February 24, 2015;Washington Post

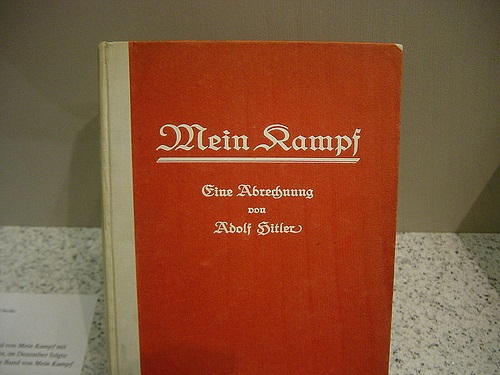

After almost 70 years since the conclusion of the Second World War, Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf, or “My Struggle,” will be gracing Germany’s bookstores once again in 2016. A new annotated version of the book in German will be published next January and will be nearly three times as long as the original, with additional commentary and criticism about Hitler and Nazi Germany.

While Germany never banned the book, unlike Russia and parts of Europe, the state of Bavaria has had the exclusive rights to reprint the book and had not allowed the book to be published in Germany since the war. However, the rights will expire next January, at which time it will legally become available in Germany once again. Taxpayer money is financing the publication by the historical society, the Institute of Contemporary History, at the helm of the reprint.

The reaction to the release of Mein Kampf, which is widely available in the United States, Canada, and India, among other countries, has been understandably mixed. To many, the book is an emblem of a dark past they are afraid may resurface with a reprinting. While published years before the Holocaust, the book foreshadowed much of the rhetoric that drove the war. Consider, for example, the description of the Jewish people as “the eternal parasite, a freeloader that, like a malignant bacterium, spreads rapidly whenever a fertile breeding ground is made available to it.”

For some, the publication of the book is particularly dangerous given the growing anti-Semitic climate in Europe the past several years. From organizations to the local German communities, opposition to the reprint has been pronounced:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- “I am absolutely against the publication of Mein Kampf, even with annotations. Can you annotate the Devil? Can you annotate a person like Hitler?” said Levi Salomon, spokesman for the Berlin-based Jewish Forum for Democracy and Against Anti-Semitism. “This book is outside of human logic.”

- “This book is too dangerous for the general public,” said Bavarian State Library historian Florian Sepp.

- “This book is most evil; it is the worst anti-Semitic pamphlet and a guidebook for the Holocaust,” said Charlotte Knoblock, head of the Jewish community in Munich, Hitler’s home during the war. “It is a Pandora’s box that, once opened again, cannot be closed.”

The Institute for Contemporary History emphasizes that the reprint will make available a vital academic tool, a 2,000-page book with analysis and critique. Some of the funding for the reprint has come from the Bavarian state itself, which has recognized the historical benefit of the extended version.

“I understand some immediately feel uncomfortable when a book that played such a dramatic role is made available again to the public,” said Magnus Brechtken, the institute’s deputy director. “On the other hand, I think that this is also a useful way of communicating historical education and enlightenment—a publication with the appropriate comments, exactly to prevent these traumatic events from ever happening again.

Hitler crafted the rambling manifesto 20 years before he took power in Germany while he was in a Bavarian prison following a failed Nazi uprising in 1923. The book was published first in 1925 and then later in 1926, and became known as almost a founding text for Nazism. If you haven’t read it just yet, Orson Welles’ commentary on the manifesto at a time when Nazism was in full throttle would suffice:

“What [Hitler] envisages, a hundred years hence, is a continuous state of 250 million Germans with plenty of “living room” (i.e., stretching to Afghanistan or thereabouts), a horrible brainless empire in which, essentially, nothing ever happens except the training of young men for war and the endless breeding of fresh cannon-fodder. How was it that he was able to put this monstrous vision across?”

—Shafaq Hasan