We have just come through a wrenching economic downturn. Those on Wall Street seem to have largely recovered. Many on Main Street seem to be on their way. Some, however, are still in dire straits. Among the most dramatically hit are young urban adults emerging from economically challenged households without the advantage of a college education. While the headline rate of unemployment has fallen from its October 2009 peak, for young adults between the ages of sixteen and nineteen unemployment has remained around 25 percent throughout the alleged recovery.1 For young adults in inner cities, particularly individuals of color, the story is worse. In fact, their chances of finding durable, skills-based employment are below their chances of being incarcerated.

In 2000, an organization was founded in Boston to address this very issue. Year Up is a one-year intensive training program that provides urban youth with professional skills, college credits, and corporate internships. Year Up has proven to be an effective program, and the formerly Boston-focused operation that once served a couple of hundred local kids a year now serves nine communities. It is growing rapidly and with fidelity, and employs a model that sustainably funds operations without dependency on major grant funding. This year, more than 1,300 students will participate in this program. If past performance is indicative, nearly 1,100 of them will likely wind up either with permanent, full-time technical jobs or enrolled in college. How Year Up grew from a local program for at-risk Bostonians to a national solution to a chronic problem is, at least in part, a story of Philanthropic Equity.

What Is Philanthropic Equity, and Why Does It Matter?

Philanthropic Equity is an emerging practice whereby a nonprofit raises grant money to play the role that equity financing would normally play in a for-profit organization. Philanthropic Equity acts as an early-stage investment in an organization, paying the bills while waiting for the business model to kick in.

Unlike for-profit equity investors, Philanthropic Equity investors seek social rather than financial returns, and grants are invested to provide a one-time infusion of capital. And investors have the expectation that the recipient will use that capital to further its business model (rather than to serve its constituents).

How does Philanthropic Equity differ from any other grant? For virtually any nonprofit, there is a revenue “bar”—the amount of money the organization needs to bring in to pay for operations. Philanthropic Equity doesn’t help an organization hit that bar. Instead, it raises the bar.

Ordinary revenue, as associated with an organization’s business model, is money received to deliver the service (or product) a nonprofit provides. It represents a payment to the organization by someone who cares, and can take many forms—a pledge to a local public radio station, federal funds for neighborhood stabilization, a foundation grant to provide services to homeless families, proceeds from the sale of Girl Scout cookies—but in all cases it represents the funding integral to the business model of the nonprofit. These types of ordinary revenue are also known as “buy money,” in that they “buy” the programs and services that nonprofits deliver to the clients they serve. Sustainability is having sufficient buy money to cover the full costs of doing business on an ongoing basis.2 The amount of buy money an organization needs each year sets the bar. Every dollar it raises or earns helps to meet that bar. The height of the bar is the full cost of conducting the business for the year.

For Year Up, this buy money comprises government funding for jobs programs, locally raised contributions, and funds from the businesses that employ the interns that come out of the program. This business model can pay for a program on a local scale, but just barely. And these types of revenues can never be sufficient to expand the program into new cities, pay for start-up costs, or create the sort of infrastructure required to manage a national operation. This is where Philanthropic Equity comes in.

Philanthropic Equity is expressly not buy money. It is part of a second category of money that can be characterized as “build money.” Build money builds the enterprise from which buyers buy services. By raising build money, a nonprofit creates the expectation that it will build, which almost always requires increasing the amount of buy money it generates each year. Build money raises the revenue bar.3

Raising the Revenue Bar

So why would a nonprofit manager want to raise this “bar-raising” money? Often, the scale of a nonprofit is not up to the scale of the problem it seeks to address;? sometimes an organization’s business model only works when it reaches a certain scope or scale;? sometimes a new business model would be more appropriate, and the transition cannot be funded by the proceeds of the existing model;? and sometimes it is simply hubris. But whatever the case may be, there are certain freedoms that come with raising both the bar and the money to help reach it. And Philanthropic Equity, in particular, plays an important role in circumstances where other forms of build money cannot deliver the desired transformation. For instance:

Long-term investments: Nonprofit organizations are often reticent to make long-term investments in their capacity. Oft-deferred investments include such things as developing a modern, integrated IT system, hiring a CFO appropriate to oversee the organization they seek to be, hiring fundraisers not likely to pay dividends for a year or two, or developing a modern, sophisticated brand. Each of these requires that the organization’s leaders have confidence in the financial strength to pay for them over time. By pre-raising the capital for transformation (Philanthropic Equity), such investments can be undertaken with confidence.

