Hospitals offer unique windows into society. Their proximity to and interactions with the populations they serve provide insights into health disparities, revealing how lived experiences in disparate environments affect health. Urban safety-net hospitals offer even more unique insights into populations, places, and health. Such hospitals, including the one in which we work, Boston Medical Center (BMC), are often located in low-income neighborhoods and serve largely BIPOC populations. They are regularly challenged to provide high quality care with limited resources.

Our hospital, for example, is much more likely than other hospitals to care for the uninsured or those who have limited Medicaid coverage. In our work, we experience the intersectionality of health and wealth every day. Daily, we see in our patients how individuals’ economic positionality converges with economic structures, predictably determining who thrives and reaches their full potential, and who does not.

Boston, like many urban areas around the country, has a deep history of racism and segregation. Consistent with the legacy of redlining, new research shows that racist real estate and housing practices continue to perpetuate wealth differences across races. In 2015, the Boston Federal Reserve Bank released the Color of Wealth report, which highlighted the widening wealth gap between white and nonwhite people. The report stated that millions of BIPOC individuals don’t have enough assets to pass down to future generations. Meanwhile, white Bostonians are more likely to own every type of liquid asset than Black and Latinx Bostonians. “White households have a median net worth of $247,500, while Dominicans and U.S. Blacks have a median wealth close to zero. Out of the nonwhite households, Caribbean blacks have the highest median net worth with $12,000, which is only five percent of the wealth credited to white families.”

In Boston, as in most US metropolitan areas, BIPOC communities are disproportionately served by certain medical centers. A few years ago, the Boston Globe reported that, “When looked at citywide, the data show that Black Bostonians are more than three times as likely to get care at Boston Medical Center.” Though other academic medical centers also serve large BIPOC populations, at Boston Medical Center (BMC) our safety net hospital status and physical location within these segregated communities bear unique witness every day in how these race-based wealth differences impact disease morbidity and mortality.

Given longstanding trust issues between health providers and BIPOC communities—the product in significant part of decades of misinformation and/or lack of information—safety-net hospitals can serve as bridges between healthcare providers and marginalized communities while supporting such communities’ existing assets and strengths. But doing so requires more than medical intervention. It requires an all-encompassing approach that focuses not just on the provision of excellent medical care, but also on innovative ways to address inequities by engaging and building partnerships with community groups and strengthening collaborations with residents.

Given this reality, it was natural for BMC healthcare workers—who sit on the front lines and regularly witness the effects of economic exclusion on their patients—to look to place-based and systemic change solutions to solve the health problems of the communities we serve.

