August 25, 2014: ThinkAdvisor

The issue of how much nonprofits should spend on fundraising has been a topic of heated discussion for a long time, and has given rise to several watchdog groups, such as the Better Business Bureau’s Wise Giving Alliance, Charity Watch, Charity Navigator, and others. The aim of these groups is to help prospective donors see how much of their money goes to programming and how much is spent on fundraising. Recently, the Nonprofit Federation of the Direct Marketing Association (DMANF) established a new dashboard tool to allow nonprofit organizations to self-report on their fundraising expenses. The watchdog groups swiftly responded, saying the tool is ultimately meaningless.

The Nonprofit Federation is the nonprofit arm of the Direct Marketing Association, a trade association “dedicated to advancing and protecting responsible data-driven marketing.” Last year, the DMANF Ethics Committee and the Advisory Council published a set of fundraising principles, and this new dashboard tool is based on some of the assumptions inherent in the new principles. One of the basic principles is that fundraising and management in general cost money. The principles also suggest that most of the money raised by nonprofits should be applied towards fulfilling the stated mission. So far, there is no disagreement with the watchdog groups, although DMANF does not give guidance as to what an acceptable percentage spent on fundraising might be. (BBB Wise Giving Alliance, for example, suggests no more than 35 percent should be spent on fundraising.)

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

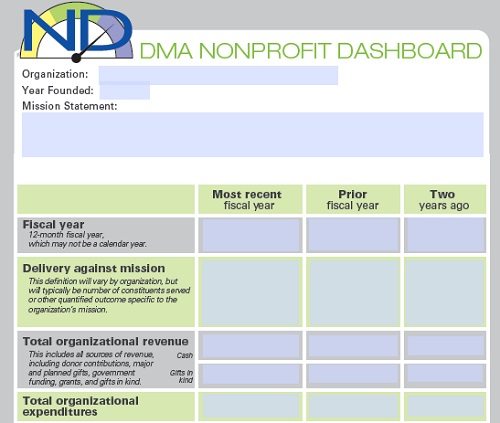

The real divergence is on the issue of time. The BBB and others measure spending and income annually, while DMANF says that an examination of spending over the course of three or more years provides a better look. Their argument is that the costs to acquire a new donor are relatively high and only pay off over time, as the donor moves to making annual gifts that increase in size. Taken over time, the initial cost to acquire the donor is mitigated. As a result, the dashboard tool asks for three years of information, and so can demonstrate trends.

The dashboard, which comes in the form of a downloadable PDF where information can be filled in, saved, and recorded online, invites the nonprofit to self-report information for the past three years about the mission, total revenue, the number of constituents served, program expenditure, expenditure to acquire new donors, the number of new donors, and more.

Charity Navigator’s Sandra Miniutti, in an interview by the Chronicle of Philanthropy, commented that there is no “independent” oversight of the information being provided in the dashboard. Moreover, it hides how much donors are actually giving, meaning that a lot of money may have been spent to acquire donors who stay at very small giving levels. Therefore, the dashboard seems to have been “written for the groups that oversolicit,” according to Charity Watch’s Dan Borochoff.

Essentially, the DMANF believes the dashboard tool is more reflective of the real expenses associated with fundraising, and then leaves it up to the prospective donor to determine if they are comfortable with the ratios and the trends over time. The watchdogs are saying there must be analysis of the information in order for donors to get any real value from the report. However, the watchdogs themselves often differ completely in judgment of the same nonprofit. As NPQ has reported, one nonprofit—the Wounded Warriors Project—received a poor rating, a decent rating, and a high rating from three different watchdog groups.

There is something commonsensical about a tool that gives quick and easy access to basic information, allowing a prospective donor the chance to review it and make up his or her own mind. However, it is valid to criticize that tool for not providing information about the number of donors at varying giving levels, whether they have increased their gifts, and other related information that would justify acquisition costs. Perhaps, in the end, this new tool needs a bit of refinement.—Rob Meiksins