Trial and error: Edison tried over 1,000 ways to make a light bulb. Had he been funded $2,000 by a foundation to make 1,000 light bulbs ($2 foundation dollars per bulb), he would have made 1,000 quick-to-burn-out bulbs with the available technology. By exhaustive experimentation, however, he discovered a combination of filament and design that changed the world. Whether trying to invent a new service model or exploring new business models, we would be well served if nonprofits were able to experiment more. Most grants are so restrictive that they leave little or no room to experiment.

Focus on execution: Building businesses is hard. When executive directors are required to continually fundraise to close the year’s budget (or worse, meet the month’s payroll), they are unable to focus on the critical challenges of building and running the operations. Abraham Lincoln said that if given six hours to chop down a tree, he’d spend the first four sharpening his axe. Nobody would spend the first four hours raising money to buy a dull axe, but that is exactly what many social entrepreneurs do. Philanthropic Equity allows them to both sharpen their organizational axes and get to work chopping.

Simplifying funder relations: By aligning a group of funders’ support with a common plan, shared expectations, consolidated financial output, and outcome reporting, the time and expense of interacting with those funders is greatly reduced.

In the case of our exemplar, Year Up, build money was needed to pay the one-time expansion costs, fund the first few years of each new region’s operations until they reached sustainable scale, and invest in the talent and systems required to run a national operation. The hope was that after expansion, the regional sites would be self-sufficient and provide a small amount of money to fund ongoing support from the home office. They are unlikely ever to be sufficiently prosperous to repay the start-up funding, and requiring them to do so would both cast an unhelpful burden on them and create a story not conducive to their ongoing fundraising needs. For these reasons, Year Up raised $19.3 million in Philanthropic Equity to fund their expansion costs.

Does Philanthropic Equity Work?

The appeal of Philanthropic Equity notwithstanding, we should ask whether it works. Does raising and deploying large amounts of growth capital in this manner transform organizations into more effective service deliverers? While early evidence suggests that it does, like so many questions concerning philanthropic efficacy this is hard to answer with certainty.

For most grants, an organization is expected to deliver a specific set of services, or spend money in a particular way, or invest in building very specific capacity. Answering the question of whether an organization has done so is fairly straightforward. Having concrete objectives and completing those objectives during the term of the grant make for generally measurable results. In the case of Philanthropic Equity, however, the funds are substantially unrestricted, and the desired result is a sustainable organization supported by other revenue over long periods of time, making results rather harder to measure.4

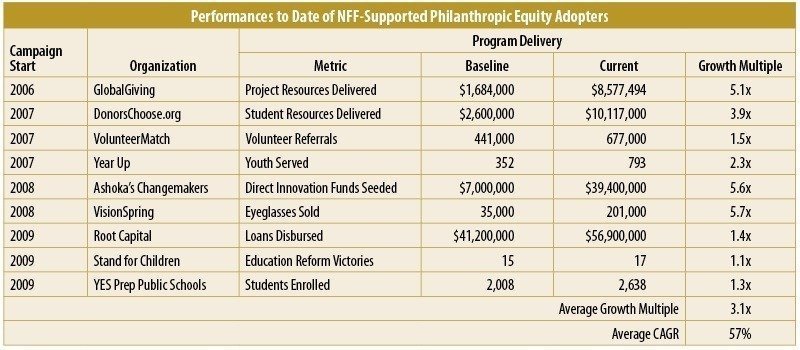

Nonprofit Finance Fund (NFF) Capital Partners has been working since 2006 with a small number of organizations to raise and deploy formal Philanthropic Equity, and they have tracked their results (see table, above). While these organizations do not represent the entire universe of Philanthropic Equity, they are probably the most clearly defined group using the methodology. In our last annual survey of their results, we found remarkable outcomes since the application of Philanthropic Equity:5

- 57 percent average annual growth of each organization’s primary program delivery metric;

- 36 percent average annual growth of business-model revenue (which excludes Philanthropic Equity);

- 100 percent of participating organizations expansion of both service and business model revenue.

