On Friday afternoon I got a call from a buddy I hadn’t spoken to in a couple of years. We met when we were 10 years old playing boys club basketball in Washington, DC. Back then, we were rivals. He had game, especially for a white boy from Upper Northwest. I wasn’t too shabby myself. As it happened, we wound up going to middle and high school together where we played alongside one another for the better part of six years. I remember spending entire weekends at his house watching and talking about basketball over pizza. We were in 9th grade when Rodney King was beaten by the LAPD, 10th when L.A. residents rebelled. We listened to the same rap albums. We dressed in similarly baggy hip-hop gear. He used to let me borrow his black Grand Cherokee to get my haircut or so I could front with a girl I was trying to impress. We were close. But I can’t recall us ever talking about race.

So when his name showed up on my phone in the middle of the day on a Friday, I didn’t know what to make of it. Why was he calling? Why now?

It turned out that he wanted to see how I was doing. “…with everything happening in the news,” he said, referring to the George Floyd protests, Chris Cooper, and COVID-19.

He said he couldn’t possibly know what I was experiencing as a black man, but that as a white man he was in turmoil. He was angry and upset. He couldn’t understand why a cop could think it was okay to take a man’s life, let alone over something so trifling as a counterfeit $20. He said he’d been following some folks of color on social who’d been challenging white people like him to do or say something. At first, he felt paralyzed. What, after all, could he do? He thought about contacting the Washington Post or some other publication, but for what, to say what? Instead, he decided to pick up the phone and call me to ask if I was good. If I needed anything. If there was anything he could do. We wound up talking for an hour or so and in that time we both started to recover parts of our relationship that had been forged more than 30 years ago when we were kids. As we talked, the conversation expanded into a broader discussion of the noxious political landscape and the price COVID-19 is exacting on black lives. He acknowledged that he was one of the privileged who retreated to summer homes to ride out the crisis, but he now worried that the isolation he and other privileged white people had sought was only deepening the disconnect between himself and the world.

The reality is that none of what is happening is surprising or shocking to me. I’m old enough now to have experienced and absorbed the pain of Rodney King’s beating in the early ’90s, Amadou Diallo’s shooting and Abner Louima’s dehumanization in the late ’90s, and the string of police killings that shocked us into the streets just a few summers ago.

To be sure, my high school buddy wasn’t the only white guy in my life to reach out over the past few days, and ours wasn’t the first conversation about COVID-19, George Floyd, and Amy and Chris Cooper that I’d had with a white male friend or colleague that week.

Earlier in the week, a white male CEO I have worked with extensively also reached out. He leads an organization that serves primarily people of color, yet he has always had a difficult time wading into race-related discussions or dealing with the issues that impact the people his organization serves through a racial justice lens. The CEO was anguished and wanted to make some kind of statement, but he didn’t know if he had a place in the conversation and was worried about coming off as inauthentic. Inasmuch as I believe that he does need to reflect on whether he’s still the right person to lead his organization going forward, the moment demanded action. And so the advice I gave him was to own his own pain. To not allow himself to get stuck in white guilt. To resist the urge to write a tired mass email expressing his sympathy. “Talk to people about how you feel. That’s what people want from you right now. We don’t need your sympathy. We need you to feel your own hurt, to express your own outrage. Tap into that,” I said to him.

Therein, though, lies the rub—I don’t know if he or many of my white male friends, most of whom are now in their 30s and 40s—have ever really allowed themselves to reflect deeply on and tap into the ways racism has and continues to harm them. As far as I can tell, you mostly see it in terms of harms that have been done exclusively to people of color. You experience black death as repugnant, but not as a visceral, perpetual threat to your own existence and violation of your humanity.

It is probably an unpopular thing to write at this moment, but I am going to do it anyway: We who do DEI and anti-racist work often say that we need white people to do their own work. We say we want y’all to stop asking us to do your emotional labor (in fact the CEO was asking me to do that very thing for free no less though I am sure he didn’t realize it). But the truth of the matter is that I don’t know if we offer much insight into what we mean or how you could go about beginning that work. In recent days an excellent article about supporting black people at work has been making the rounds to my white male friends. Some of you have even sent it to me, which is ironic but whatever. That’s a start. But that’s all it is—a start.

