training, and the highest rates of illness and injury of any industry in the nation. Expected to process an average of 2,000 birds an hour, line workers use scissors and saws in tight and slippery quarters, endure air temperatures of less than 50°F, and work on their feet for long periods without bathroom breaks.

Though Tyson Foods, one of the world’s largest chicken, beef, and pork processors, temporarily closed the Wilkesboro plant twice in May for deep cleaning and is “rolling out advanced testing capabilities and enhanced care options on-site to team members,” as well as increasing short-term disability coverage, these measures do not apply to the temporary contract workers who typically make up much of the industry’s work force. Unlike full-time plant employees, these workers, mostly Latinx immigrants, do not receive paid sick leave and can be fired after missing 10 days of work.

Though long a Republican bastion, Wilkes County has a Democratic representative in the state legislature, thanks to the college town of Boone that sits in the same electoral district. Rep. C. Ray Russell found the number of positive test results shocking:

We have yet to hear from them how many deaths and how many people were seriously ill, how many people were hospitalized. Those are the kinds of things they haven’t been forthcoming with.

It’s a question of transparency; I think Tyson owes it not just to Wilkes County, but to the entire region to be more transparent and tell us what they’re doing to make sure their workers are healthy.

And a local hairdresser made headlines after posting a notice on his salon door advising Tyson employees that they wouldn’t be able to get haircuts there until June 8th because of the coronavirus outbreak. But the sign went on to say that after 14 days, all Tyson employees who do come for haircuts will get a $3 or 25 percent discount.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Dueling rural development strategies

The question of how to revive the nation’s flagging rural economies is not an academic one. Indeed, the election of Donald Trump, significantly fueled by rural voters, has brought this issue to national attention.

Wilkesboro is a clear example of a community that has tried two very different strategies to revitalize its local economy, stricken both by the decades-ago shuttering of its furniture and textile plants, and the more recent collapse of the tobacco federal quota and price support system that provided significant cash to the region’s farmers.

The first strategy, sometimes called “smokestack chasing,” involves seeking out businesses and opportunities from elsewhere at any cost and, for many rural communities, translates to snagging a prison, meat processing plant, or casino rather than a Toyota auto plant.

The second strategy, sometimes called “economic gardening,” focuses on building off a rural community’s assets—natural, cultural and historic—and establishing small, sustainable, locally owned businesses. Though it lacks the attendant social and environmental risks of the first strategy, this approach can only deliver a relatively small amount of jobs and tax revenue over a long period of time.

Wilkesboro’s largest employer is now Tyson Foods, where 25 percent of its employees are COVID-19 positive. Wilkes County is now the state’s second-largest supplier of broiler chickens, raised factory-style in row after row of 25,000 square foot houses by contract farmers who “are all but serfs in a feudal system that funnels profits to corporate integrators” like Tyson Foods. The farmers have enormous debt, no control over any of their farming practices, and compete with each other in a “tournament system” that rewards some at the expense of others. Some live below the poverty line.

On the other hand—and using the second economic development approach—Wilkesboro was recently featured in Southern City, a publication of the NC League of Municipalities, for its successful efforts to revitalize its downtown with 26 new businesses opened, concerts in the new Commons, a food truck championship hosted by the Kruger Brothers, 50 nearby wineries and distilleries, and three world-class disc golf courses.

What is the real Wilkesboro, and can it continue to draw tourists and retirees with its new reputation as a COVID hotspot, with North Carolina’s fourth-highest per capita infection rates, trailing Wayne County with its prison and Chatham and Duplin counties with their giant food processing operations? Can these two economic development strategies coexist side-by-side?

“Welcome to Wilkesboro,” says the website. “We’ll take your breath away…” That’s now no longer a metaphor, given COVID’s real presence in this town with two faces.—Debby Warren