The Twin Pandemics: COVID-19 and Structural Racism

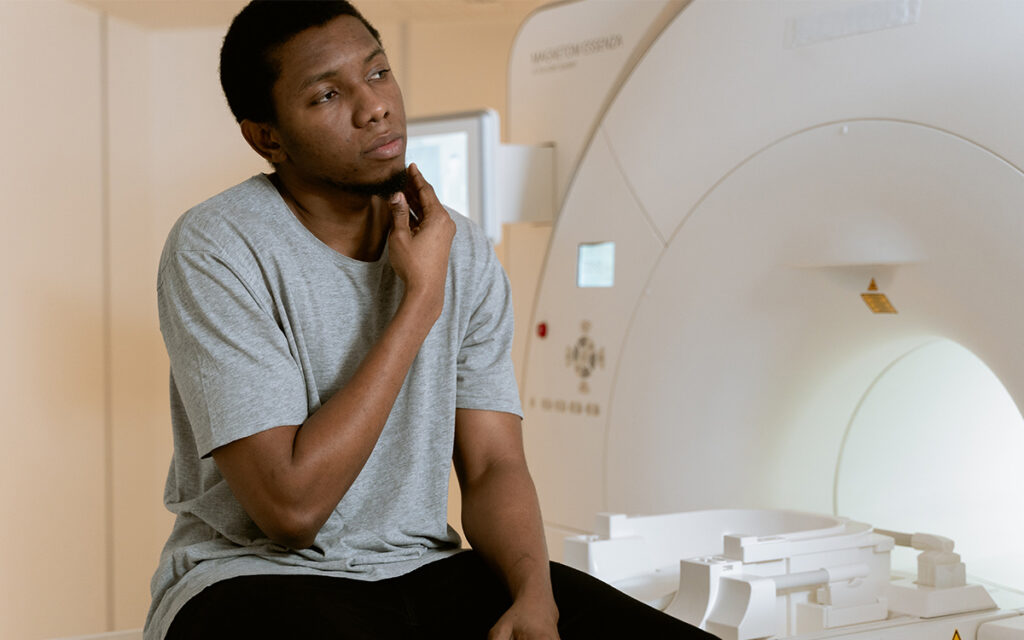

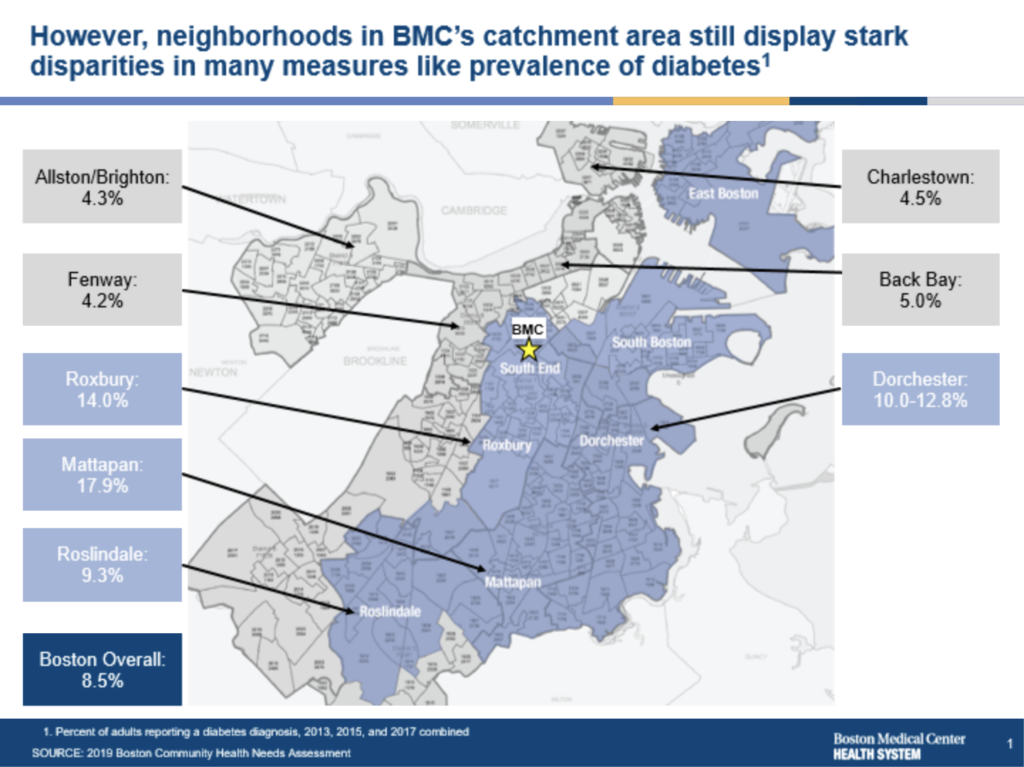

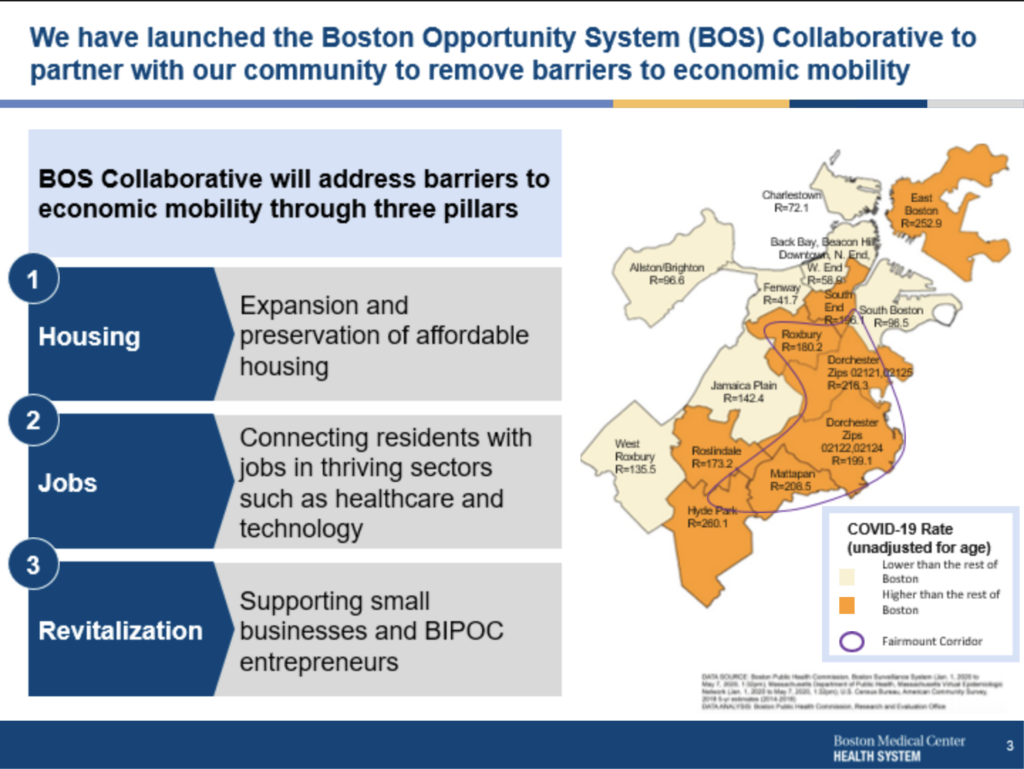

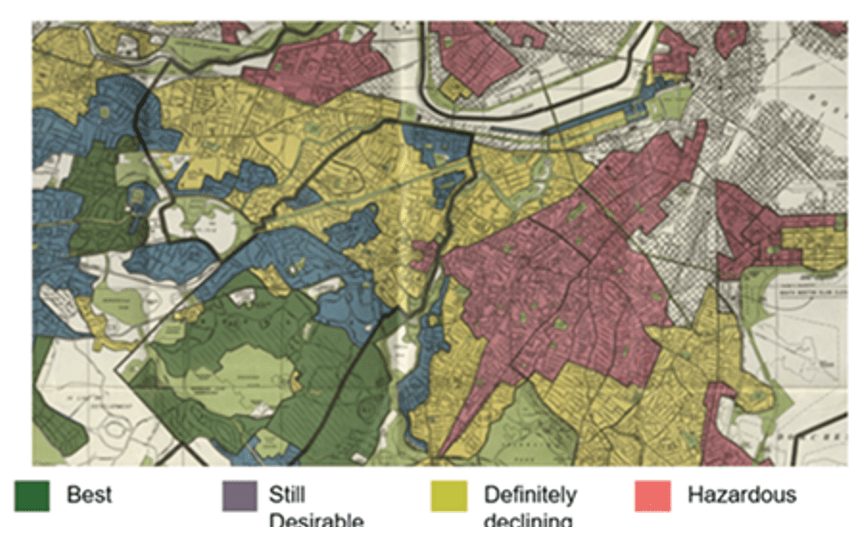

In addition to the prevalent racial wealth gap, the COVID-19 pandemic revealed how specific patterns of morbidity and mortality disproportionately affect BIPOC communities. As the maps in figures 1A through 1D demonstrate below,1 areas with the most prevalent wealth gaps also have high rates of diabetes and homicide by firearm incidents, were COVID 19 infection hot spots, and share a history of redlining (along with ongoing structural racism in the housing market). These problematic patterns are ripe for disruption.

In 2020, former Boston mayor (and current US labor secretary) Marty Walsh issued a statement declaring racism to be “an emergency and a public health crisis.” Walsh’s declaration recognizes the obvious links between health inequities and the enormous racial wealth gap noted above. We see these links in our own work.

Within safety net healthcare institutions, effective healthcare provision cannot focus solely on the services and resources offered to patients and communities once disease has occurred. Rather, healthcare institutions must be proactive in preventing morbidity and mortality by focusing on and mitigating the root causes of illness and death. While a health center alone might not have the power to eradicate the health disparities that persist in disinvested neighborhoods, safety-net hospitals and community health centers can play a critical leadership role in tackling the upstream antecedents of health inequity head-on. As trusted community providers known for clinical and academic excellence, safety net institutions must harness their unique location in the healthcare landscape to forge an effective path towards addressing wealth-based health inequities.

Finding a New Path for Innovation: One Example

In December 2017, BMC consolidated its campus with the aim of better serving the community and decreasing its carbon footprint. To address the structural racism that leads to the racial health divide illustrated above, BMC also agreed to invest $6.5 million over a period of five years in an affordable housing initiative.

This initial venture into place-based investing quickly attracted other health providers that recognize the link between housing stability and health outcomes: three healthcare anchor institutions—BMC, Boston Children’s Hospital, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital—chose to work together for mutual benefit, pooling $3 million that was invested into the Innovative Stable Housing Initiative (ISHI), with funds directed to flexible and upstream policy solutions for housing.

With this momentum, and with an initial investment from the JPMorgan Chase foundation’s Advancing Cities Challenge competition, BMC formed the Boston Opportunity Systems (BOS) Collaborative in 2020. The collaborative takes a community-driven, systems-change approach to its work, focusing on creating new pathways to employment and new affordable housing options for people in Boston’s historically disinvested neighborhoods.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Can’t Go Back: The Time for Economic Inclusion Is Now

“We need something tangible, we need a win—we’ve been talking about this for too long.”

