Last week, Dan Cantor, the National Director of the Working Families Party, announced that he was stepping down and passing the torch to Maurice Mitchell, a prominent leader in the Movement for Black Lives, the global network behind the Black Lives Matter movement. In an interview with NPQ, Mitchell says,

The response has been overwhelming. There’s been a range of responses, from “Are they really going to allow this to happen?” (“They” being the ubiquitous “they” who prevent black people from doing well.) On the positive side, people see it as a clear signal of hope for the Left that our institutions can change and new institutional leadership can take the mantle. These things can happen.

Mitchell, or as he’s known to friends and colleagues, “Moe,” speaks of something we in the nonprofit sector know too well—the leadership is overwhelmingly white. So, people are taking note of this leadership transition.

Moe shares that it was a long and rigorous process with many talented applicants—and part of that process included his own realization that the Party is a place where his particular skills and experiences would be best utilized.

The Working Families Party was launched 20 years ago in New York by a grassroots coalition of community organizations, union activists, and progressive elected officials. It organizes people to take action; runs bold issue campaigns that raise standards for working families; and recruits, trains, and elects political leaders to local and state offices. It is known for its ability to mobilize, or turn out, voters. Over the past 20 years, it has grown beyond New York and currently has chapters or branches in Colorado, Connecticut, Louisiana, Maryland, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Washington state, and Washington DC. Its issue campaigns include affordable housing, climate change, criminal justice reform, debt-free higher education, elections, fair taxes/fair budgets, great public schools, green economy, healthcare, immigration, LGBTQ, minimum wage, money in politics, racial justice, retirement security—basically, worker rights. Moe says, “By ‘worker,’ we mean anyone who wakes up and puts in work to survive.”

Moe explains that his new role represents an alignment between movements and government. He says,

We’re basically experimenting with aligning movements and outside energy with parties and governing power. The idea is that there could be alignment between outside power and governing power—not to replace or prioritize, but to align. There’s a place for movements to do what they do, and for parties to do what they do.

The Party spent its first 20 years demonstrating that it could successfully create and run a political party based not on the extractive desires of “the One Percent,” or even the rights of the middle-class, but on the needs of working class and poor people. And it has succeeded: “In 2017, almost two-thirds of the 1,036 WFP-backed candidates…endorsed for state and local office across the nation were elected.” And that is no small feat. As Moe says, “In a very narrow two-party system that is skeptical and antagonistic to anything outside of that, it took a lot of work, resources, and organizing to be able to consistently win election cycle after election cycle and issue after issue. So that it can’t be denied that the party strategy is critically important.”

According to Moe, the next 20 years of the Party is about “the expression of a multiracial populist grassroots movement.” He notes that the conservative nature of political parties seeking to preserve their power leads them to cultivate a complacent base that will turn out to vote for them cycle after cycle. But, he says, “What we’re interested in, to be more concrete, is to be a political home for all the young people from Occupy, Movement for Black Lives, the anti-gun-violence movement, the women’s march—the disruptors. Both parties don’t satisfy the needs of working class people.”

He suspects this will be a generational shift; the changes won’t come overnight. But the Party has been at it, winning down-ballot races. “Down-ballot” here means local legislatures, local city councils, and even as far down as school boards. These are elected offices that really matter in day-to-day experience, like public safety, police, housing, and zoning. This is bottom-up politics; the Party seeks to build up from local and state races to someday be able to influence national politics.

A recent report commissioned by Justice Democrats, a political action committee of former Bernie Sanders supporters focused on taking money out of politics, and authored by Data for Progress, a group of young, white Millennials seeking to use data to inform public opinion, suggests this may be a smart strategy. “The Future of the Party” proposes donor-class concerns are derailing the Democratic Party and that, in fact, the party’s base is “united around policies that would create a fair economy for all, racial justice and gender equality.” The report’s key findings include:

- The Democratic base is ready for multi-racial populism. 80 percent support the government taking action to reduce inequality.

- It’s time for a new non-voter revolution. Full turnout would have led to a Democratic presidential victory in 2016.

- Democrats are not representing the progressivism of their constituents. Many elected Democrats reject policies that their districts support.

