Cheryl Casey / Shutterstock.com

In 2011, BP America’s foundation made grants of $14.2 million to U.S.-based nonprofits and just short of $6 million to overseas charities. The foundation’s 990 indicated three grants to Alabama-based organizations (two United Ways, one Red Cross), one in Mississippi (United Way), and none in Louisiana or Florida, the four states hardest hit by the Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion (killing 11 workers) and subsequent oil spill in 2010.

In comparison, there were 12 BP Foundation grants to Alaskan organizations. But the Deepwater Horizon disaster occurred not in Alaska, but in the Gulf of Mexico, southeast of Louisiana, becoming the biggest oil spill in U.S. history and perhaps the nation’s worst environmental disaster ever. BP’s disaster slammed the Gulf Coast economy, still reeling at that point from Hurricane Katrina, with impacts on marine wildlife, fishing, tourism, and public health. Putting a dollar figure to the economic impact of the oil spill is all but impossible. However, BP is going to be shelling out loads of money to Gulf Area nonprofits—and plenty of other entities—for a very long time as a result of the devastation it caused to the entire Gulf Coast economy, enveloping nonprofits and their revenues in its wake. You can add a couple of zeroes to whatever moneys BP was used to distributing to nonprofits through its corporate foundation, however, as the costs to BP under this settlement formula are going to reach well into the billions.

Why? In past settlements of corporate wrongdoing or negligence, a fund would be created and an administrator would examine each claim on its merits to determine whether the claimant suffered injury due to the corporation’s behavior. The new BP settlement, replacing the slow-moving fund that had been slogging along with payments, is different. If your nonprofit entity existed in the region of impact sufficiently long enough prior to the Deepwater Horizon disaster, and if it can demonstrate that it suffered losses, you get compensation as per a court-ordered formula regardless of the degree, if any, to which BP caused those losses. Moreover, it’s not a first-come, first-served capped fund. There is no cap on BP’s liabilities under this settlement.

It’s not hard to imagine the reaction in the halls of BP’s corporate headquarters. Who the heck would agree to a formula settlement without requirements of causality or a funding cap? What is going to be the necessary restatement of costs to BP’s bottom line to factor in this potentially massive financial liability? After having inked the deal, BP has been choking on the formula and nonexistent cap, fighting the settlement it agreed to as though it were foisted on them in the dead of night by a snake-oil salesman.

BP’s Deepwater Horizon settlement may well be the region’s largest funder of nonprofit organizations in history, but it poses some interesting challenges to the nonprofit sector. Based on the coverage to date, what’s clear is what isn’t clear. This article examines some of the confusion and concerns of this unprecedented corporate disaster settlement:

- How did the BP settlement emerge, and how does it operate in different parts of the Gulf Coast region?

- How is the money flowing? Who has gotten what?

- What does this kind of settlement portend for future corporate settlements that may involve nonprofits?

The Fund and the Settlement

After the disaster, BP was facing boatloads of financial liabilities, both criminal and civil. It faced penalties for violating federal laws and liabilities for a range of other damages. In response to the civil side, BP set up a fund—the Gulf Coast Claims Facility (GCCF)— relatively quickly, and had it administered by the widely respected lawyer Kenneth Feinberg of the Feinberg Rosen law firm. Feinberg has specific expertise in this area; he has served stints administering payments from the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund, the Aurora Victim Relief Fund, the Penn State Settlement (payments due to the sexual abuse conviction of former Penn State assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky), and most recently, the One Fund to compensate victims of the Marathon bombing in Boston. Feinberg was also the nation’s “pay czar” for the U.S. Treasury Department ruling on executive compensation at companies receiving TARP (bailout) assistance.

In the BP scenario, Feinberg was criticized for being too close to BP, or even controlled by BP (as his firm was paid by BP to administer the Fund), even though Feinberg claimed to be independent of BP influence in his decision-making. Claimants complained at what they perceived as subjectivity in the decisions, with some claimants getting payments and others not, until a federal judge finally ruled that Feinberg was anything but independent, especially as his firm and BP both made disclosures of the terms of compensation that were vague at best. Claimants against BP turned into complainants against Feinberg’s administration of the fund, with many opting out of the process until the GCCF was finally closed to claims.