These results are even more remarkable when seen in the context of the broader environment. The time frame of the analysis (2006–2009) spans the most dramatic economic downturn in our careers. During this period, 30 percent of all nonprofits reported declining revenue, and 98 percent reported growth below their mean.6 Also worth noting is that these are early days—none of the nine organizations in our cohort has completed its growth plan or depleted its growth capital.

Will they all reach sustainability and deliver on the promise? Probably not. But no venture capitalist would expect all investments to pan out as planned—in fact, only a small minority typically do. Philanthropic Equity is about making sizable bets on plans and teams whose success is uncertain. As it turns out, better than half of this cohort are tracking very well against their respective plans, with six of the nine having a higher level of sustainability than at the beginning of the period; the other three had a drop in their sustainability. As most of the nine had planned for an interim dip, however, even for those three this may not necessarily be a sign of weakness.

Anecdotally, other Philanthropic Equity investments seem to be delivering similarly well. Citizen Schools (see below) is one of three organizations in a cohort that the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation (EMCF) calls the Growth Capital Aggregation Pilot. While these three organizations’ funding relationships, terms, and grant structures are distinct, their investments bear hallmarks of Philanthropic Equity. As with the NFF group, these organizations are, according to their recent reporting, transforming themselves to great effect.7 The other notable success story is the $60 million of early-expansion capital Wendy Kopp raised for Teach For America. There are likely other examples, both of success and failure, of which we are not yet aware.

Adoption Challenges

So, if Philanthropic Equity is so promising, why isn’t it being adopted everywhere? There are four primary challenges to building support for Philanthropic Equity among grantmakers:

Orthogonal strategic and tactical demands. Giving away money turns out to be complicated. Most grantmakers are extraordinarily attentive to a handful of dimensions of their grantmaking and have thus far shown little appetite for adding yet another. They each focus on a subset of an organization’s theory of change, its size or stage of growth, its geographic footprint, participation in various groups, etc. Then, they layer on their internal considerations (timing, payout, precedent setting, etc.). Thinking through the question of which grants are about buying and which are about building seldom trumps (or rises to the level of) these other issues as a priority for program officers, foundation presidents, or their boards. And so it will remain until the transformative potential of Philanthropic Equity investments ignites grantmakers’ imaginations as a tool for closing the gap between “What are we trying to do with our grants?” and “What are we trying to accomplish in our community?”

Comfort with the norm. Ingrained habits are persistent. Grantmakers and grantees have developed a sort of muscle memory around their cycles of giving and asking. In the high-stakes realm of a primary funder relationship, grantees are reticent to upset the applecart. Grantees have learned to speak the language their program officers want to hear about the transformative impact of their grants. It is an effective fundraising approach to cast an organization’s program as a critical cog in the strategy of each funder, encouraging funders to think of the organization as an extension of their strategy. Philanthropic Equity turns the tables, putting the operating nonprofit in the center of the solution and asking funders to align in support of a single strategy. One can readily imagine how reticent an executive director might be to ask a large potential funder to come along on this shift; it is far easier to dance the dance that has worked in the past.

Aversion to collaboration. Collaboration is hard. Effective Philanthropic Equity requires investments on a scale individual funders are seldom equipped (or willing) to provide. Most foundations are unaccustomed to relying on other funders’ participation for achieving success.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

George Overholser of Third Sector Capital Partners describes what is required to solve these second and third challenges as a “Copernican shift,” whereby funders cease to be the center of the system, instead coalescing around a well-anchored program. The consequences for the grantor–grantee relationship are challenging enough; the perhaps less-obvious consequence is that among funders. This shift becomes powerful only when multiple funders align their support toward common ends. This sort of collaboration is yet another challenge for the adoption of Philanthropic Equity. At the very least, the collaboration can be uncomfortable—going through the process of discovering with whom to collaborate, assessing the collective needs and objectives, and reconciling the various timelines is a potential nightmare. With so many other pressures, the payoff would need to be both obvious and substantial.

