August 3, 2015; Salon

It’s been ten years since Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast and left much of New Orleans underwater, its population displaced and its institutions devastated. The need to rebuild a school system from the ground up allowed “school reformers” to put their marketplace, performance-based theories into practice on a scale and at a pace unmatched in any other American city. Ten years in, observers are beginning to be able to measure how this experiment has played out and to see if it is a model other locales should emulate.

Douglas Harris, professor of economics at Tulane University and founder and director of the Education Research Alliance for New Orleans, described the scope of the changes that were implemented in Education Next:

“Within the span of one year, all public-school employees were fired, the teacher contract expired and was not replaced, and most attendance zones were eliminated. The state took control of almost all public schools and began holding them to relatively strict standards of academic achievement. Over time, the state turned all the schools under its authority over to charter management organizations (CMOs) that, in turn, dramatically reshaped the teacher workforce. […] New Orleans essentially erased its traditional school district and started over. In the process, the city has provided the first direct test of an alternative to the system that has dominated American public education for more than a century.”

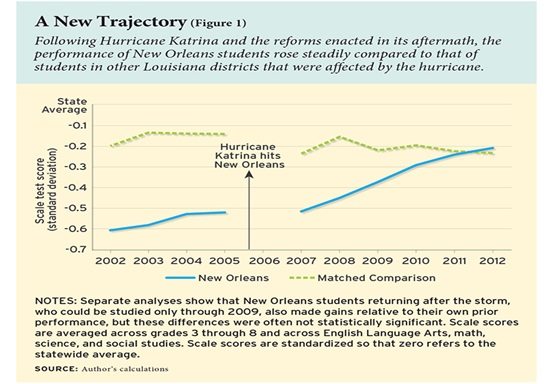

Harris and his colleagues at Tulane have just released findings from research they had been conducting on New Orleans’s schools. On the basic level of academic achievement, there seems to be some good news: New Orleans children are learning better than their peers in other parts of the state and better than they were before Katrina stuck.

“For New Orleans, the news on average student outcomes is quite positive by just about any measure. The reforms seem to have moved the average student up by 0.2 to 0.4 standard deviations and boosted rates of high school graduation and college entry. We are not aware of any other districts that have made such large improvements in such a short time.

“The effects are also large compared with other completely different strategies for school improvement, such as class-size reduction and intensive preschool. This seems true even after we account for the higher costs. While it might seem hard to compare such different strategies, the heart of the larger school-reform debate is between systemic reforms like the portfolio model and resource-oriented strategies.”

But this level of student improvement has not been without cost. Not only has the financial investment in rebuilding New Orleans’s schools been exceptionally large in terms of both public and private investment, there has also been a cost in creating a corporate management system for a public school system.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Blogger Jennifer C. Berkshire, known as EduShyster, took a look at this side of the NOLA education story in a recent Salon article. Andre Perry, former CEO of the Capital One/UNO charter network, told her, “The test scores are up, but let’s be honest about what we had to do to get there. Don’t lie to people and say ‘it’s all good.’”

One of Perry’s concerns is that in a city that is 65 percent black, the leadership of the reform effort and many of the schools within it are almost entirely white. In Perry’s view, “We can’t have a white-led reform movement in New Orleans where all of the decisions are made by three or four power brokers.”

Christy Rosales-Fajardo, an organizer for VAYLA, a group of students and young leaders from both the Vietnamese and Latino communities, is convinced that parents actually have less power in New Orleans today than they did under the prior school system. She argues that eliminating neighborhood schools has also eliminated the power of parents to come together as part of a community: “Parents are fighting individual battles with these schools and they’re all petrified of what will happen to their kids,” she says. Meanwhile, principals in the new autonomous landscape are more powerful than ever, functioning more like CEOs who report to handpicked nonprofit boards.

“That’s the power shift,” Fajardo says.

Berkshire also found that a large number of children and teens have dropped out of the public school system entirely, and their lost education is not reflected in the data set:

“There are the huge number of young people in New Orleans between the ages of 16 and 24 who are neither in school or working. The recent Measure of America study, conducted by the Social Science Research Council, found that the greater New Orleans/Metairie region is home to more than 26,000 so-called ‘opportunity youth’…the number of students who’ve dropped out of the New Orleans’ schools begins to creep up uncomfortably close to the 43,000 students who are still in them.”

In a recent blog post, Michael Stone, CEO of New Schools for New Orleans summed up the challenges still to be faced in New Orleans and in every urban school district looking for direction:

“An encouraging decade of academic growth hasn’t erased the pervasive sense that reform was done ‘to’ the city, rather than via collective action by citizens, veteran educators, and African American families in New Orleans. And our city’s progress hasn’t cured the social ills that young people here face: poverty, violence and trauma, sky-high incarceration rates, fractured mental health services. That is a daunting list.”

And Professor Harris also thinks that what has happened positively in New Orleans should be taken with a large grain of salt by educational leaders looking for answers in their own school districts. “Unfortunately, the effects of even the most successful programs are often not replicated when tried elsewhere, and there are good reasons to think the conditions were especially ripe for success in New Orleans.”—Marty Levine