In 2012, to replace the GCCF, BP and the courts reached a settlement agreement that outlined procedures for economic and property damages (in addition to seafood compensation, coastal property real damage, wetlands damage, and other damages) for a large class of potential beneficiaries—including nonprofits—in the Gulf Coast area. Amidst the reams of legal documents from the court, the process for nonprofits to participate in submitting claims is surprisingly straightforward, which was in part one of the reasons why the courts switched from the GCCF.

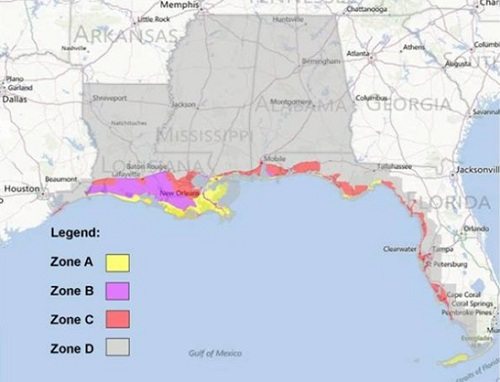

We spoke to Zachary Wool and Dawn Barrios the Barrios, Kingsdorf & Casteix law firm to explain it, because they represented the first nonprofit to successfully apply for compensation from BP under the new settlement —the Contemporary Arts Center in New Orleans. As opposed to the situation with Feinberg, who was essentially on contract to BP to administer a BP fund, BP is completely insulated in the new settlement process from the decision-making dynamic. Wool explained that nonprofits are permitted as claimants if they functioned in any of four geographic economic loss zones, largely reflecting the court’s determination of the degree of impact of the BP oil rig disaster.

The eligibility for nonprofit businesses in each zone is objective, based on finances, not on a subjective determination of causality by a fund administrator, as explained in the settlement agreement:

- Zone A: nonprofit businesses with economic losses are automatically eligible

- Zones B and C: total business revenue (including grants) showing a “V-shaped pattern” of an aggregate decline of 8.5 percent over a three-month period between May and December of 2010, compared to a previous benchmark period (as far back as the same three months in 2007), followed by a later upturn of 5 percent for the same three month period in 2011; or alternatives, such as a decline-only pattern of a 8.5 percent decline that doesn’t recover in 2011 because of factors that prevented a subsequent increase in revenues

- Zone D: a deeper V-shaped revenue curve with a 15 percent aggregate revenue decline followed by an aggregate 10 percent increase, or alternative formulations that allow for lower percentage increases—again, by demonstrating factors that reduced the potential recovery

Some nonprofits aren’t eligible, particularly nonprofits that engage in lending or banking functions, because of a prohibition of for-profit lenders in the process. That, unfortunately, effectively excludes Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs). Nonetheless, the human factor of eligibility is largely out of the picture. If the numbers work, an organization gets compensated. BP can appeal the decisions, but it doesn’t see them until after the award letter is issued.

The experience of Wool and Barrios with the CAC is important, because the CAC was originally denied compensation under Feinberg’s GCCF. Located in Zone A, the CAC might not appear to be the sort of organization that would be directly harmed by an off-shore oil spill, but it fit the criteria, made the case, and received a payment of several hundred thousand dollars, a decision which BP strenuously contested.

One can easily imagine why BP is challenging anything and everything, starting with the settlement agreement itself. First, it is uncapped, so the payments can extend to as many entities as can demonstrate that they suffered economic losses under the zonal formulas. As a result, BP has upped its estimate of potential charges it will face under this formula from $7.8 billion to $8.5 billion. In addition, by allowing the “V-shaped revenue curve” to use data as old as 2007, nonprofits will basically draw on their financial status, which could reflect high revenue streams generated by post-Katrina charitable and philanthropic contributions that were, logically, much higher than what they probably got in 2010, BP or not. So for many nonprofits, once they demonstrate eligibility, it may be much easier for them to prove losses that generate compensation, compared to the much smaller proportion of claimants—38 percent—that received compensation under Feinberg’s GCCF.

