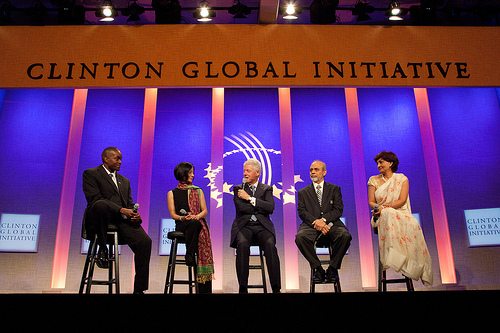

Taylor Davidson / Clinton Global Initiative

One thing that was obvious about the Clinton Global Initiative (CGI) annual confab in New York City last week is that former president Bill Clinton really knows how to pull in the financial commitments from corporate and philanthropic players. Whether you liked or disliked Clinton’s performance while in office, there’s no question that he has mastered the art of harnessing private-sector muscle—in the form of dollars, publicity, credibility—behind CGI priorities.

Part of it is Clinton’s ability to confidently weigh in on nearly any aspect of humanitarian or economic policy while showing that he understands where all the various interest groups on a given issue are coming from. Last week in the online publication UN Dispatch, blogger Penelope Chester noted, “Those who have been following President Clinton and have had a chance to hear him speak before know that he has an uncanny ability to speak authoritatively about essentially any subject under the sun.” For example, during a CGI roundtable with bloggers, Clinton expounded on a constellation of issues:

- Haiti: “It’s a tough world out there, and the international community has not given all the money it promised to give. When there was a political slowdown occasioned by the last election and its aftermath, it in effect operated as an excuse for donors not to pony up. But if we get more donor money this year and we keep the economics going right—and we’ve got a lot of interest—I think it’s going to be really good.” He added later, “We’ve got a shot . . . but we need more money.”

- Climate Change and Refugees: “I think that you have to assume that because of climate change, there are going be a lot more refugees . . . and that the laws which exist, and the systems of support that exist, not just the U.S. but elsewhere, were basically built for a different time when you might have a surge of refugees from this country or a surge from that country, because of a particular political upheaval or a particular natural disaster. And that’s almost certainly going to not work now.”

- Israel and Palestine: “The two great tragedies in modern Middle Eastern politics, which make you wonder if God wants Middle East peace or not, were Rabin’s assassination and Sharon’s stroke. . . . The Israelis always wanted two things that once it turned out they had, it didn’t seem so appealing to Mr. Netanyahu. . . . Now that they have those things [a credible Palestinian government on the West Bank and efforts by its neighbors such as Saudi Arabia to work toward normalization of relations with Israel], they don’t seem so important to this current Israeli government.”

- Cutting the Deficit: “I personally don’t believe we ought to be raising taxes or cutting spending until we get this economy off the ground. If we cut government spending, which I normally would be very inclined to do when the deficit’s this big, with interest rates already near zero, you can’t get the benefits out of it. . . . [W]hat I’d like to see them do is come up with a bipartisan approach, starting with the payroll tax cuts because they have the biggest return.”

- Tea-Party Politics: “You can stand up and say anything and nobody rings a bell if the facts are wrong. There’s no bell ringing. It’s crazy, we’re living in a time when it’s more important than ever to know things. And not just to know facts but to put them in a coherent, sensible pattern. And we live in a time, if you just want to talk about the economy, where the model that works for economic growth and prosperity is cooperation. But the model that works in politics is conflict. . . . You know, there’s not a single solitary example on the planet, not one, of a country that is successful because the economy has triumphed over the government and choked it off and driven the tax rates to zero, driven the regulations to nonexistent and abolished all government programs, except for defense, so people in my income group never have to pay a nickel to see a cow jump over the moon. There is no example of a successful country that looks like that.”

- “Dancing with the Stars”: “This is interesting—actually they contacted me once about [appearing on the show]. . . . And I told them I didn’t have the time to train for it. You know, you actually go out there and train—you really work at it. . . . Hillary said to me, ‘You know, when I’m not secretary of state anymore, we should go take dancing lessons.’ So we’ll start with the tango.”

The former president’s remarks at the CGI bloggers’ roundtable will sound familiar to anyone who has seen first-hand a Bill Clinton performance during his tenure as POTUS. I was there to witness his stunning no-notes introductory remarks at the first and only White House Conference on Philanthropy in 1999, where he made donors and foundations squirm by calling for higher levels of charitable giving by the rich and, as a corollary, higher foundation payout rates. The kind of commentary he delivered at the CGI conference is representative of his remarkable genius: an ability to call on and integrate knowledge from different realms of intellectual thought and analysis. Whether or not you liked his policies as president or could forgive his personal failings, there’s no question about the quality of Bill Clinton’s mind.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Can Clinton’s masterful performance at the 2011 CGI tell us anything about nonprofits and philanthropy? Chester of UN Dispatch reported that this year’s CGI garnered 194 commitments valued at $6.5 billion. Is that all due to the fact that he used to occupy the Oval Office? That can’t be the whole story, because he left office dogged by scandals and misadventures. Is it because his wife Hillary happens to be the U.S. Secretary of State? (In response to a question about the 2012 and 2016 presidential elections, Clinton described her as “the ablest person in my generation.”) Maybe, but her senior role in the Obama Administration probably works both for and against her, with some potential donors eager to play up to a very powerful cabinet officer, while others perhaps steer clear of her due to their opposition to Obama policies at home or abroad.

Let’s go out on a limb and suggest some additional factors behind Bill Clinton’s brilliance in generating philanthropic commitments from all sorts of people and corporations (notwithstanding some real problems with expenditures, which we have documented here). These are attributes that all nonprofits would do well to emulate:

- Bill Clinton knows what he is talking about. This is not a guy who needs to read from the teleprompter or have aides whisper answers in his ear or who struggles to recall canned lines that he learned in rehearsals in order to avoid gaffes. It takes more to inspire confidence in donors of all sorts than simply not being a dunderhead. To get a financial commitment, it is a big help when the asker is legitimately on top of the issues and avoids puffy rhetoric.

- Bill Clinton doesn’t shy away from the big ask. Just as he displayed during his Philanthropy Conference pitch back in 1999, he isn’t afraid to tell potential CGI donors to boost the percentage of profits donated or to raise their endowment payouts. One can imagine him looking at individual, corporate, and foundation donors and, without suffering dry mouth or nervous shakes, calmly adding a zero at the end of the dollar amount they had planned on donating.

- Bill Clinton looks to a wide variety of donors. It’s not simply that he is (or was) a moderate Democrat able to work with conservatives and liberals; he truly seems to believe—and conveys that belief strongly—that everyone of all political hues and stripes ought to be able to find something within CGI to meet their charitable or philanthropic urges. This year, CGI commitments include Procter & Gamble’s initiative on safe drinking water for children in Africa, ONE’s response to the famine on the Horn of Africa, Deutsche Bank’s pledge to New York City’s Energy Efficiency Corporation, World Vision’s focus on “Girls, Women, and Water,” and a wide variety of others.

The post-White-House Bill Clinton is hardly perfect, even as a philanthropist. (Two examples: the reluctance of the Clinton Library Foundation to reveal major donors during Hillary’s presidential campaign and the criticism leveled at some of the Clinton Foundation’s work and partners in Haiti relief and reconstruction activities.) Regardless, with all his flaws, Clinton still has much to teach the sector about how to mobilize private capital for humanitarian and anti-poverty purposes.