John Smith, Executive Director, Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative

One of the key community-based organizations leading the BOS Collaborative alongside BMC is the BIPOC-led Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI), which over the course of its 35-year-plus history has evolved into building community land trusts, fostering community engagement, and developing homes and businesses in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston, all without furthering displacement. At BMC, we have learned that partnering with BIPOC-led grassroots organizations such as DSNI enables new investments in community land trusts and BIPOC businesses. Such investments—supported by patient (long-term), non-extractive (low-interest, flexible repayment) capital—is critical to forestalling gentrification in Boston’s BIPOC communities.

Putting Economic Inclusion into Action as Health Equity

“Leveraging healthcare investments to improve the health and well-being of our people, our communities, and our economy is eminently possible. The models for how to do it already exist.”

Dana Brown, “Healthcare as a Public Service: Redesigning U.S. Healthcare with Health and Equity at the Center,” NPQ, January 2022

As Smith from DSNI reminds us, talk is cheap; action is not. Fortunately, in Boston, there are real examples of transformative investments that are being made with strong community input, beginning to build BIPOC wealth, and staving off displacement.

One example under development is Nubian Markets in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood. In 2019, and in recognition of the links between food access and health outcomes, BMC provided an initial, zero-interest, $1 million loan to support a grocery store in Roxbury after community residents advocated for one during urban planning meetings regarding the development of the old Bartlett Station bus depot. After an extensive planning and proposal process conducted in partnership with Nuestra Comunidad, the Conservation Law Foundation, and several community development financial institutions (Massachusetts Housing Investment Corporation, Local Economic Assistance Fund), participants resolved that the grocery store’s proposed operators will become owners instead. These operators include two BIPOC men—Yusuf Yassin, owner of ASCIA Kitchen, and Ismail Samad, a nationally renowned food justice advocate and entrepreneur and co-founder of the Gleanery restaurant in Putney, Vermont. These Muslim entrepreneurs—with East African and African American roots and extensive culinary and food operation expertise—are converting a formerly small grocery store into a full-service Halal market, the first of its kind in Boston. Slated to open later this year, the new market will serve the city’s growing, vibrant Muslim community. The Islamic Society of Boston Cultural Center, the largest mosque in New England, is located nearby, and the neighborhood is home to many families of East African origin.

With continued partnership from all entities at the table, Yassin and Samad will have the opportunity to not only operate the market but also eventually own the real estate the market occupies. This opportunity is a generational game-changer that supports BIPOC wealth creation and mitigates displacement in a rapidly gentrifying section of Boston. In addition, this opportunity will yield the possibility for employees to own equity in the business. Yassin and Samad are in discussions with BMC’s procurement department to establish a partnership to defray food costs and subsidize the store’s operations. The building in which the market is located contains a large community room that provides a space for entrepreneurship and health and wellness programming, another form of community investment that likewise promises to have positive health impacts.

The financial backing by safety net academic hospitals of BIPOC businesses in such businesses’ early stages of development is a solid model of how various entities can come to the community-led table with investment dollars to support the community’s vision of BIPOC business and real estate ownership and long-term wealth creation.

The Future of Health Systems: Place-based Engines of Economic Inclusion

Given the existence of structural racism and its creation of ongoing fundamental health inequities, place-based and system-change approaches to economic inclusion are absolutely necessary for residents of historically marginalized communities to enjoy good health. Safety net academic hospitals, which are often neglected in US healthcare policy, are natural backbone organizations to work alongside grassroots groups and community development finance institutions to support financial stability and wealth creation in BIPOC communities and, in so doing, to foster good health for all.

Notes

- Figures 1A and 1B are based on community health needs assessment data from 2019. Figure 1A depicts the impact of diabetes in the neighborhoods surrounding Boston Medical Center and reflects the percentage of adults who reported a diabetes diagnosis in 2013, 2015, and 2017. Figure 1B depicts the impact of homicide by firearm in the neighborhoods surrounding Boston Medical Center. The map reflects the number of homicides by firearm rate, age-adjusted per 100,000 residents 2011-2016 combined. According to the map, Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan have the highest rates of homicide by a firearm. Figure 1C is based on multiple data sources, namely, Boston Public Health Commission, Boston Surveillance System (Jan 1, 2020, to May 7, 2020), Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Massachusetts Virtual Epidemiologic Network (Jan 1, 2020 to May 7, 2020); US Census Bureau, and the American Community Survey, 2018 5-year estimates (2014-2018). It depicts the COVID-19 transmission rate for BMC’s surrounding neighborhoods and shows that Roslindale, Hyde Park, Mattapan, Dorchester, Roxbury South End, and East Boston have had the highest transmission rates. Figure 1D is based on the Norman B. Leventhal Map Eduction Center at Boston Public Libraries. (1938). Residential Security Map of Boston, MA.