Money and Lawyers

The current BP settlement is a fast-moving train. Although challenged by BP repeatedly, including most recently in early April, the settlement has disbursed over $2 billion to affected businesses and individuals, according to court-appointed settlement administrator Patrick Juneau, a lawyer based in Lafayette. That’s $2 billion under the formula process that started only in June of last year. Juneau says that his office has reviewed and found eligible at least $3 billion worth of claims.

Although this process is a lot more formulaic than other kinds of settlements, individuals, businesses, and nonprofits are finding the assistance of lawyers helpful, though lawyers seem to be coming out of the woodwork to make themselves available—for a fee, of course—to help groups get their rightful share of BP’s money. Without casting aspersions on lawyers in general, as there are plenty committed to the nonprofit sector who work hard to make sure nonprofits get their share of potentially available resources, some of the lawyers offering services give the feel of the television ads telling you to call 1-800-BAD-DRUG.

For example, if you call 1-800-BP-CLAIM, you’re connected to a lawyer referral service prepared by an entity called ACCESSWWW LLC. They say on their website that their “network” of lawyers “gets BP Claims Paid” at a fee ranging between 15 and 25 percent. New Orleans lawyer Charles Mansour can be found at BP Settlement Now. Houston attorney Paul Danziger has a website titled BP Gulf Coast Settlement Assistance. Three Birmingham, Alabama, law firms have come together to create a BPSettlementNews website with a handy online form to connect you to a lawyer for a free evaluation of your potential case.

It seems that the 15 to 25 percent cut of the lawyers may be the general range of fees, with Barrios explaining that the court restricted the maximum fee to 25 percent. Therefore, the gross totals of payments don’t necessarily mean that they all go to people, businesses, and nonprofits in need. Rather, if BP’s own report of payments is correct, of the $2.078 billion it says it has paid for economic and property damage in the court-supervised settlement program that replaced the Gulf Coast Claims Facility and Transition Program, perhaps $300 million to more than $600 million has gone to lawyers and other intermediaries (probably accountants) who have been preparing and facilitating claims. BP’s latest report on all of its payments is here:

|

BP Report on Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill Claims and Other Payments as of April 30, 2013 |

|

|

Total Payment Overview |

ITD |

|

Individual & Business |

$395,619,857 |

|

Claims Paid by BP Prior to August 23, 2010 |

|

|

Gulf Coast Claims Facility and Transition Program |

$6,670,705,516 |

|

Court Supervised Settlement Program |

|

|

Economic & Property Damage |

$2,078,008,675 |

|

Medical |

$20,732,508 |

|

BP Claims Program |

$4,463,903 |

|

Total Paid – Individual & Business |

$9,169,530,459 |

|

Government Entities and Other Payment |

$737,808,622 |

|

Government – Advances, Claims & Settlements |

|

|

USCG/Federal Payments |

$704,683,315 |

|

Total Paid – Government |

$1,442,491,937 |

|

Total Paid – Other |

$316,275,661 |

|

Total Payments |

$10,928,298,057 |

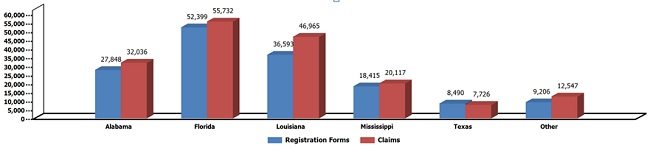

As a result of the significant role of intermediaries marketing their services, it is difficult to determine if the balance of claims and payments reflects the distribution of affected individuals and firms or the marketing and accessibility of the intermediaries themselves. For example, in the following chart from Juneau’s latest report, Florida tops the list of the number of filings and number of claims:

Within the payments for individuals and businesses, it is impossible at this point in Juneau’s reporting to identify the portion that may have gone to nonprofits.

