March 8, 2019; Aeon

In light of the scandal in university admissions that broke on Tuesday, this article by Clifton Mark on all of the fallacies embedded in our attachment to the notion of meritocracy should have particular resonance. The article came out last week but perhaps can be used to capture a fuller set of learnings from the admissions scandal. The title of the piece is, “A belief in meritocracy is not only false: it’s bad for you.”

Mark makes the case through research that a belief in meritocracy is part and parcel of the rags-to-riches story central to our public consciousness and is responsible for having driven a lot of badly focused social policy.

The university admissions scandal involves rich people buying their children’s way into prestigious universities, a practice that, let’s face it, has been going on for years in many guises. Students without money and their parents regularly compete against such legacies, but we have retained a belief that if one simply works hard enough, one will reap the benefits in relation to effort and smarts. The fact that the statistics do not support this does not matter as much as the fact that we can always find a story that does, haunted as we are by Horatio Alger. We certainly don’t need to eschew hard work and learning as values, but it is not the equalizer that many still hope it will be.

Mark writes, “The most common metaphor is the ‘even playing field’ upon which players can rise to the position that fits their merit. Conceptually and morally, meritocracy is presented as the opposite of systems such as hereditary aristocracy, in which one’s social position is determined by the lottery of birth. Under meritocracy, wealth and advantage are merit’s rightful compensation, not the fortuitous windfall of external events.”

He notes that a 2016 study from the Brookings Institution found that 69 percent of Americans believe that people are rewarded for intelligence and skill. This downplays external factors like luck and a wealthy family which can, for instance, buy a child’s way into a top-notch school.

Mark believes that “the link between merit and outcome is tenuous and indirect at best” and that a growing body of research in psychology and neuroscience indicates that believing in meritocracy “makes people more selfish, less self-critical, and even more prone to acting in discriminatory ways.”

Perhaps more disturbing, simply holding meritocracy as a value seems to promote discriminatory behavior. The management scholar Emilio Castilla at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the sociologist Stephen Benard at Indiana University studied attempts to implement meritocratic practices, such as performance-based compensation in private companies. They found that, in companies that explicitly held meritocracy as a core value, managers assigned greater rewards to male employees over female employees with identical performance evaluations. This preference disappeared where meritocracy was not explicitly adopted as a value.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Now, maybe we should pause for a moment and think about how stuck our civil society practices are before considering this next statement.

“Meritocracy,” Mark writes, “is the most self-congratulatory of distribution principles. Its ideological alchemy transmutes property into praise, material inequality into personal superiority. It licenses the rich and powerful to view themselves as productive geniuses.”

And our buying into such stuff creates a lock on social systems partially of our own making. Many of those devising social theories that drive policy have skin in the game.

This is why debates over the extent to which particular individuals are “self-made” and over the effects of various forms of “privilege” can get so hot-tempered. These arguments are not just about who gets to have what; it’s about how much “credit” people can take for what they have, about what their successes allow them to believe about their inner qualities. That is why, under the assumption of meritocracy, the very notion that personal success is the result of “luck” can be insulting. To acknowledge the influence of external factors seems to downplay or deny the existence of individual merit.

Back in 2007, writing on the CitizenPost blog, Cynthia Gibson brought this home to the leadership patterns in the nonprofit and philanthropic sector—which, she says, seem too often obsessed with credentials, eclipsing the real merit and intelligence in our ranks, earned through hard experience and study. She ends her piece with the following:

So what do we do about it? We can start by recognizing that a cultural obsession with last names, pedigree, and/or social capital doesn’t have to be one that we embrace, but rather, challenge. We can hire people on the basis of their experiences and skills, rather than on who their parents are or where they went to school. In the midst of all the accolades being bestowed on our leaders, we can ask, “what have they actually done to deserve these?” And, perhaps most importantly, we can ask what obstacles, if any, has this person endured or overcome and how has that made them a stronger, smarter, and/or ethical person?

As Booker T. Washington once wrote, “Success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he has overcome.” Perhaps that’s the criteria we should think about using for “the best and brightest” in the nonprofit sector.

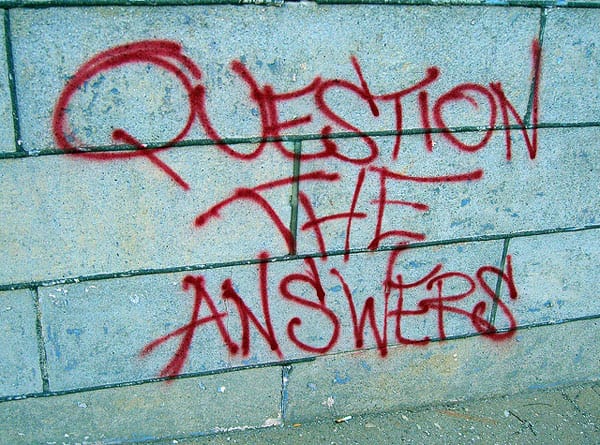

It is time to interrogate some of the metanarratives we have built over time. As silent designers of failed social policy and supporters of the stagnating landscape of sectoral leadership, they can create enormous delays to real progress on social and economic equity.—Ruth McCambridge