Inappropriate accountability tools. Accountability conventions run contrary to Philanthropic Equity. The current standard of funder accountability requires regular reporting of the outputs of individual grants, with ongoing support contingent upon those results. Philanthropic Equity requires a commitment in anticipation of results over much longer time horizons, and with much different measurability. Foundation professionals are under considerable pressure to ensure their grants’ effectiveness. In attempting to do so, conventions for grant accountability have arisen, including highly restrictive grant conditions, performance-tracking regimes (often wishfully described as outcome tracking), and processes for making further support dependent upon initial results. While any of these conditions might be well intended, they are incompatible with the notion of providing a team and a plan with flexible, committed resources required to foster success. In the for-profit analog, equity funds are provided irrevocably for “general corporate purposes” and in very large rounds of financing. Venture capitalists know they cannot hedge their risks by overly constraining or managing investments once they have decided in whom to invest. Foundations frequently attempt to do just that.

The Future of Philanthropic Equity

What would it take to overcome these challenges and for Philanthropic Equity to really take off? The short answer is, we don’t know. In 2006, as we were laying out the objectives for NFF Capital Partners, we set a goal of witnessing $300 million in Philanthropic Equity investments. We thought such a volume would create an array of success stories that would induce the field to take off with a life of its own. At the time of this article, we have seen more than $340 million, and yet no unstoppable movement is in sight.

Along the way we have also learned a fair bit about how hard all of this is. For all participants, Philanthropic Equity is a high-stakes endeavor. Even now, after several hundred investments have been made in a dozen and a half deals, each feels like a one-off experiment. The vast majority of funders require specific support to participate. Terms are becoming more standard for the deals NFF supports, but still require tailoring to each situation. Measurement and comparison are complicated and challenging.

Perhaps most surprising, only a very few funders have become actively engaged in working out the process challenges of Philanthropic Equity investments. Similarly, with the exception of the EMCF-led Growth Capital Aggregation Pilot, investments have been coordinated by the recipients rather than by a syndicate-leading foundation. Widespread adoption will require that a collection of funders periodically play leading roles, and that more formal syndicates become the norm.

To the extent that a consensus is building around Philanthropic Equity practices, those practices reside with only a small cadre of practitioners. Perhaps the best potential for easing the process and standardizing the practice lies with the adoption of appropriate reporting standards. Today, GAAP accounting standards for nonprofit organizations do not provide for measurement of equity investments. Tools have been created to work around those constraints, and they are successful. They are not, however, uniform. For real transparency and comparison between applications, common standards are required. These should not be expected to emerge organically; regulatory support is required. Imagine how much less resistant foundations and the nonprofits they support would be were they able to rely on standards from FASB and guidance from the IRS about how to handle such investments.

What would a vigorous market in Philanthropic Equity look like? Would all grants become build-money investments? Absolutely not. In all of the examples we’ve seen, the total need for equity investments is small relative to the ongoing buy money each organization needs. Given the desire for organizations to be sustainable after the investments are consumed, it could hardly be otherwise. Further, many nonprofits do not have significant need for equity investments—either they are not seeking significant transformation, or the economics of their plans do not require significant capital beyond their own means. Of those that do, a significant portion have economics so predictable and strong that debt is an easier path to funding. If only 1 percent of the funds currently flowing to U.S. nonprofit organizations were in the form of Philanthropic Equity, it would be sufficient to radically alter the growth trajectories of many of the highest-potential organizations in the social sector.

What impact might that change have? Asking that now is perhaps akin to asking Wilbur Wright what impact the now ubiquitous jet-powered flight might have. He couldn’t possibly have known, but it’s fairly certain he thought it was worth finding out.

As for Year Up—having used up most of their $19.3 million in Philanthropic Equity, they now have active programs in nine cities. Sustainability on business-model revenue is near, although the economic environment has been less than helpful. Demand for the program is stronger than ever. Did Philanthropic Equity help? At the time of this article, Year Up was well under way, with a $55 million campaign to fund further expansion and program improvement. Among the anticipated funders are several participants from the first campaign. Having both Year Up and their equity funders choose to double down is about the strongest endorsement I can imagine.

