August 28, 2012; Source: Forbes

Has the “one laptop per child” (OLPC) initiative in Peru flopped? Writing for Forbes, Michael Horn thinks so, and he cites a story in eSchool News to attest to the project’s failure. He says that the eSchool News article suggests that the initiative may have even widened the gap between richer and poorer students in the Andean nation.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

We looked at the original eSchool News article (from early July), which doesn’t quite say “flop,” suggesting more of a “mixed grade” on the laptop initiative, but the content reads like the program largely failed in Peru. Citing independent observation as well as a review of the OLPC initiative conducted by the InterAmerican Development Bank, the eSchool News article cited numerous missteps in the Peruvian implementation of the program, including ill-trained teachers who didn’t understand how to use the laptops (many teachers had never even booted up a computer). The article also notes that the OLPC foundation that provided the laptops was never able to make them available for the intended price of $100 apiece, less than one percent of the schools had Internet access, many schools wouldn’t let the kids take the computers home, and some schools didn’t have enough regular electricity to power the machines. Access to the Internet and the ability of kids to take the laptops home were key components of the OLPC model that Peru somehow forget to follow. According to the article, a lot of the use of the laptops ended up being recreational and social (for games and networking) rather than educational, resulting in no increased language or math skills.

Horn calls the disappointing OLPC results in Peru entirely predictable. The belief in the ability of technology to transform education, he writes, is faulty. He cites the $60 billion spent in the U.S. to equip classrooms with computers, which he says lacks evidence of significant gains among the school system users. His point is that technology itself doesn’t really change much if the underlying structure of education isn’t altered. Horn suggests that in the U.S., the education establishment has tried to jam technology into existing pedagogical models rather than “fundamentally transform(ing) that model into a student-centric one.”

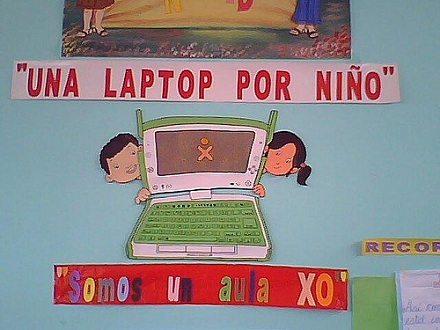

It shouldn’t be a surprise that the organization behind the Peruvian initiative, One Laptop Per Child, suggests a more positive story, framing its coverage as, “Peru: Learning How to Learn.” OLPC writes, “Peru’s education system is built in part on project-based learning. When they decided to introduce OLPC across the country and digitize their classrooms, the Education Ministry developed dozens of longer projects and activities that could be done with nothing but an XO [laptop]. In the most rural areas, schools often meet only a few days a week. Most learning takes place among the children, or with their parents, many of whom are not literate. Half of the over 500,000 students in OLPC Peru live in rural areas. They are exploring new ways to make laptops an engaging part of life and education, including in the traditional classroom. These young students are learning how to read and type in Spanish, which for many is their second language.” The XO laptop features 1 GB of RAM, 4 GB of flash storage (upgradable to 35 GB), no hard drive (to prevent crashes), and is designed to be physically rugged. An updated XO (the XO-3) features a flexible, durable plastic tablet screen.

Founded by MIT Media Laboratory co-founder Nicholas Negroponte, One Laptop Per Child has generated lots of discussion among nonprofits and technology advocates, particularly in the developing world. Compared to so many of the social enterprises that pop up and disappear along with the off-the-cuff ideas of their entrepreneurial founders, OLPC really is the epitome of a social enterprise. But is Horn right that the OLPC model as applied in Peru is so technology-centric that it underplays the importance of training the teachers who will use the XO laptop technology? –Rick Cohen