And so, I am issuing this challenge to my white male friends. I love y’all and I have never asked much of our friendship. Never made things weird or uncomfortable for you. Never asked you to read books by black authors, especially black women like Audre Lorde or Toni Morrison. Never asked you to support black candidates or black businesses or black issues. I have always strived to be open-minded and levelheaded about racial issues. I have entertained many liberal notions about meritocracy and opportunity—that it’s about class, not race, or that opportunity and access are the keys—that in my heart I have never fully bought into because my experience has shown me otherwise. I rarely talk about the racist traumas I have experienced with the police or in the workplace. On a few occasions, I’ve held my tongue or softened my message to maintain our relationship. When you said something that could be interpreted by someone who doesn’t know and love you as racist or uninformed, I’ve either quietly let it ride or found a tactful way to restate what I thought you meant. And I have done all of that because our friendship has meant and continues to mean so much to me. And because I believe cross racial relationships are critical to our survival and healing both as humans and as a nation.

Now I come to you with an ask that is as much for me as for you.

I’ve been aware of the precarious identity I hold as a black man in America since forever. A cop put his gun to my throat when I was in high school. In college, I stood trial on a charge of inciting a riot because a cop lied on me. In law school, I was beaten and thrown in jail by a gang of cops because I didn’t get down on my knees fast enough. I share my social location at the time of these trying incidents because I was doing all of the things I was told I needed to do in order to avoid the police, yet they happened anyway.

All of those experiences and more live in my body. Even now, I find my heart beats faster and my mind starts to scramble whenever I recall those encounters. I am scarred and I am angry. I am angry that I have been scarred by other people’s sickness. I have had to devote much of my life to thinking and talking about racism just so I don’t go crazy. Years of my life that could have been devoted to hobbies and other career pursuits have been bogged down with a fight to root out an injustice that I didn’t create but feel obligated to address. And while I’ve done a lot of work to push through and past those experiences, some of which were nearly three decades ago, they will always haunt me. Even now, each time I witness or learn about another horrific event, my own traumas risk resurfacing again. That is my reality. I live with it.

What I ask of you is that you don’t turn away from the pain you are witnessing in this moment. Don’t bury yourself in work or how the markets are doing. Don’t tell yourself there are more important things or issues that the country needs to deal with. Look at what is happening for what it is—people who are tired of being abused in every way imaginable by whiteness, white people and white supremacist ideology and institutions in this society—boiling with rage. Resist the feelings of being persecuted for things you didn’t and wouldn’t do. Resist the urge to judge or condemn looters. Resist the impulse to impose your preferred modes of problem solving. Don’t turn to your typical experts for tips and talking points. Accept that you don’t understand and that you are not supposed to because you have not done the work yet. And you have not done the work because no one has ever challenged you to do it. Or if they have, you haven’t accepted the challenge. Either way, a deep, compassionate understanding of the black experience has never been presented to you as a requirement or prerequisite to anything that capitalism places any value on. You didn’t need it to get through high school or college or to get a good job or to rise the ranks of whatever industry you are in, or find a home in a good neighborhood, or fall in love. Engaging with blackness is an option for you, one you can always “opt out” of.

I, on the other hand, had to learn how to navigate your world and mine. I had to develop an ability to see the world both as it is and as you see it. In order to survive and build a life for myself, I had to learn how to think two, three steps ahead. I had to be adaptable, resourceful and resilient because I never got the same opportunities or had the same room to fail or mess up without it being a broader indictment of the race and confirmation of our basic ineptitude.

In the course of our lives I have come to know you (or at least whiteness) far better than you know me. So, at least, consider what I have to say to you—all of my white male friends of a certain age who I love so dearly. I need you—we need you—to step the fuck up.

Now, I have some sobering news. You are likely entering this conversation at a beginner’s stage even if you don’t think so. The good news is that’s okay. Just because you aren’t in charge of command or don’t feel certain and clear about your role doesn’t mean you should disengage. You wouldn’t hit the weight room for the first time and think you can squat 500 pounds. You would accept that you have to commit to going to working out every day and to struggling to build muscle over time. You would do it because you want the results. Because you want to look in the mirror and feel good about yourself.

