October 18, 2013; The Daily Iowan

If you think that structural racism is a societal issue, evidence could be found in this report from Iowa. According to Adrien Wing, the executive director of the University of Iowa Center for Human Rights, as described in the Daily Iowan’s coverage of Wing’s presentation at a conference, “Iowa incarcerates African Americans at the most disproportionate rate in the nation.” She said that the African-Americans are incarcerated at a rate of 5.6 to 1 compared to whites, but in Iowa, the ratio 13.6 to 1.

Juan Santiago, a police officer from an Iowa City suburb, described the problem as a “cultural disability” on the part of the police and other authorities—”the criminal-justice field’s lack…[of] a sense of circumstantial understanding for many African American individuals.”

“We don’t truly understand the different cultures that we are trying to help,” Santiago added.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Another panelist at the conference mentioned the common stigma in Iowa that blacks come to the state from the South Side of Chicago.

The challenge with an analysis of structural racism is determining what nonprofits might do about it. At the conference, Phillip Coleman, the outreach coordinator of Urban Dreams, a human services nonprofit in Des Moines, called for training police to “deal with minorities,” apparently addressing the “cultural disability” problem that Officer Santiago cited. However, the Daily Iowan report didn’t go very deep into potential actions or solutions.

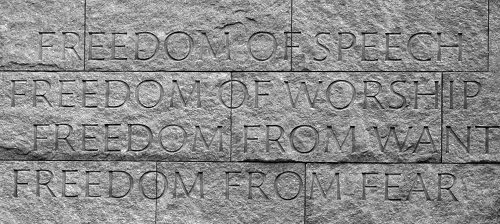

It so often appears that structural racism is better studied than acted upon. For a definition of structural racism, a workshop held for Grantmakers in the Arts offered this definition from the Center for Social Inclusion (CSI):

“It is the blind interaction between institutions, policies, and practices that inevitably perpetuates barriers to opportunities and racial disparities. Conscious and unconscious racism continue to exist in our society. But structural racism feeds on the unconscious. Public and private institutions and individuals each build a wall. They do not necessarily build the wall to hurt people of color, but one wall is joined by another until they construct a labyrinth from which few can escape.”

“Structural racism is the silent opportunity killer,” according to CSI. A project called Iowa’s Opportunity Gap—a collaborative effort of IowaWatch, the Gazette (Cedar Rapids), other Iowa press outlets, and the Colorado-based I-News—last month documented “the gaps in education, income and housing among whites, blacks and Latinos in Iowa have grown worse over the last five decades.” The solutions in the series, however, often felt like they were calls for better understanding and appreciation among racial groups, sometimes confronting overt, conscious racial discrimination (such as landlords’ rejections of Section 8 vouchers) rather than the less overt or even unconscious racism that undergirds the issues described in the conference and in the Gazette/IowaWatch series.

One of the IowaWatch articles called for groups such as the Calvary Family Center and Athletes for Education and Services that “focus on youths…[to try] to develop attitudes that arm a new generation of problem solvers“ to address Iowa’s worsening opportunity gaps. Trying to inculcate mutual understanding among racial groups is fine, but if the issues are hidden beneath the surface, unconscious, or sometimes even intended benevolently, then the solutions require something different, strategically targeted, and aimed at overcoming the unconscious barriers, as opposed to policies of overt discrimination.—Rick Cohen