December 21, 2013; Chicago Tribune

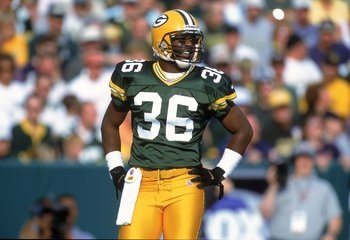

Last month, on the heels of a reported IRS investigation, a federal grand jury opened a criminal review of a charity founded by former Green Bay Packer star Leroy Butler. Federal grand juries digging into charities are kind of rare, especially when sports celebrities are involved. Among the allegations about Butler’s charity are its submission of only one tax return in over a decade of existence, Butler’s purported acceptance of personal appearance fees as high as $10,000 for showing up at his own charity’s events, and claims of potential misuse of money raised at a charity golf tournament.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Since the grand jury proceedings are secret, there’s no information available to NPQ about what might be in store for Butler, although some of the “OMG, we had no idea” comments of people and firms associated with Butler and his charity aren’t particularly compelling. But problems of charitable accountability among charities established by sports stars are not new and seem to persist despite periodic press scrutiny.

Jared Hopkins has a long story in the Chicago Tribune describing the problems of a number of charities associated with sports stars associated with Chicago pro teams. Among the charities Hopkins describes are those of former Bear Jerry Azumah, which raises money despite being out of compliance with federal and state authorities, former Bear Tommie Harris, who shut down his charity after it lost track of a large amount of money, former Bear Chris Zorich, who had to pay $350,000 to state authorities for missing funds, former Bear J.T. Thomas, who closed his charity when it proved too much for his mother to run, and former Cub Alfonso Soriano, which seems abandoned and whose website contains advertisements for adult websites.

What Hopkins didn’t focus on is how these charities get established. In most cases, the athletes really do care about the causes their charities are supposed to be addressing. But rather than simply donating part of their salaries to an established charity, they create their own, often as a result of advice they get from agents. As a board member of a charity established by former Bull Andre Barrett mentioned, part of the rationale for the charity was to expand Barrett’s “brand.”

We tend not to blame athletes like former Blackhawk Brian Campbell, who wanted to address autism, or current Bull Carlos Boozer whose charity focused on sickle cell anemia. We don’t know what advice Boozer got from his agent, Rob Pelinka, who negotiated his five-year free agent contract with the Bulls, or what Diego Bentz, who represented Alfonso Soriano, told him when he signed his latest (and second) contract with the New York Yankees, but assume this: Athletes play their sports, but the agents, who are mostly lawyers, should be able to help charitably minded athletes set up real, viable, accountable charities.—Rick Cohen