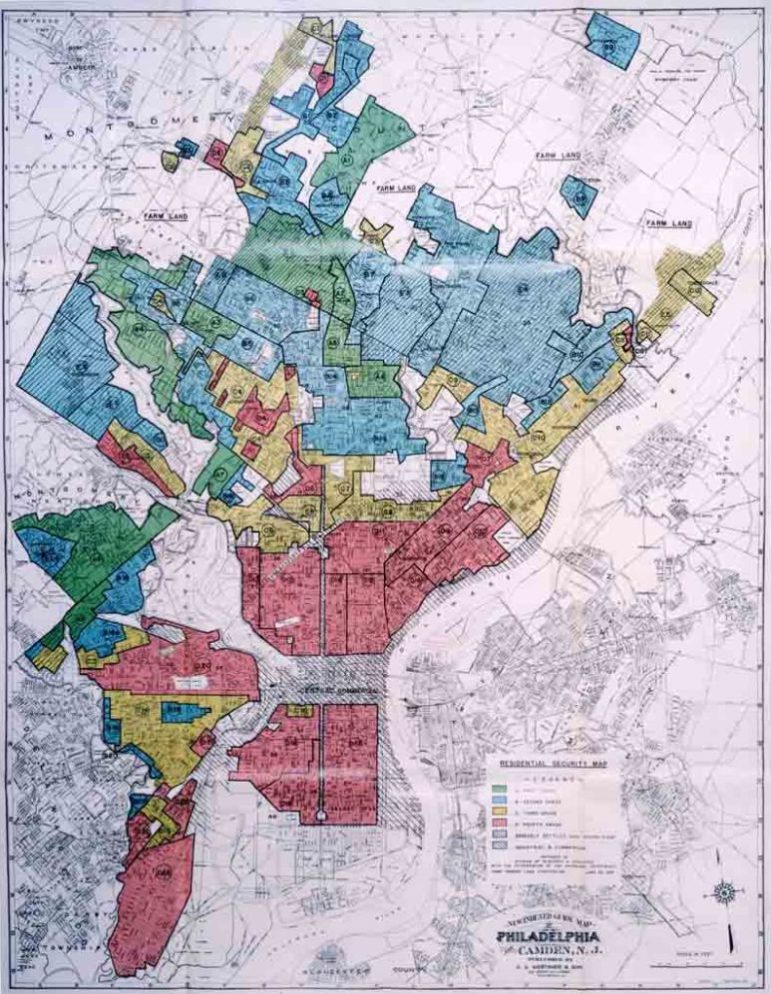

A collection of maps and documents on a website called Mapping Inequality traces the ugly history of redlining in the United States.

The materials come from the archives of the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a federal program established during the Great Depression. The purpose of the HOLC was to determine the investment risks in various cities for use by banks in making loans, but its judgments were informed by local real estate agents and lenders who, in many cases, used race, ethnicity, and poverty as proxies for investment risk. This led to neighborhoods that were lower-income or populated by minority and newcomer populations getting worse risk ratings. These were colored red on the maps—hence the term, “redlining.”

In Miami, local assessors working for HOLC described the detrimental influences on one neighborhood as: “Close to dump and Negro area.” In an area near downtown Portland, Oregon, the downsides included “infiltration of subversive racial elements.”

According to this article, historians still argue over whether HOLC actually caused housing discrimination or simply reflected already discriminatory practices. Still, the artifacts themselves are a stark reminder of how systemic racism is reinforced. Nathan Connolly, an urban historian at Johns Hopkins University who has been involved with getting the maps digitalized and online, says that the neighborhoods that were redlined by HOLC didn’t necessarily have high mortgage default rates to begin with, but by redlining areas, the agency essentially ensured that homeowners who got in trouble during the Depression would not get access to a bailout.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“It became a self-fulfilling prophecy,” Connolly said. “These residential decisions had decades-long consequences. So much of the wealth inequality that exists in America is driven by inequality in real estate market and the ability to generate equity and pass it down from one generation to the next.”

As a result of redlining, many African Americans had to rent housing, often at exorbitant rates, from landlords who knew they had no choice. And people in white neighborhoods often tried to protect their property values by adding so-called restrictive covenants to real estate contracts.

“These are agreements that say, ‘OK, we’ll sell you this house on the condition that you’re never going to build a barn on the property, you’re never going to build a liquor store, and you’re never going to sell it to black people,’” Connolly says.

You may be able to research your own city on the Mapping Inequality website, where a gadget allows you to see the modern street grid underneath. These maps and documents had been available previously at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, but this site makes it possible for activists to research the social history of their neighborhoods. When it comes to understanding and explaining the dynamics of our economies, that is a very good thing.—Ruth McCambridge