April 13, 2015; Washington Post

The horrific news of the week was the incident from Tulsa, Oklahoma, where a 73-year-old reserve deputy shot and killed an unarmed black man. The reserve deputy, an insurance company executive, mistook his sidearm for a taser and shot 44-year-old Eric Harris. After realizing that he had killed Harris with his handgun, the reserve sheriff’s deputy, one Robert Bates, said, as captured on another officer’s body cam video, “Oh, I shot him. I’m sorry.”

The Tulsa County District Attorney, Steve Kunzweiler, charged Bates with second-degree manslaughter—that is, killing the unarmed man not with malicious intent, but due to culpable negligence, “the omission to do something which a reasonably careful person would do, or the lack of the usual ordinary care and caution in the performance of an act usually and ordinarily exercised by a person under similar circumstances and conditions.”

Why was an amateur cop allowed to carry or provided with taser and handgun and authorized to do things one would assume professional police officers do, presumably with the kind of training that a reserve deputy might lack? In the case of Bates, he seems to have been able to become a reserve deputy by virtue of his political and charitable donations. He was the chairman of the campaign to reelect the Tulsa County sheriff in 2012, a donor to Sheriff Stanley Glanz’s campaign, and reportedly a donor of equipment to the sheriff’s office as well.

According to Donna LaMontaine, president of the Deputy Sheriffs Association of Michigan, “These people drop four or five grand and dress up to look like police.” The Tulsa County sheriff’s department sometimes recruits reserve deputies who make donations to the department to help out local police—and they are permitted to bring along their own weapons when on police assignments.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In light of the problem of shootings of unarmed people by professional cops, does it make sense to have less-trained part-timers armed and patrolling the streets by virtue of their charitable contributions—and, in some cases, their personal fame? The public probably knows of some celebrities who have experimented with the role of deputy police officer, notably Shaquille O’Neal and actor Steven Seagal. Seagal’s experiences as a deputy officer in Jefferson County, Louisiana, and Maricopa County, Arizona, were filmed for a reality TV show, Steven Seagal: Lawman, which aired on the A&E channel. Despite Seagal’s multiple movie roles as a cop, his experience on the show, if you’ve watched any episodes, suggested that the real cops weren’t about to have him doing real police work with the potential of causing the kind of harm that Bates has.

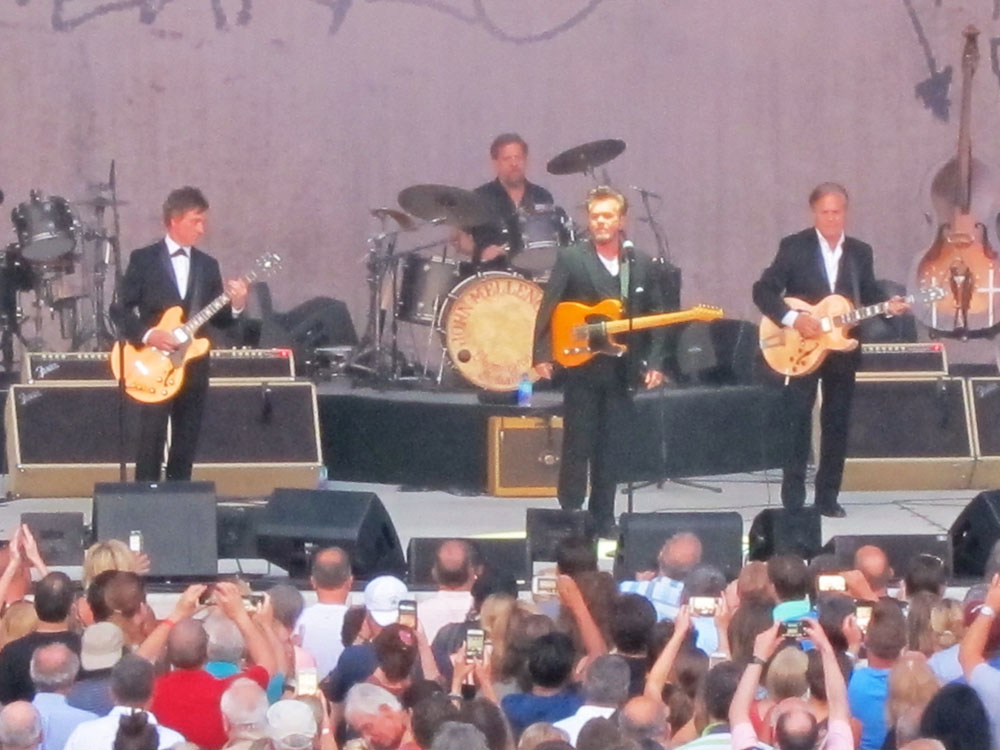

Maybe helping out around the Tulsa Sheriff’s Department office, answering phone calls and taking down information from complainants, might have been a good volunteer role for Bates, but sending him out on patrol armed with lethal weapons sounds scary. But allowing for armed auxiliary police is a relatively common practice. In the little town of Oakley, Michigan, with a population of less than 300, auxiliary cops include Grammy-award winner Kid Rock, who is one of 150 reserve officers there, making the little rural community one of the nation’s best in terms of police/population ratio. It isn’t hard to figure out what Oakley is doing. Rock, whose real name is Robert James Ritchie, is named in a suit filed by a local attorney, Philip Ellison, who argues that the reserve officers gimmick in Oakley is simply a “pay to play scheme.”

Documents indicate that about half of the reserve officers in Oakley have made voluntary contributions to the community, totaling about $180,000, but Oakley’s officials are resisting a demand for disclosure of the names of the donors and the amounts of their donations, despite the state’s open records law, because, it seems, Oakley is protecting the donors’ philanthropic confidentiality. It isn’t totally clear, but it seems that the Oakley reservists pay $1,300 apiece for a uniform, handgun, and vest. The state of Michigan has come out on the side of the attorney who has requested the disclosure of the information, describing the donors as “phantom philanthropists,” in that they made their donations for the quid pro quo of getting the reserve police officer appointments and, as official employees of the Oakley police department, cannot claim exemption from state or federal freedom of information suits. Among the other luminaries working as reserve cops in Oakley are Matt Cullen, an executive working for Dan Gilbert’s Rock Ventures, and former Detroit Lion, now Miami Dolphin player Jason Fox.

The septuagenarian Bates was a reserve deputy in Tulsa in part because he made donations to the Sheriff’s department, including cars and equipment (apparently purchasing “sunglass cameras”). CNN notes that if Bates had been an auxiliary police officer in New York City, for example, he would have been able to wear a NYPD uniform but he would not have been permitted to carry a handgun like the one he used to kill Eric Harris. Had he worked for Anne Arundel County, Maryland, he would not have carried a gun as an auxiliary officer, nor would he in Nassau County, New York, but if he had been an auxiliary cop in Suffolk County, next to Nassau on Long Island, he might have been allowed to carry.

The rules concerning the powers and armaments allowed for auxiliary officers are a mess. There is no way you might know whether the cop with a handgun pulling you over is a highly trained professional police officer or an amateur “pretend cop” who might actually be a doctor, lawyer, or, like Bates, an elderly insurance executive masquerading as a real police officer. Moreover, you might not know whether the auxiliary cop was vetted and trained or simply got his post, badge, and uniform because he made a charitable contribution or two to the police department.

It is a fundraising aphorism that donors give more to the organizations where they get to volunteer. Selecting and arming volunteers for police duty by virtue of their willingness to buy a police department a car or vests or cameras is a dangerous formula for charitable giving for public safety. Just ask the family of Eric Harris.—Rick Cohen