I need you to want to fight racism with the same intensity you fight your love handles.

I need you to go as hard with learning about what’s going on and why it’s wrong and what you can do as you go with intermittent fasting, paleo dieting, lifting, sprinting, Pelotoning, Joe Rogan podcasting—whatever it is you do to get the satisfaction you seek.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

I need you to seek out black voices beyond those who show regularly up on MSNBC or CNN, in the New York Times or the Washington Post—including mine. The views of the black intelligentsia and even black entertainers and athletes are valid, but they are not the be-all, end-all.

But here, my friends, is what I want you to do first and foremost: begin to understand how racism has harmed you and your life and will harm the lives of your children if you don’t step up now.

In America, we talk exclusively about racism’s effects on people of color. Think about the ways systemic racism—the latest woke buzz phrase—is discussed.

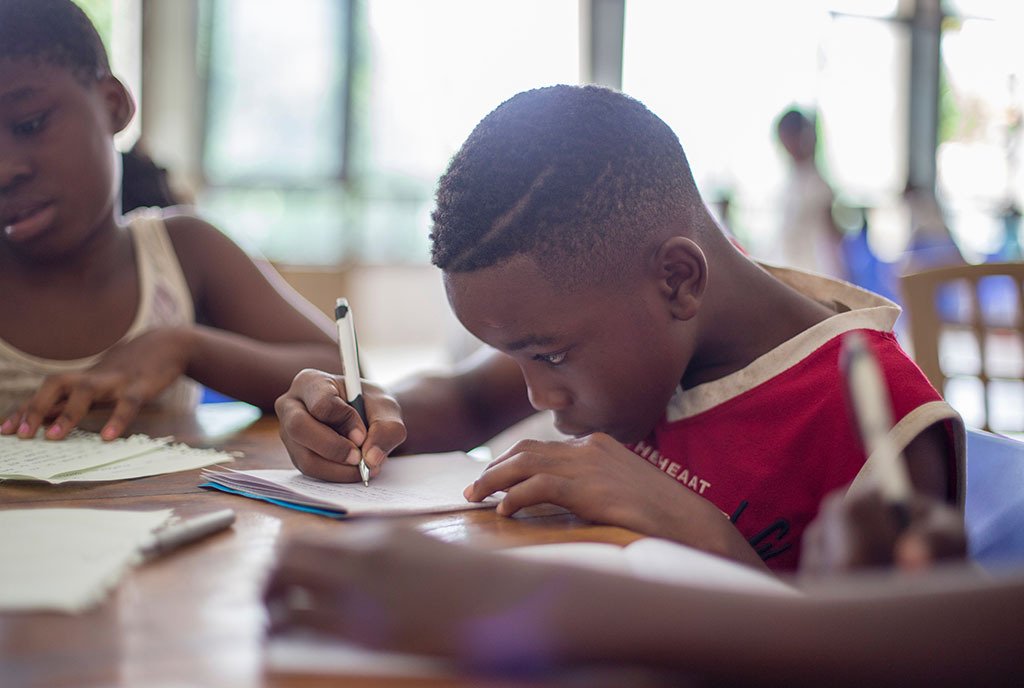

We talk about various outcome disparities in health, wealth, home ownership, education, criminal justice involvement, and mortality.

These are all measurable indicators and totally valid and necessary means by which to track racism’s effects. But by focusing only on what we can measure or have invested in measuring, we reinforce the ideas that exist in too many white minds who have little to no contact with people of color about the entirety of the black experience. The story that the data tells about black life is one of abject lack. And that “lack” frame informs the way so many white people encounter black people and black life. (To give but one example, that dominant narrative frames the charitable industrial complex that in turn shapes the current nonprofit landscape—organizations tell a story of “lack” to tap into white philanthropy’s guilt and abundance).

One on hand, the “lack” frame fails utterly to measure or account for resilience, generosity, kinship ties, empathy, compassion, community, and many other human qualities that exist in abundance in black communities.

On the other hand, it has allowed white people to develop, sustain, and pass down (explicitly and implicitly) a warped set of ideas about whiteness and wellness from one generation to the next.

