April 27, 2016; NPR, “Shots”

Veterans who have experienced combat are over six times more likely to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and over four times more likely to abuse their spouse or partner compared with other men. Since the violence stems from a source that differs from other intimate partner violence situations, the warning signs and circumstances surrounding the abuse differ as well.

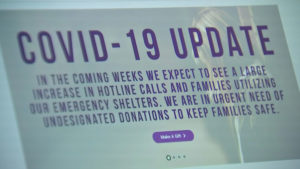

As the number of veterans returning home from multiple tours of war has grown, nonprofit organizations serving them have developed. But a gap persists when it comes to the development of programs geared to the needs of their partners and spouses who experience domestic violence.

Author Stacy Bannerman called a hotline serving military families after her husband, a former national guardsman who recently returned from his second tour of duty, abused her. Stacy’s husband experienced trauma during his tour in Iraq and developed PTSD. During their eleven-year marriage, Stacy’s husband had never before acted this way. What she also did not expect was the hotline operator’s reaction. The operator began to cry; as she explained, she had experienced so many similar phone calls.

Although many veterans suffering from PTSD are not violent, growing research suggests vets with PTSD are three times more likely to carry out intimate partner violence, according to Dr. Casey Taft, a head researcher with the Department of Veterans Affairs. They are also two to three times more likely to suffer from depression, substance abuse and unemployment. Eighty-one percent of vets suffering from depression and PTSD committed at least one violent act against their spouse or partner within the last year.

Violence committed by combat veterans often has its own distinguishing pattern that varies significantly from other intimate partner violence. Instead of the power-and-control cycle of other abusive relationships, veteran interpersonal violence tends to involve only one or two “extremely violent and frightening episodes that quickly precipitate treatment seeking.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Families seeking treatment face multiple challenges. One of the most prominent is that the services the families depend on are focused on the individual needs of the veterans, not their families. Additionally, many nonprofits serving vets’ families often ignore intimate partner violence, and organizations serving intimate partner violence survivors do not have the expertise to serve veterans’ families.

One organization with a program created by vets for vets is the Domestic Abuse Project’s (DAP) Change Step program. Change Step integrated the military culture and language into the proven mainstream curriculum. It addresses the specific issues combat vets experience, including multiple deployments and PTSD.

Spouses and partners seeking to leave abusive vets also face barriers. Often, they are caregivers; the family receives income from the VA for their services, and once they leave, this income stream disappears. Additionally, many vets would be unfavorably discharged and lose their benefits if the abuse were reported.

Stacy has a long history of supporting other military families. She is the author of When the War Came Home: The Inside Story of Reservists and the Families They Leave Behind (2006). Her newest book, Homefront 911, describes how war destroys military families. She fought for the Military Family Leave Act of 2009 and received the Patriotic Employer Award and the Above & Beyond Award from the Employer Support of the Guard & Reserve.

Bannerman is currently fighting for introduction of the Kristy Huddleston Act in Congress. The Act is named after Stacy’s friend and fellow military wife. Kristy was a nurse and worked for the VA before she was murdered by her husband, a U.S. Marine combat vet who served three tours of duty in 2012. The proposed legislation, if a sponsor can be found to introduce it and it is subsequently passed by Congress, would provide financial support to military wives and their children when a service-member is found guilty of domestic abuse.—Gayle Nelson