Lester Salamon, who directs the Center for Civil Society at Johns Hopkins University, has charted the evolution of the nonprofit sector since the 1980s. Many years ago, Salamon noted, as NPQ put it back in 2002, “that nonprofit America has shown a remarkable, although little-recognized, talent for responding to an environment of rapid change—he calls this resiliency.”

Always guided by evidence, however, Salamon has also always noted that this resiliency cannot be taken for granted. The latest report from the Center, authored by Salamon and Chelsea Newhouse, is titled The 2019 Nonprofit Employment Report and accomplishes the rare feat of being both heavily data-driven and accessible. One can quibble with some data choices—why look at nonprofit employment as a percentage of private sector employment, rather than as a percentage of total employment, for instance? Still, the report provides a fascinating overview of the scale and the scope of the nonprofit sector, as well as identifying some key challenges.

The report, note Salamon and Newhouse, is based on data generated through the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, a database that “encompasses 97 percent of nonfarm employment, providing a virtual census of employees and their wages as well as the most complete universe of employment and wage data, by industry, at the State, regional, and county levels.” The most recent year available in the data is 2016; the report covers the period spanning from 2007 to 2016.

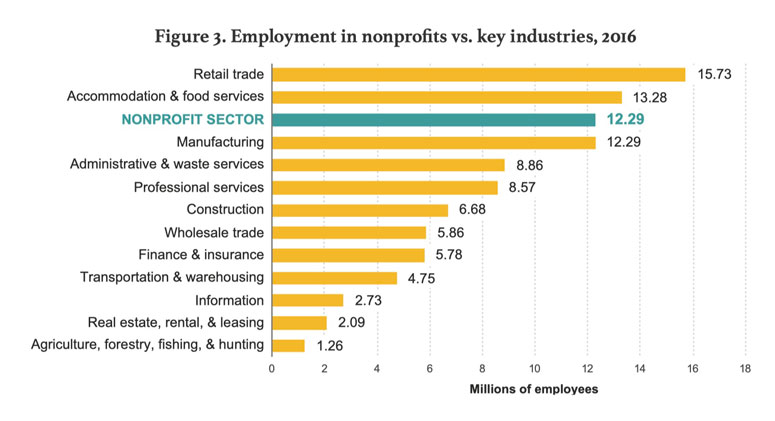

The report finds that nonprofits employed 12.29 million workers in the US in 2016. This works out to 10.2 percent of the US private sector employment and roughly 8.1 percent of the over 152 million Americans (including public sector workers) employed at the time. How many workers is 12.29 million? Well, Salamon and Newhouse note that the US nonprofit workforce in 2016 was as large, maybe marginally larger, than the country’s entire manufacturing workforce. The fate of manufacturing, of course, was a major 2016 election theme. How often did you hear in that campaign about the state of the nonprofit workforce? We at NPQ are guessing not so often.

Nonprofits also employ nearly twice as many workers as construction (6.68 million), more than twice as many workers as finance and insurance (5.78 million) or transportation (4.75 million), and almost six times as many as real estate (2.09 million). If the nonprofit sector were treated as a single industry, it would be the third-largest generator of payroll income in the US, generating total salaries in 2016 of $638.08 billion.

How is employment in the nonprofit sector distributed? Hospitals are the single largest employer —34 percent of the total, with other health care sectors (e.g., nursing homes and health clinics) an additional 21 percent. Education is another 14 percent. Social services are 12 percent. Salamon and Newhouse add that nonprofits account for roughly one sixth (16 percent) of total education employment and roughly two thirds (66 percent) of total hospital employment.

One interesting report finding is that, within their industries, nonprofit workers typically out-earn their for-profit brethren, as this figure shows:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

For instance, an average nonprofit worker in ambulatory health earns $1,364 a week versus $1,101 for a person employed in the same industry by a for-profit firm. That is a 24 percent nonprofit wage advantage. In the social assistance sector, the nonprofit wage advantage is a stunning 55 percent ($552 a week for nonprofit wages versus $356 a week for a person employed by a for-profit firm). In other sectors, the nonprofit wage advantage is less—in hospitals, it is 14 percent; in nursing homes, four percent. But nonprofit workers outpace for-profit employee compensation in every sector measured except arts and recreation.

Nonprofits have also outpaced for-profits in employment growth. From 2007 to 2016, the number of employees in nonprofit firms increased 16.7 percent, while employment in for-profit firms rose only 4.6 percent. A key difference is that nonprofits are less impacted by recessions than for-profit firms—that famed nonprofit resiliency rises again. Between 2007 and 2012, nonprofit employment rose 8.5 percent while it fell 4.1 percent for for-profits. From 2012 to 2016, for-profits grew faster than nonprofits (9.1 percent versus 7.6 percent for nonprofits), but this slight gain hardly made up for the loss of for-profit sector jobs during the Great Recession.

So, is all well in Nonprofit-land? Well, not exactly. Salamon and Newhouse note that for-profits are making inroads in a number of traditional nonprofit sectors. As they explain:

- While nonprofit employment in the nursing and residential care field grew by

1 percent between 2007 and 2012, for-profit employment in this field grew by nearly 11 percent. - In the hospital field, for-profit employment growth outpaced nonprofit employment growth 10.2 percent to 5.3 percent.

- In social assistance, for-profit employment growth outpaced nonprofit growth roughly 20 percent to 8.4 percent.

- And in the education field, the for-profit edge was 25 percent to barely 10 percent.

How are nonprofits being outpaced by for-profits in core fields yet still growing faster than the private sector as a whole? It may seem like a paradox, but it really has to do with the fact that the sectors where nonprofits are located (i.e., services) are growing faster than the economy as a whole. As result, nonprofits are both becoming a larger part of the economy, even as they are losing market share in some key sectors.

Near the end of the report, Salamon and Newhouse make a few key observations:

- The data demonstrate the “significant job creation potential of the nonprofit sector, especially during recessions.”

- Nonprofits need to pay attention to job creation efforts that rely on income tax deductions; of course, the value of a business tax deduction to a nonprofit is zero. Thus, incentives given in the form of tax breaks can disadvantage nonprofits.

- Nonprofits need to pay attention to public procurement because if government contracting is just based on lowest price, this will “squeeze out some of the major features that make nonprofits special, such as their community-building activities.”

- Expanded efforts are needed to help nonprofits overcome structural impediments to raising capital (of course, there is no equity stake to give), which can be accomplished through such credit enhancements as interest subsidies and loan guarantees.

Salamon and Newhouse conclude, with a bit of a warning. “To date,” they write, “the sector has shown remarkable resilience in the face of significant economic pressures and competitive challenge. With pubic funding under siege and private resources strained, however, the nonprofit job engine is under increasing pressure, with clear evidence of loss of market share in crucial fields.” The message to nonprofit advocates is clear: Attention must be paid not only to the charitable deduction, but to such factors as government contracting, incentives, and capital markets that can directly impact their business models.