Notes

1. Bureau of Labor Statistics (www.bls.gov), September 2, 2011.

2. Note that buy money includes both earned and contributed revenue. The distinction between the two, while important to accountants, is unimportant to our characterization of buy money, or its counterpart, build money.

3. Other types of build money include more conventional forms that anticipate repayment of the funds somewhere down the road. These are financial-return-seeking investments. Debt is in this category, as are recoverable grants—esoteric instruments intended to behave like for-profit equity, deferred compensation of staff, and, in some dire circumstances, receivables factoring.

4. Among the prerequisites for the propagation of Philanthropic Equity is the practice of systematically measuring results. NFF conducted a study monitoring the progress of its clients adopting formal Philanthropic Equity treatment (called the SEGUE methodology). The study does not purport to provide a comprehensive view of all Philanthropic Equity currently deployed in the field. Such a comprehensive view would require both widely accepted standards and an impartial third party to monitor progress. At this point, both accepted standards and an impartial monitor enjoy a high ratio of talk to action.

5. NFF Capital Partners 2010 Portfolio Performance Report (http://nonprofitfinancefund.org/capital-services/portfolio-performance-report) reports on the progress of nine Philanthropic Equity users for whom multiyear data are available. Results represent the mean of data collected from these organizations.

6. Based on an NFF analysis of GuideStar 990 data.

7. The Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, “Growth Capital Aggregation Pilot,” http://www.emcf.org/how-we-work/growth-capital-aggregation-pilot/

Craig C. Reigel is the managing director of Nonprofit Finance Fund (NFF) Capital Partners.

VolunteerMatch.org: The Promise of Compelling Social Returns

VolunteerMatch (VM), an early adopter of Philanthropic Equity, operates an eBay-style online database of volunteer opportunities. Individuals log on and search for meaningful ways to pitch in, looking in their communities, in their field of interest, or for ways to use specific skills they possess. Like all marketplaces, the value increases as the number of participants on both sides grows.

VM is also a social enterprise, supporting itself with a combination of fees from corporate participants seeking access to the volunteer opportunities, fees from nonprofits seeking add-on tools for managing volunteering, individual and corporate contributions, and programmatic grants supporting specific aspects of their work. In 2007, these revenue streams collectively funded 58 percent of VM’s expenses.

In 2007 VM began a $10 million campaign to fund the expansion and improvement of its volunteer database and associated services. VM’s plan sought to both improve the general user’s experience and provide tools required to increase the participation by fees-paying corporate and nonprofit customers. The promise was that by the end of investing the campaign proceeds, the business-model revenues would support 100 percent of the enterprise. In March 2011, VM reported that business-model revenues covered 99 percent of expenses in the prior quarter, and the organization continues its path toward sustainability.

How has the investment done? Like all social investments, that is in the eye of the investor. What is clear is that VM is becoming an enduring institution. VM reports that in 2009 over $472 million worth of volunteer services were arranged via VM’s service—$178 million more than before the campaign launched. Any way you choose to calculate SROI, that’s impressive.

Citizen Schools: Syndication in Action

Citizen Schools has long been a grantee of the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation. In 2007, EMCF organized a coalition of funders including ArcLight Capital, The Atlantic Philanthropies, Bank of America Charitable Foundation, Josh & Anita Bekenstein, John S. and James L Knight Foundation, Koogle Foundation, The Lovett-Woodsum Foundation, The Picower Foundation, Samberg Family Foundation, Skoll Foundation, and the Citizen Schools Board of Directors to collectively fund Citizen Schools’ $30 million growth plan. This program is one of three such collaborations EMCF calls the Growth Capital Aggregation Pilot (GCAP).

Defining characteristics of the GCAP are: (1) upfront, unrestricted funding;?(2) support for a business plan designed to provide sustainability after the end of the grants;?(3) common terms and conditions;?(4) shared approach to performance measurement;?and (5) transparency and shared learning.

Why the grand coalition? As EMCF reports, “Successful grantees require more support than EMCF alone could provide if they were to solve at sufficient scale some of the nation’s most intractable social problems.” By 2012, Citizen Schools plans to annually serve over 6,700 middle-school students from low-income communities, bringing volunteers’ real-world experiences into their classroom.