|

Economic and Property Damages Settlement Payment Information |

||||||

|

Claim Type |

Eligibility Notices Issued with Payment Offer |

Payments Made |

||||

|

Number |

Amount |

Number |

Amount |

Unique claimants Paid |

||

|

Seafood Compensation Program |

6,356 |

$911,730,678 |

4,166 |

$788,420,410 |

2674 |

|

|

Individual Economic Loss |

1,255 |

$14,281,199 |

920 |

$10,140,962 |

920 |

|

|

Individual Periodic Vendor or Festival Vendor Economic Loss Sign up for our free newslettersSubscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox. By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners. |

3 |

$7,961 |

2 |

$5,178 |

2 |

|

|

Business Economic Loss |

7,121 |

$1,695,214,754 |

5,138 |

$840,505,277 |

4981 |

|

|

Start-Up Business Economic Loss |

292 |

$60,948,775 |

212 |

$30,872,036 |

201 |

|

|

Failed Business Economic Loss |

7 |

$703,733 |

3 |

$589,357 |

3 |

|

|

Coastal Real Property |

15,341 |

$94,874,774 |

12,286 |

$73,257,288 |

9832 |

|

|

Wetlands Real Property |

1,452 |

$82,111,962 |

1,257 |

$54,965,847 |

563 |

|

|

Real Property Sales |

373 |

$21,469,696 |

344 |

$20,751,074 |

319 |

|

|

Subsistence |

440 |

$4,010,282 |

313 |

$2,787,617 |

313 |

|

|

VoO Charter Payment |

6,793 |

$274,191,170 |

6,376 |

$260,646,618 |

4894 |

|

|

Vessel Physical Damage |

445 |

$8,584,444 |

348 |

$4,922,403 |

335 |

|

|

Total |

39,878 |

$3,168,129,427 |

31,365 |

$2,087,864,065 |

25037 |

|

Presumably, nonprofit claims are largely going to be in the “Business Economic Loss” category of payments.

Calculating Economic Impacts

With more claims to come in, nonprofits might be significant participants in what could turn out to be billions of dollars of compensatory payments from a reluctant BP. But how much did nonprofits suffer from the Deepwater Horizon disaster? Despite BP’s continued distaste for this mechanism, payments calculated based on a formula that removes the subjective element of human opinion become an important new measure for calculating impact and compensation from disasters.

In this case, at 9:45 in the morning on April 20, 2010, the wellhead of the Deepwater Horizon floating semi-submersible oil drilling rig exploded. Until it was capped on July 15, 2010, the underwater oil well spewed 4.9 million barrels of oil (BP says it was only 4 million barrels) into the Gulf of Mexico, contaminating 491 miles of coastline in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida.

From the point of the spill onward, the economy of the region changed. An entity didn’t have to be engaged in fishing or tourism to be affected by the disaster. BP’s environmental catastrophe disrupted not just the ecology of the region, but the economy. By treating nonprofits as a class of business with economic interests of no lesser importance than any other sector of the economy not specifically engaged in fishing, tourism, or oil drilling, the settlement recognized that nonprofits are crucial actors in an economic ecosystem. The extent to which their revenues and prospects increased or decreased after the BP disaster says that nonprofits aren’t an extra optional appendage, but a sector that merits the same consideration as any other.

Of course, not all corporate settlements address environmental disasters that undo a region’s economy as specifically and effectively as 86 days of an oil spill by BP. But the economic crimes of corporations can just as effectively uproot and undermine regional and national economies. Although, for example, some of the nation’s biggest banks—Bank of America, Wells Fargo, JP Morgan Chase, Citigroup, and Ally, among others— have been hit with settlements for their destructive lending and foreclosure behaviors, their impacts were not just on the families they displaced, but on entire city and regional economies. In some instances, corporations have been arguing their responsibilities too narrowly. The BP settlement represents a shift in this discussion, compelling a corporate malefactor to take responsibility for the direct impact of its wrongdoing and for the ripple effects on the economy at large.

