June 17, 2018; Washington Post and the New York Times

On the lower rungs of the economic ladder, the benefits promised by a growing economy, a tight labor market, and a large tax cut have yet to trickle down. If anything, life has gotten harder, not easier, for many. Is this just a matter of timing, or does it reflect significant structural changes in our economy? The former means patience is the best response; the latter requires difficult policy debate in search of solutions.

Last week, the Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics released its monthly report on what American workers earned. Production and nonsupervisory workers, representing about 80 percent of nongovernmental workers, earned less than they had one year earlier: “From May 2017 to May 2018, real average hourly earnings decreased 0.1 percent, seasonally adjusted.” Many of these workers are in the factories and foundries, in industries the current presidential administration has said its policies were designed to benefit. Many others are service workers, a category that has seen rapid growth in numbers if not in earnings.

This is not supposed to happen in a tight job market and with an economy that has continued to grow month by month, particularly with the promised injection of wage vitality from the recent tax cut. Supporters of the administration’s policies say we need to just be a bit more patient. DJ Nordquist, chief of staff for the Council of Economic Advisers, reminds the Washington Post that “the law is just six months old. Our estimates [of the tax law’s benefits] were for ‘steady state’—when the full effects of the law spread throughout the economy, which will take years, as we always said it would.” For Stephen Moore, a conservative economist at the Heritage Foundation and campaign adviser to President Trump, the data is a sign of health and an indicator of better times to come. He told the Post that “the drop in real wages could be a reflection of the economy adding low-end jobs, rather than declining values further up the chain. If so, he said, that would be a sign of economic vitality, as the economy pulled in unemployed workers.”

But perhaps the problems are cracks in our economic fabric that we have yet to address. Could the lack of economic improvement for so many workers may, as critics of trickle-down economics say, reflect the growth of large businesses at the expense of smaller companies and reduced the power of organized labor?

Over just a few decades, larger employers have rapidly grown at the expense of smaller companies, as David Leonhardt notes in his New York Times column:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The hardware store has given way to The Home Depot. The local hospital and bank are owned by a chain. The supermarket is Whole Foods, which is now owned by Amazon. The family-owned manufacturer may simply be out of business. The share of Americans working for small companies fell to 27.4 percent in 2014, the most recent year for which data exists, down from 32.4 in 1989…Today, companies with at least 10,000 workers employ more people than companies with fewer than 50 workers.

At the same time, many larger employers no longer face unions that once might have checked their power and resources. Since 1983, the portion of the work force that is unionized has fallen in half, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. Further, about half of union workers (7.2 of 14.8 million total) are working in government. With less power comes less ability to demand better wages and working conditions.

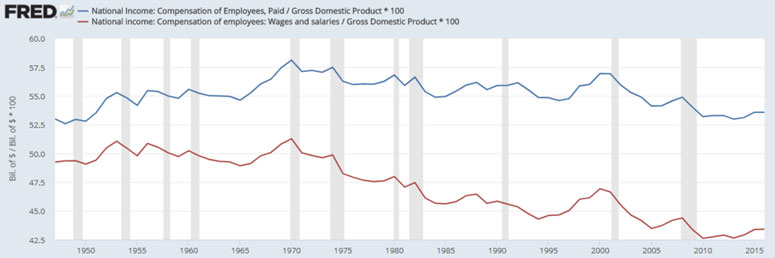

What appears to be a tight job market may also mask a significant change in the structure of our economy that holds real earnings down. The lack of jobs that pay good wages to those with less education has led a significant number of males to stop looking for work and, thus, no longer be counted as unemployed. Citing the work of Harvard Economists Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz, N. Gregory Mankiw observed in a New York Times column that “the tendency for advances in technology to enhance the productivity and wages of workers who have certain skills while reducing the demand for those who don’t. Unskilled workers are left with the choice of accepting lower wages or leaving the labor force. This hypothesis is consistent with the fact that labor force participation has fallen more for workers with lower levels of educational attainment.” Large organizations may prefer to spend their capital on new and improved technologies rather than paying their workers more. As a result, not only have hourly earnings stagnated, but the share of income going to the workforce has declined and the wealth of the richest part of our society has grown and grown.

Beyond the size of a worker’s check and the pain of its decreasing purchasing power, these changes affect the nature of our communities and the glue that holds them together. US Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA) told Leonhardt, “This has been a blind spot for the last 20, 30 years. One of the things that people are rebelling against in this country is large, growing institutions. People feel that individuals don’t control their destiny.”

Nonprofit organizations big and small have a large stake in this debate. For their clients and their communities, the impact of a stagnating economy is personal and may place increased service demands to directly fall on the nonprofit sector. For example, a few years ago, Ohio determined that 15 percent of state Walmart workers or 7,000 total, were receiving SNAP benefits (food stamps). If those who see the current malaise as structural are correct, advocacy efforts need to grow to support needed policy changes.—Martin Levine