November 5, 2018; Arkansas Times

A controversial Arkansas Medicaid work requirement went into effect June 1st, with the stipulation from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) that the state’s Department of Human Services (DHS) must commission an independent evaluation to measure if the policy is meeting its goals. Nonetheless, according to the Arkansas Times, the state has not even begun to search for an evaluator.

The Arkansas DHS claims the delay is the result of the failure of CMS to approve its evaluation plan. CMS sent DHS a letter November 1st, writes reporter Benjamin Hardy, stating that the proposed evaluation design “should be better articulated and strengthened.”

Arkansas is the only state thus far that has implemented a work requirement for Medicaid beneficiaries. Those between the ages of 19 and 49 who are not otherwise exempt (e.g., unable to work because of illness, disability, or parenting responsibilities) must verify engaging in 80 hours of work activities each month. If a beneficiary does not report his or her work activities—or an exemption—over a three-month period, they are dropped from the Medicaid program and cannot get health coverage for the remainder of the calendar year. In September and October, the Arkansas Times reports, 8,500 beneficiaries lost their coverage.

The majority of beneficiaries are exempt from the work requirements. The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) has been tracking the percentage of beneficiaries required to comply, along with rates of compliance. In the fourth month of implementation, CBPP data show 72 percent of beneficiaries were found by the state to be exempt, 3 percent filed claims for exemption, 2 percent fulfilled the work requirements and 23 percent failed to satisfy the reporting requirement.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

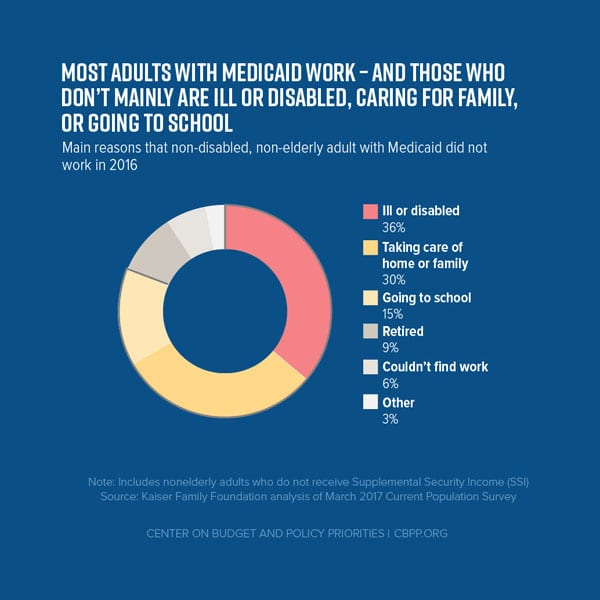

In other words, more than 80 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries who the state thinks should be reporting their work to the state are not. But who is at fault here? Research shows that most Medicaid beneficiaries who are able to work actually do work. The challenge for these low-income people is complying with the reporting requirements. As NPQ’s Carol Levine wrote earlier this fall:

Many in Arkansas are losing healthcare coverage due to this program. Not because they are not meeting the work requirement—in most cases, they are working, and were working before this program went into effect. Rather, they are losing Medicaid because they did not receive notification of this requirement, failed to open their mail, moved, or lacked access to a cellphone or computer to report their hours online. In other words, as the research finds on this tired retread of a program, they are besieged with more red tape in pursuit of nothing but reinforcement of a narrative about the idle poor.

The state’s proposed evaluation plan does not address this. Nor does it test the basic hypothesis that work requirements—by pushing people into the workforce—will improve health. Instead, it focuses on three tangential questions: “Whether or not work requirements ‘promote personal responsibility and work,’ ‘encourage movement up the economic ladder,’ and ‘facilitate transitions’ from Medicaid to other types of insurance.”

Judy Solomon from CBPP pointed out to the Arkansas Times that the draft proposal “doesn’t even raise the question of, ‘Well maybe if we’re taking coverage away from people, it’s going to make them less able to work, or it’s going to make them less healthy.’” As she notes, the state is looking at the program as a work program, not a health program.

CMS also criticized the plan for having no comparison control groups. In the letter to the state, the agency encouraged DHS to “develop a longitudinal survey to track former beneficiaries ‘for several years’ so as to ‘understand employment, income health status, and coverage transitions over time.’”

Though she disagrees with the CMS decision to give Arkansas a waiver to test work requirements in the Medicaid program, Solomon noted that she wasn’t surprised that the evaluation plan was not approved. “[CMS does] seem to at least have some seriousness about…having evaluations that make sense,” she said.—Karen Kahn