March 17, 2016; New York Times

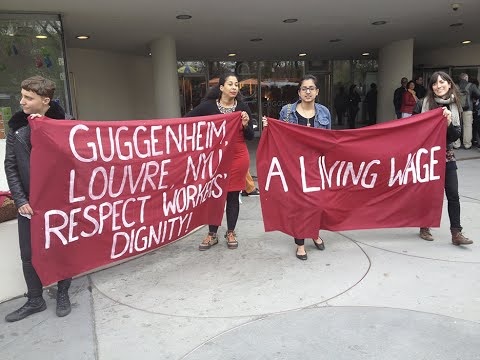

Art that serves a moral function is not a new concept. Since antiquity, artists from every cultural background have created works that are meant to instruct the viewer in some ethical maxim or to communicate a significant principle. In recent history, artists have taken more radical approaches to moral instruction. In December, environmental activists staged a protest outside the Louvre as the United Nations climate policy negotiations went on in Paris. The demonstrators carried black umbrellas that spelled out the phrase “Fossil Free Culture,” protesting the museum’s sponsorship ties to two of the world’s largest oil companies. Other artist-led protests at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim have focused those museums’ connections to dubious corporate entities, primarily through board members or other sources of donations.

When artists protest against museums, it seems as though there is a conflict between the moral code of the institutions that exhibit the art and the creators of the art themselves. But are museums, themselves, intrinsically moral? Or does ethical instruction depend entirely upon the artwork that the institution displays? Holland Cotter argues that urban museums have become “destination brands.” He describes modern museums as “busy, event-driven entertainment centers,” rather than “generators of life lessons, shapers of moral thinking, [or] explainers of history,” as they used to be. Are museums themselves supposed to be the educators, rather than the instruments?

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

To illustrate his point about the moral failings of museums, Mr. Cotter points out various moments in recent history when curators have stumbled and produced incoherent and even offensive exhibits that failed to communicate their purported moral purpose. Cotter highlights “Harlem on My Mind,” which the Met supposedly mounted to showcase African-American art but which failed to actually feature any works by black artists. This is the sort of grave curatorial mistake that alienates and excludes large groups of audience members.

Yes, it is true that the Met has a collection that is extensive enough to “yield many narratives,” and these narratives can and should be revised, corrected, and expanded frequently and thoroughly. But Cotter seems to think that a museum is only as good as its curators. Before the rise of curating, a museum was simply a collection. As Cotter points out, it is a valuable educational experience to see the context offered by a curator’s plaque next to a work in an exhibit. When the plaque, no matter how thoughtful and informed it is, can only hope to present a partial explanation of the work, it behooves the question as to how useful a curator’s explanation can truly be. It can also be valuable for the audience when artwork is not accompanied by an explanation. When the viewer must approach art without this context, they are instead forced to come to terms with their own interpretations and preexisting knowledge.

Without an over-curated interpretation filtering the experience, the audience member is invited to bring his or her own history and experience into play. Similarly, the artist’s work is left to be as subtle (or as obvious) as it was intended. The artist’s message speaks directly to the viewer without a curator’s interpretive gloss, which can be equal parts enlightening and confusing. The resulting museum is a bit more like an ancient Greek mouseion than a modern museum: a place of contemplation and source of creative inspiration, rather than a conveyer of moral dogma.—Sophie Lewis