May 10, 2017; AP via Washington Post

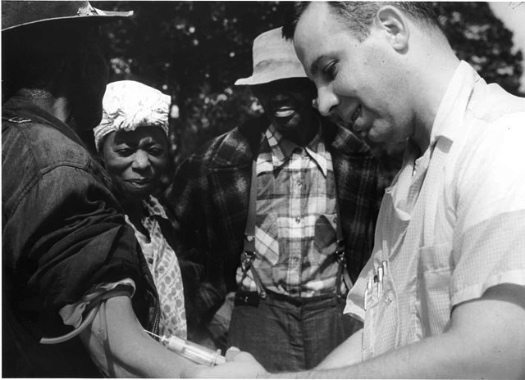

The Tuskegee Experiment, where government doctors enrolled black men in the South unwittingly for a medical trial that left their syphilis untreated “so doctors could track the ravages of the horrid illness and dissect their bodies afterward,” may seem like a story of bygone time, but its legacy is still with us today as federal courts consider what to do with the “unclaimed settlement money that still sits in court-controlled accounts.”

Syphilis is a highly contagious infection spread through sexual contact that can cause “blindness, deafness, deterioration of bones, teeth and the central nervous system, insanity, heart disease and death.” The Tuskegee Experiment, officially called “The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male,” was led by the U.S. Public Health Service in Tuskegee, Alabama, “an area which had the highest syphilis rate in the nation at that time,” with 35 percent of residents of reproductive age affected.

“For decades, the study has been widely blamed for distrust among U.S. blacks toward the medical community, particularly clinical trials and other tests. In medical and public health circles, it’s known as the ‘Tuskegee effect.’” In observance of the 45th anniversary of Associated Press reporter Jean Heller’s groundbreaking story, the AP republished her original report, where she writes,

When the study began, the discovery of penicillin as a cure for syphilis was still 10 years away and the general availability of the drug was 15 years away. Treatment in the 1930s consisted primarily of doses of arsenic and mercury.

When the study began, the discovery of penicillin as a cure for syphilis was still 10 years away and the general availability of the drug was 15 years away. Treatment in the 1930s consisted primarily of doses of arsenic and mercury.

Of the 600 original participants in the study, one third showed no signs having syphilis; the others had the disease. According to PHS data, half the men with syphilis were given the arsenic-mercury treatment, but the other half, about 200 men, received no treatment for syphilis at all… even after penicillin was discovered as a cure for syphilis.

[…]

Men were persuaded to participate by promises of free transportation to and from hospitals, free hot lunches, free medical treatment for ailments other than syphilis and free burial.

None of the men consented to the study, as doctors hid the study’s true purpose from them. The true motive of the study was finally revealed in July 1972, 40 years after the study began in 1932, when the Associated Press story “caused a public outcry that led the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs to appoint an Ad Hoc Advisory Panel to review the study.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website, which outlines the story in a matter-of-fact tone, as if federal public health officials had nothing to do with it, writes

The advisory panel concluded that the Tuskegee Study was “ethically unjustified”–the knowledge gained was sparse when compared with the risks the study posed for its subjects. In October 1972, the panel advised stopping the study at once.

The lawsuit was initiated by Fred David Gray, a “a nationally recognized civil rights attorney, celebrated lecturer, successful author, and former legislator,” after Charlie Pollard, a farmer and community leader who “was among the men in the study.”

The case was settled out of court in 1974 when the U.S. government provided $10 million and established the Tuskegee Health Benefit Program “to give lifetime medical benefits and burial services to all living participants.”

Settlement funds were used for decades to compensate study participants and more than 9,000 of their relatives. Court workers were unable to locate other descendants, and some never responded to letters from the clerk’s office, which disbursed millions before the last payment was recorded in 2008.

[…]

Payments to men and their heirs differed based on whether men were infected or were in the control group, whether they were dead or alive. Living participants who had syphilis got $37,500; heirs of deceased members of the control group received $5,000.

Though “the last man involved in the syphilis study died in 2004,” some of that settlement money still sits in court-controlled accounts. “Court officials will not say how much money is left, but documents indicate the balance is mostly interest earnings from money first paid by the government decades ago. Gray said he’s heard it’s less than $100,000.”

The government thinks it should keep the money. Some family members said the money should go towards medical screenings for the remaining family members because there is still “a small chance that syphilis dating back to the years of the study could still be in the bloodlines of families who are unaware of their connection to the study. Other family members “want a long-discussed memorial at the old hospital where the study was run at Tuskegee University.” Gray also has a request in to U.S. District Judge Myron Thompson “to use the remaining money to fund operation of the Tuskegee Human and Civil Rights Multicultural Center, a combination museum and town welcome center that includes a display about the syphilis study.”

Though “relatives of the men still struggle with the stigma of being linked to the experiment,” Gray told descendants that “the men of the study…wanted a lasting memorial to their legacy.”—Cyndi Suarez