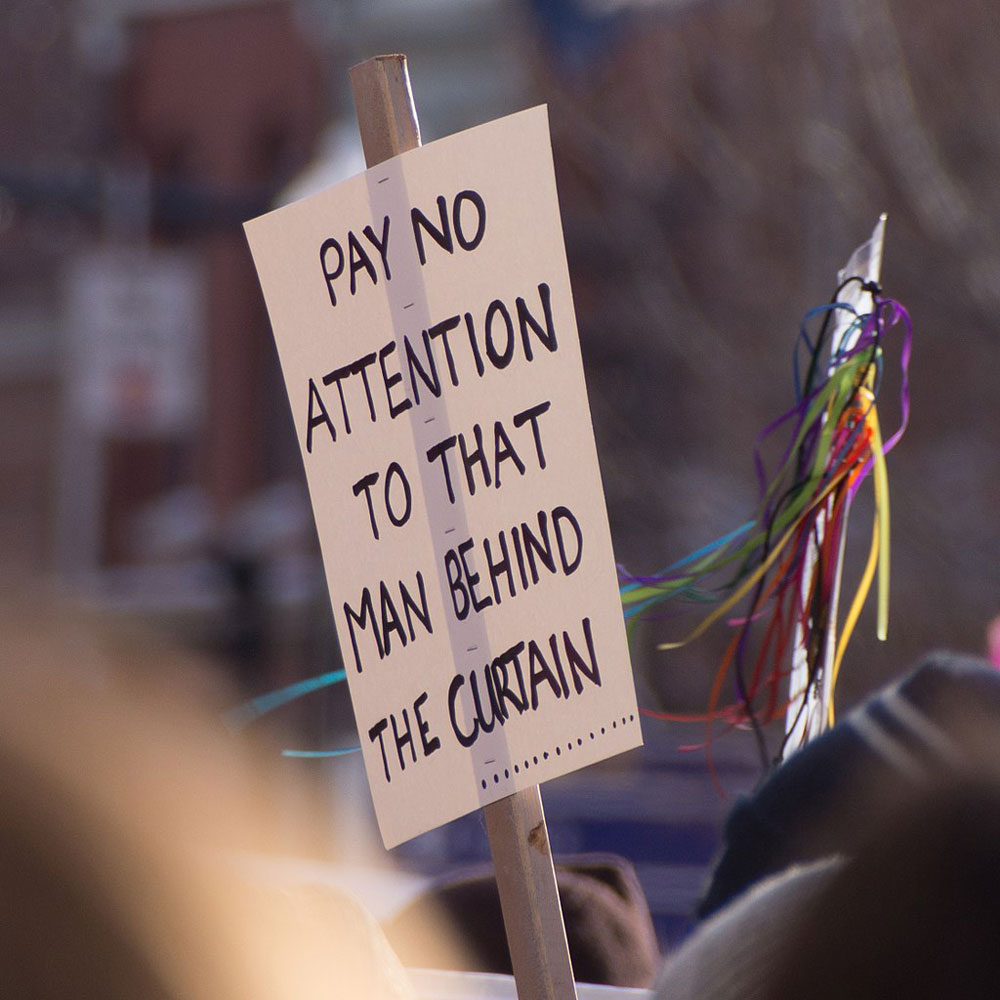

In the classic 1930s film, The Wizard of Oz, there is a famous scene where, after a perilous journey following a yellow brick road, Dorothy and her pet dog Toto—joined along the way by the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, and the Cowardly Lion—make it to the castle of the “great and powerful” Wizard of Oz. The “wizard” seeks to scare the group away, only to have Toto pull back a curtain that was hiding a film projector, revealing a rather ordinary man.

There is a message in this classic scene, and it extends well beyond the technicolor world of Oz. The movie, of course, was a product of its times—two times, really. The original children’s book by Frank Baum drew on images from the populist movement of the 1890s, scarred by economic depression. The classic film directed by Victor Fleming was released in 1939, during the Great Depression.

In 1939, US unemployment had fallen from its depression high of 24.9 percent but was still 17.2 percent. A decade-long drought also had ravaged much of the Great Plains, including Dorothy’s home in Kansas. Think back to those early, dreary black-and-white scenes in the film, made only more dramatic by the contrasting technicolor scenes in Oz. This was a very scary time, particularly in Kansas. Many “wizards”—too many to count—had failed Americans.

Today, we face what certainly looks to be our own economic depression, with food lines extending a mile long or even longer. Making the situation even more appalling is the fact that wealth at the top of the pyramid has once again consolidated and grown, even as conditions get increasingly desperate for so many. Between March 18 and May 19, the net worth of the nation’s 400 wealthiest families increased $434 billion, while tens of millions lost their jobs. Could the situation be any starker?

The answer to that question is yes, as a video recording of the murder of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis last month spurred a national uprising against the pernicious racism that enabled it. And then there is the COVID-19 pandemic itself, which has cost over 115,000 Americans their lives, with Blacks and poorer Americans being disproportionately numbered among the dead.

Meanwhile, the damage continues to mount. At least 100,000 small businesses have failed already, and many nonprofits are teetering too. A survey released last week by the Center for Effective Philanthropy found that an estimated 90 percent of nonprofits had to cancel or postpone fundraising events and 81 percent had to curtail operations, even as service demands increased for more than half. We could use some wizardly magic—and, often, in the world of nonprofits, that wizard is named “philanthropy.”

