May 10, 2015; Miami Herald and Winston-Salem Journal

Here are two examples of the importance of nonprofits developing dialogue and constructive relationships with their neighbors, and how a failure to do so can derail the best-laid plans regardless of the “targeted demographics” of the proposal. In one case, a museum with international aspirations goes head-to-head with a local neighborhood historic preservation group; in the other, residents of a low-income community fight off plans to locate a homeless shelter in their midst. In both cases, the nonprofits failed to be good neighbors and talk to the local folks first.

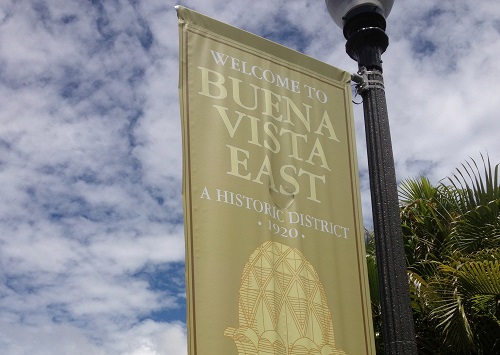

The Miami Herald reports on the problem confronting the Institute of Contemporary Art-Miami (ICA), whose new home was envisioned as a “cutting-edge” institution that would serve as “the crown jewel of the city’s luxury shopping mecca.” But it turns out that while half the museum campus is in the so-called Design District, the other half is in a neighborhood called Buena Vista East—“a historic district where homeowners are now pushing back against the museum’s plans.”

The paper reports that there have been disagreements between ICA and local residents for months, and they were working toward a resolution before talks fell apart and their disagreement went public last week, “potentially delaying construction and possibly complicating plans.”

The museum is being built entirely with private funds, mostly from philanthropist Norman Braman and his wife. The city needs to rezone the entire campus and allow the demolition of three duplexes in the rear. There were hearings scheduled this week, but the vote on the demolition was delayed until June, and vote on rezoning was pushed back to July.

“You are putting a museum in the middle of a residential neighborhood…I don’t understand how the city can support that,” said one local resident. The local historic neighborhood association told the Herald that they are worried about the height of the building and its encroachment into the neighborhood.

Neighborhood activists say they were working together until the museum “chose to delay a vote by the city’s historic board and pursue a zoning change without first getting approval to demolish the homes.” The museum says the neighborhood reneged on a prior agreement.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Miami’s City Commission has final say on the rezoning and demolition. It will have to engage in a political balancing act between a powerful community association, historic preservation and the opportunity to put Miami on the map as a world-class center of arts and culture.

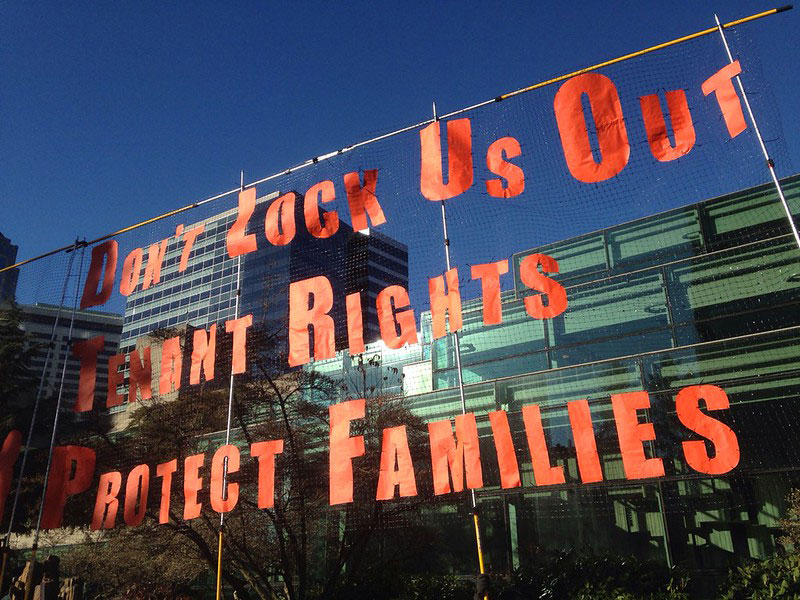

Up I-95 in North Carolina, residents of East Winston-Salem are opposing the Salvation Army’s proposal to convert a day-care center into a homeless shelter for families, “saying it isn’t a good fit for a neighborhood trying to attract new businesses and development,” according to the Winston-Salem Journal.

The Salvation Army has asked the local planning board to rezone the area from institutional and public to limited special-use, so it can put the shelter near its emergency assistance office. The paper reports that the “proposed shelter would house women and children and, when necessary, families with single fathers.” Right now, the low-income neighborhood is populated with small businesses, churches, affordable housing, and single-family homes.

The planning board approved the measure 7-2 and sent the petition to the Winston-Salem City Council, which will consider the matter in July. The Salvation Army bought the property from a church, and now tells the Journal it “will take another look at the proposal.”

The owner of a pharmacy two blocks from the proposed shelter said she doesn’t think it would be good for the neighborhood, which is in transition. A local community development leader told the paper that “a homeless shelter should be near such services as the Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Social Services and job services.” Those are located in the city’s downtown area.

The neighborhood is part of a redevelopment zone and is focused on revitalization, its master plan having been approved by the city in 2012. Local leaders don’t regard a homeless shelter as fitting in with that vision for the future.

“Our biggest concern is that the residents’ dreams won’t be adhered to. […] Having a shelter there is not compatible with what we’re trying to do at this time,” said the director of the city agency that helped develop the plan. The Salvation Army says it was surprised by the community’s opposition and believes its plan will help the neighborhood revitalization efforts.—Larry Kaplan