However, perhaps most significantly in the history of the US, according to the report, “For the first time since it’s been polled, a majority of white Democrats are more likely to blame discrimination than ‘willpower’ for racial inequality.” This change in public opinion is credited to the Black Lives Matter and Dreamer movements.

According to Moe, the Party is taking this report into account, as it aligns with its own field-based experiences. The report compares data from political polling of Democrats (including non-voters) and voting records of elected Democrats and consistently finds significant gaps slanted towards the center. This report asserts that “many Democratic consultants and party leaders are still stuck in the ’80s and ’90s.” Anti-poor and anti-immigrant statements may have worked then, “when many white Democrats held anti-immigrant and anti-black views, but they don’t make sense anymore.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

For example, the data show that “85 percent of Democratic primary voters support some path to citizenship,” and “Democratic primary voters support increases in government spending and overwhelmingly reject cuts to government.”

The report contends that the biggest problem for Democrats is not gerrymandering, but their failure to mobilize the non-voting segment of their base, and this has class and race implications. According to the report, even when Democrats do mobilize their base, “there are deep class divides in reported contact. Among registered Democrats living in a swing state earning under $50,000, 65 percent reported contact, compared to an 80 percent contact rate among Democrats living in a swing state earning more than $100,000.” Further, “Democrats also struggled to mobilize people of color.”

The report points out that academic literature on past expansions of the right to vote— to women, for example—shows that “the political implications of turnout are now well established.” It also notes that political research shows that “when politicians are given accurate polling about their constituents, they move to align with constituents.”

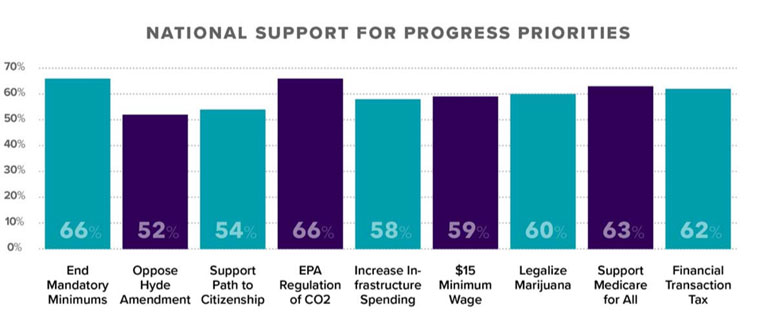

The report cheekily concludes with a list of elected officials who don’t adequately represent the progressive agendas of their constituents and a graph of the issues that are underrepresented by them.

These are the people that the Party serves, and Moe is excited and ready to take it to the next level. He concludes,

One of my main mandates is around growth, because over the next five to 10 years, we want to turn around and see a party that is even more diverse than it is today and made up of activists in their own communities that are self-organizing. I want to turn the Party over to the people, so that anyone that has the desire can build a local presence for the Party. I want to take the lessons I learned from distributive organizing in movements and apply it to party-making. We have great organizers and I want to give them the ball and let them take the lead in their communities.

This is a particular moment in our country’s history. A moment of realignment culturally and politically creates opportunities. It means a party like WFP, although the idea of a party like us may have made sense when it was created, it might have been harder to think of it as available. At this moment, it’s even clearer…as party affiliation is on a downward trajectory, in a moment where the past election has shifted people’s understanding of traditional institutions, there’s potential in this realignment, in this shakeup, for people with principles and strategy and leadership. We can be that leadership if enough of us come together.

While this story highlights the realness of a workers’ party that has decided to turn over its leadership to a leader of the people most impacted, it also celebrates two significant successes of the Black Lives Matter movement: shifting public opinion on the structural causes of racial inequity and developing a global network of skilled and committed activist ready to tackle governance.

The Working Families Party seeks to further grow its political success by organizing for racial justice and the Movement for Black Lives seeks to influence politics. It’s so common sense, it’s crazy.

Moe’s tenure at the Party starts in June. Until then, he will be wrapping things up at Blackbird, the movement organizing nonprofit he cofounded with Mervyn Mercano and Thenjiwe Tameika McHarris. He anticipates launching his work at the Party with a national listening tour and encourages NPQ readers to give to the Working Families Party, join a local chapter or branch, or start one.

Disclosure: The author worked with Moe Mitchell in the Citizen Action network and as a consultant with the Movement for Black Lives.