Recently, the largest counties in Ohio and Wisconsin passed resolutions declaring racism a public health crisis. A Minneapolis councilwoman has suggested that her city passes one as well. This is an excellent start. The shortcoming and concern that I have is that these resolutions only define the problem as one afflicting black people. They situate white people as allies in the struggle, not among the afflicted. They don’t talk at all about the damage that deep-seated white supremacist ideas and unfounded fears of and threats posed by the presence of black people in what are thought to be white spaces (neighborhoods, parks, pools, apartment buildings, senior leadership roles) does to the white psyche. They don’t help white people understand that if they don’t do their own work, they might be the next Amy Cooper.

If nothing else I have said compels you to do your own work to understand how racism has affected you, then consider how Amy Cooper’s life has been upended in the past week. I’m willing to bet she didn’t consciously know that she was afflicted with racism. She found herself in a stressful situation and it just kicked in. Now racism has stripped her of the life she knew and labeled her a pariah.

Racism is a disease. It is a sickness. It is an affliction. It doesn’t live solely in systems of oppression that stunt black life. It lives in all of our brains. Studies have shown that our empathetic neural responses decrease significantly when we view faces of other races. Those and other brain responses translate to a host of behaviors including avoiding people of color, presuming anything black is inferior, devaluing the contributions black people have and continue to make to this world, diminishing our intellectual accomplishments and disbelieving our stories unless they can be verified through means you deem credible. It also lives in the bodies and behaviors of white folks who consider their own culture and background milquetoast or vanilla and fetishize and exoticize black culture and cultural expression.

I am convinced that until white men are able to appreciate that racism has robbed their lives of a fullness and richness that no amount of material success, positional power, or achievement can match or make up for, we are all trapped in the ebb and flow cycle of white violence and pain that has now marked my entire life; until you are able to extend empathy and compassion beyond your immediate circles and experience our pain and suffering as your own, we cannot see the lasting change we all seek.

Please don’t mistake what I am suggesting. You are not our savior. We do not need you to think for an instant that it is your job to fix the problems of society. We do not need you to start another nonprofit to save us or to join another board to help us. What I am suggesting is that you join us in the struggle and that you start by looking at your own life and figuring out your blocks in emotional connectivity and gaps in learning and understanding. Talk to other white men. Talk to your children. Reach out to your POC friends like me and ask how we are doing, then tell us how you are doing and what you are doing, then be prepared to learn but also to contribute to the conversation. Don’t think that you are doing the work because you are listening, taking it all in. Put yourself on the line. Be willing to risk discovering uncomfortable truths about yourself. Give up the need to be the white man with the answers or the discomfort of being the white man who isn’t expert on race. Those are false notions embedded in white supremacy ideology that have likely brought you stress and misery. Accept that you will make mistakes and have the grace to ask for forgiveness. Just be human and go in.

To get started on your journey, here is a solid reflection tool created by white people for white people. Here is an excellent tool to root out white supremacy at work. Here in an oldie but goody on white privilege. Finally, here a checklist that is a little dated but still quite useful.

The problem we face now is that Americans have been trained to see racism as black people’s problem. In recent years, business has come to realize it is harmful to the bottom line and responded with diversity initiatives. Those have had uneven success in part because you have outright resisted them or relegated them in your mind to being for minorities, LGBTQ folks, and women. They are and have always been for you too.

As a friend who cares about you, appreciates you calling to check in on me and needs you to be part of the solution, I implore you to keep going. You are only beginning to recognize that racism is toxic to your life. You still have far to go in understanding the warped notions that lie within. Stare into the abyss, the hole, the missing parts of your humanity that keep you from being able to connect deeply with people of color beyond the comforts of the workplace where invariably you hold positions of power and authority or through the lens of sports and entertainment. Consider where else in your life people of color show up? How do they show up? How do you show up? Look back on your life experience to find out what happened to you regarding race, how it affected you, and use that information to change your life, because we need you fully in this fight.

With Deep Love,

Dax

This article was originally published in the author’s blog and is reprinted with the author’s permission. A book titled Letters to My White Male Friends is forthcoming from St. Martin’s Press.