Across the country, a variety of efforts to rally in response to the current COVID-19 pandemic emerged in the philanthropic sector. From the time we entered crisis response mode until this moment today, one word continues to surface in Zoom calls and webinars across the sector: “Urgency.”

It doesn’t matter if your response role was to rally donors to give toward a crisis response fund, to give the grants, to do a needs assessment of grantees in your portfolio, or to gather the most up-to-date information about programs, policies, and practice changes impacting the nonprofit sector. Whatever role you are playing right now in philanthropy, at the heart of any motivation to make adaptations, innovations, and create flexibility and new strategies in the last two or three months is that one word, urgency.

Although it has been a breath of fresh air to watch institutions mobilize quickly and do the right thing, this question about why we are moving so fast right now continued to rise to the top of my mind. Why is this moment so urgent? Underneath the answer to these questions is a much larger, deeper discussion that needs to surface in philanthropy.

As a racial justice advocate and woman of color in philanthropy, it is clearer now than ever that our careful, self-paced, and guarded approach to place-based grantmaking, the core function of a foundation’s existence in “normal” times, reveals that we never fully understood a critical truth of what racial equity work really means.

These are core realities that community organizers know and are driven by. What if, as a sector, we took this moment of crisis to align our definition of crisis and urgency with those on the ground, all the time?

These guiding truths are that:

- Communities of color have always been in crisis.

- Racism is THE pre-existing condition that creates the disparities we are seeing.

- Racism is an ongoing crisis that requires urgent, on the ground, innovative strategies to reduce harm.

- People tend to hold a belief about what qualifies as an “urgent” response, and it is almost always rooted in white norms about what a crisis actually is and when a nation experiences it.

History teaches us that when white people are implicated negatively in a social issue, urgency appears. What if COVID-19 did discriminate and only impacted Black and brown folks? Would the crisis response be similar in pace to the failed Hurricane Katrina response and relief efforts? Maybe the Flint water crisis? Maybe we can even compare it to policy responses to mass incarceration, or to Hurricane Maria relief efforts in Puerto Rico. We know it would not be the same, especially when we recall policy response efforts to the opioid crisis, which predominantly impacted white people.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

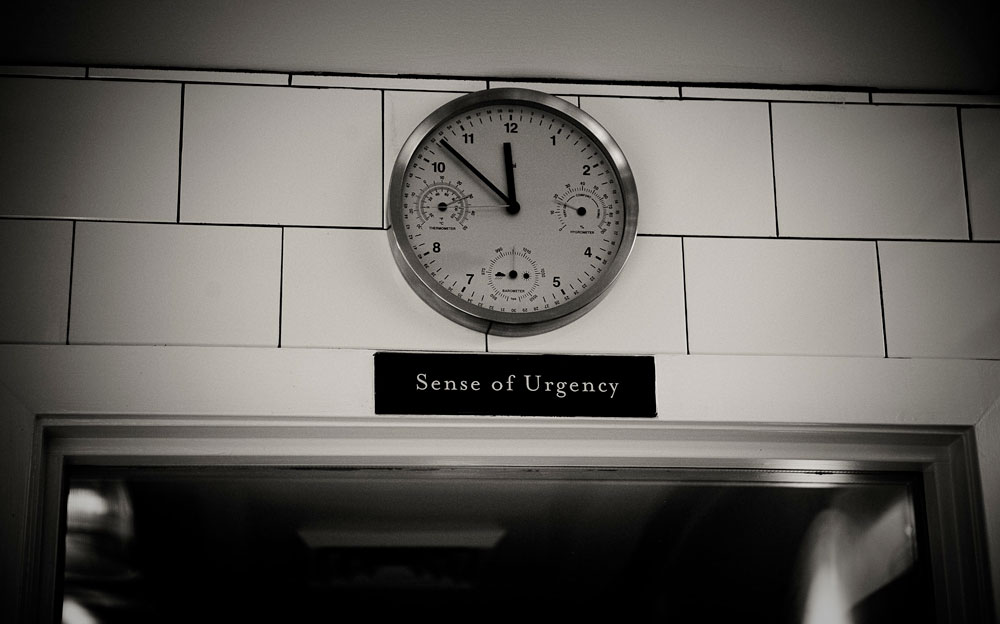

Until philanthropy reconciles with this fact, as a sector, we are on trajectory to continue to reinforce this crisis response philosophy. We have to decide to redefine “urgency” and “crisis.” We should never go back to our normal pace of racial equity work. When COVID-19 is over, philanthropy should never return to a world where there isn’t enough “urgency.”

COVID-19 has peeled away the layers. Now we must decide. Are the systemic issues that Black and brown communities disproportionately face daily urgent enough to call us into immediate action all the time? Do these issues demand us to mobilize resources, deconstruct philanthropic silos, undo reporting and application mechanisms, increase the spendable, and fundraise urgently? Will we see a shift to supporting mutual aid efforts, more grassroots organizations, advocacy, and public policy work? Or will we still hire consultants to tell us what we already know about the changes we need to make in our work and how to be innovative toward a racial equity objective?

Will we choose to move in the way that COVID-19 calls on us to move?

We also need to be real; Money is not the solution to these issues, and it is certainly not the solution to ending the racism that plagues our society and world, but it is a heartbreaking part of it in a capitalistic society of which we are a complicit part.

As long as philanthropic organizations exist, we have to look around and see that we are in crisis, always act on this sense of crisis, and recognize that after this pandemic is over, many of our communities will continue to be in crisis. This kind of a shift has the power and the potential to really change how philanthropy operates—now and in the future.

…

To the philanthropic institutions who were birthed from white dominant culture norms and charity mindsets and have shifted the value to racial equity but maintained the moderate pace: I write this with love but in unfiltered realness of our collective work, shared humanity and in protest of our past legacy and celebration of a new normal for which we have yet to define.