As a result of a formulaic approach to damages, could some entities in the Gulf Coast get compensated for losses that might have occurred even in the absence of the Deepwater Horizon spill? Not only is that possible, it was acknowledged by all parties as they negotiated this settlement. But it is certainly no less fair than a compensatory process in which a human decision-maker applies criteria and, because of better or worse presentations and representation, makes decisions that overcompensate some and undercompensate others.

For nonprofits, understanding that corporate settlements that permit funds to go to nonprofit claimants and beneficiaries is a new arena that merits better information and more consistent attention. For example, how many nonprofits were aware in 2005 that the settlement of Oracle chief Larry Ellison’s insider trading lawsuit called for $100 million in donations to charity—though Ellison would personally name the charity or charities to benefit from his conviction? Who monitored the distribution of grants to nonprofits through the Local Initiatives Support Corporation and the Neighborhood Reinvestment Corporation from a settlement in the late 1990s between the Department of Justice and Nationwide Insurance for Nationwide’s violation of fair housing laws due to insurance redlining?

Increasingly, nonprofits are the named beneficiaries of corporate settlements, though sometimes the corporations get to control some of the payments to nonprofits and even get to claim them as business—or worse, charitable—deductions. Sometimes the payments are controlled by the governmental entities that brought the corporations to the table—the Department of Justice, Treasury, HUD, EPA, state attorneys general, etc.—with varying degrees of public attention, disclosure, and official reporting. Sometimes, private or even nonprofit intermediaries get to play roles that merit scrutiny just to see how much value they really add to or take from the process.

Somewhat surprisingly, it doesn’t appear that nonprofits have truly flooded the claims process. Some may think that the need to demonstrate the BP spill’s impact on variable profits (the additional criteria in zones B, C, and D) is difficult, or perhaps even thinking of nonprofit revenues in profit-and-loss terms is uncomfortable and unusual. Perhaps they think that their financial records are too shaky for demonstrating the BP-induced losses. In reality, Juneau and his team will work with strong financials as well as compilations of bank statements to figure out impacts, in a way, developing a P&L statement for a nonprofit from the information the nonprofit claimant submits. The settlement isn’t just for big nonprofits with top-flight accounting records. Although the formulas look complex, they can be boiled down to something of a science. As Wool explained, the variable profit formulas allow for multiple combinations of months and years for making the comparisons, but a solid accountant can test alternative combinations, run various scenarios, and figure out which ones work best.

There also seems to be a self-imposed reticence on the part of some nonprofits to make claims against BP, assuming that even though they suffered revenue losses, they might not have been directly caused by BP. In a way, they are policing themselves out of the benefits they are entitled to. The court made the determination that BP caused economic losses to the region, nonprofits as well as for-profits. That is why the efforts of organizations such as the Louisiana Association of Nonprofit Organizations and the Louisiana Cultural Economy Foundation to tell nonprofits about the settlement and their rights. Aimee Smallwood, the CEO of the Foundation, has become something of her mission to get the word out to nonprofits in the region. As Wool said, this is a “region that keeps getting kicked in the teeth” from natural and man-made disasters. In these difficult economic times, to offer nonprofits in the Gulf Coast area the opportunity to find resources to continue their missions and recover from losses that were outside of their control is legitimate and important.

Despite continued lobbying from the business world that it would do quite well, thank you, if government simply got out the way and deregulated, there has been a cultural shift in our society to take a closer look at corporate malfeasance. Generally, the pressure doesn’t come from government—look at the bankers who have escaped without trial or conviction for their roles in bringing down much of the economy late in the last decade—but from nonprofits that raise issues of corporate misbehavior that government eventually has to acknowledge and prosecute. The penalties are usually financial, often with nonprofits mentioned in the mix as recipients. As the BP process demonstrates, it is well worth the time and attention of the nonprofit sector to ensure that nonprofits get what they deserve as compensation from corporate behaviors that disrupt local and regional ecologies and economies.