Joseph Sohm / Shutterstock.com

May 18, 2015;Task & Purpose

It should be no surprise to NPQ readers that veterans of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars who return to rural areas in the U.S. face a variety of challenges. According to James Clark, writing for Task & Purpose, veterans in rural areas find their interactions with the Department of Veterans Affairs “a source of apprehension and stress, rather than relief.”

For example, Mickey Ireson, a resident of Hastings, Nebraska, takes a six-hour drive to Omaha for his appointments with VA doctors and caregivers. Add in the time the appointments themselves consume, and it means that on VA appointment days he loses a day of class time or a day of wages. Ireson has been diagnosed with PTSD, suffers from anxiety, anger, and depression problems, and has other physical ailments. The VA services are important—if they are accessible and useful.

Clark acknowledges that “the challenges facing rural veterans may be caused more by geography than a lack of policy reform.” The fact that this is a rural issue cannot be ignored. The Catholic Health Association reported in 2013 that 44 percent of military recruits in 2010 came from rural areas, a vastly disproportionate figure. Moreover, estimates are that 3.2 million veterans enrolled in the VA health system, roughly 35 percent of all veterans, live in rural areas, according to the VA’s Office of Rural Health.

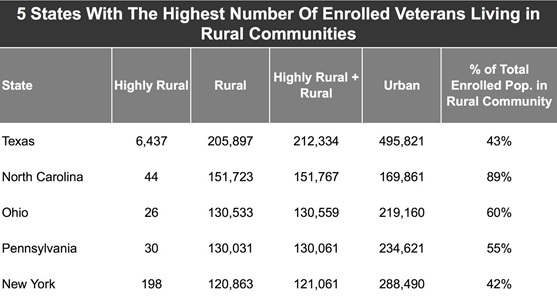

The following chart shows the states with the largest number of veterans in rural areas:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The VA reports that veterans in rural areas face the combined challenges of the VA’s bureaucratic labyrinth plus the problems of distance, limited access to facilities, and limited choices of providers and services. Clark notes that 36 percent of rural veterans have service-related disabilities and generally have health conditions that lead to a lower quality of life.

The VA isn’t unaware of the problem. Clark says that the VA’s Office of Rural Health was established in 2007 with a “mission…to improve the access and quality of care for enrolled rural and high rural veterans, and to create programs, employ strategies, and use emerging technologies to increase health care options for all rural veterans.” He quotes Hilda Heady, a researcher for Atlas Research, a rural health policy group, to the effect that rural veterans face three particular barriers: access to a VA health facility, awareness of the specific problems of rural veterans, and cultural barriers between rural veterans and their perhaps the more-urban service providers that might be offered by the VA.

Even with the efforts of the Office of Rural Health, there may be other problems related to the intersection of rural issues and the VA. Clark describes the Choice Card Program implemented by the VA last November that would allow veterans like Ireson to receive medical care from pre-approved medical providers if they had been waitlisted for more than 30 days or had to travel more than 40 miles to a VA facility. Ireson, according to Clark, said he had never heard of the Choice Card Program, consistent with the survey finding of the Veterans of Foreign Wars that only 19 percent of respondents who were qualified for the Choice Card Program were aware that they could benefit from it.

The VA doesn’t have all the answers. Clark talked to Ryan Kaufman, another veteran who lives in a small Nebraskan community, who described the limited trust many veterans have in the public and private services available to rural veterans and the importance of making personal connections. Kaufman works in the At Ease Program at Lutheran Family Services of Nebraska, providing confidential services to active military personnel, veterans, and their families. Kaufman is one of the people in the nonprofit world that serves veterans who, like Ireson, don’t see a system structured to help them. In fact, he has even helped Ireson himself.

“If 22 guys are dying in a VA in Phoenix and nobody knows about it, that’s not care. If we have a backlog of over 400,000 veterans, that’s not care. It seems as though nobody cares,” Kaufman said. “My job is to take them to those community members who do, and usually they’re the ones who have been there and done that.”

At the Philanthropy-Joining Forces Pledge event of the Council on Foundations and the White House last week, there was little if any reference to the specific issues faced by the millions of veterans in rural areas. Although the U.S. Department of Agriculture is reportedly preparing a study for release that suggests that philanthropy is doing just fine for rural America, rural nonprofits just don’t buy it. The lack of philanthropic attention to rural areas, combined with the specific challenges rural veterans face, is a double whammy for veterans like Ireson and nonprofit service providers like Kaufman. Let’s hope that the new philanthropic commitments to the Joining Forces pledge include resource commitments specifically for rural veterans.—Rick Cohen