Philanthropic Responses to the Crisis in 2020

When public officials started to shut down the economy in March, it did not take long to realize this would result in an extraordinary crisis that would require an extraordinary response. Back on March 16th, philanthropic critic Vu Le wrote a blog post titled “Funders, this is the rainy day you have been saving up for” and called for philanthropy to double its payout rates. Two days later, NPQ amplified this call.

While philanthropy certainly merits criticism, it is worth acknowledging that, although not universally the case, many in philanthropy have been unusually responsive. Before the end of March, the North Carolina-based Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation announced it would double its payout, even at the expense of reducing the size of its endowment, deciding that “the loss of capital pales in comparison to the scale of need to cope with the worsening socioeconomic distress across the South.” The Libra Foundation soon followed. And nine philanthropic support groups issued a public letter in early April pushing foundations to give out more grant dollars during the emergency.

This past Thursday brought the biggest step yet, with five large foundations—Ford, Kellogg, MacArthur, Mellon, and Doris Duke–collectively agreeing to increase payouts by $1.725 billion—$1 billion from Ford and $725 million from the four others. In Ford’s case, the $1 billion will nearly double its payout for the next two years, given that it adds $500 million a year to the $520 million in grants it disbursed in 2019.

The details differ by foundation. MacArthur and Doris Duke have said they will use bonds, like Ford; Kellogg and Mellon are still evaluating their options. Doris Duke, like Ford, is committing to basically doubling its payout; others are not. Kellogg, for instance, has pledged a 50-percent increase in grantmaking over the next two years. Mellon says that with the borrowing its payout rate will increase to eight percent, which is similar to Kellogg. MacArthur’s $125 million is clearly less than a doubling of its grants, but its president John Palfrey tells the Times that the foundation will start with a $125 million bond offering and then assess whether more is needed, so the $125 million could prove just the first of multiple tranches.

To summarize, the added spending commitments are as follows:

| Added 2-Year Grant Commitment | Estimated Endowment | |

| Ford | $1 billion | $13.7 billion |

| Kellogg | $300 million | $7.3 billion |

| Mellon | $200 million | $6.1 billion |

| MacArthur | $125 million (first tranche) | $7 billion |

| Doris Duke | $100 million | $1.9 billion |

Many others in philanthropy have been less responsive. Notably, Larry Kramer at the Hewlett Foundation wrote on March 31st that his foundation would not increase its grantmaking due to a desire to maintain the “long-term condition of our endowment, whose spending power will diminish in real terms if payout in grants exceeds what’s necessary to sustain growth over time.” Now—perhaps due to rising stock market values, perhaps due to pressure from the field—the New York Times reports that Hewlett may be reconsidering its decision. But Hewlett is hardly alone; the Times article, for instance, also names Rockefeller Brothers and Carnegie as two other foundations that have yet to make a payout-increase commitment.

Still, the actions taken by Ford and others may have a broader impact. For one, it shows that it is in fact possible to raise payouts without selling endowment assets. But the decision to sell bonds to enable philanthropy to have its endowment cake and eat it too raises key questions.

What Is a Philanthropy?

As The Nation noted a few years ago, there is a common joke in the university world that Harvard is a “hedge fund with a university attached.” A similar joke, uttered perhaps even more quietly in the nonprofit world, is that foundations are hedge funds with grantmaking programs attached.

In both cases, there is more than an element of truth in the jokes. Harvard really does invest a third of its $39 billion endowment in hedge funds. And, if you look at the Ford Foundation’s 2018 audited financial statements, well over half of its $13 billion in assets were placed in “alternative investments,” including “hedge funds, global equity, credit, real assets, natural resources, and other investments through private partnerships, and holding companies.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

When Ford decided to double its payout, it could have sold off some of those assets in order to fund the higher payout. Doing some complicated math, if you sell off $1 billion of $13 billion-plus in assets, that would have left Ford with over $12 billion in assets.

Instead, Ford chose to issue bonds and maintain its present asset positions.

What are we to think of bonds as a financing mechanism? On a technical level, it is clever, and it allows Ford and the other foundations to issue more grants at lower cost.

After all, since the going interest rate for corporate 30-year bonds as of April 2020 is 3.24 percent, borrowing through bonds is a good deal. By contrast, stocks have an average return over the past 50 years of eight percent. And “alternative investments” typically outperform stocks, which is why Ford and Harvard invest in them. So, from a pure financial return standpoint—issuing bonds makes a lot of sense.

Other foundations too may realize they can do the same thing to double their payouts. For example, Kramer objected to increasing payout because he wrote it would require Hewlett to engage in “selling devalued assets from an already diminished endowment.” Well, guess what? Ford just committed to doubling its payout, and it will not be selling a single devalued asset from its endowment to do so.

Now NPQ has no access to the board room of the Ford Foundation. But one could easily imagine a boardroom conversation where one board member raised Kramer’s very objection, and then someone else around the—given COVID-19, I suppose “virtual”—board table said, “Wait a minute! Why can’t we float bonds just like my corporation does?”

In short, the tactical brilliance of what Ford and the other foundations are doing is really not in doubt.

On a philosophical level, however, the move perhaps ought to concern us. It raises questions because what it says is that foundations are committed to maximizing their investment portfolios—and will even borrow to do so. In other words, foundations through their investments help prop up a capitalist economy that often harms their grantees. By borrowing to make grants now, the foundations are in fact increasing their dependency on achieving the financial returns that make it possible to pay back their loans. Put differently, they are acting more like hedge fund managers than how they might like to imagine themselves.

It’s worth noting that foundations are not unaware of this conundrum. Back in 2014, Darren Walker, the president of the Ford Foundation, acknowledged that foundations are products of the capitalist economic system and asked, “How do we support efforts to change a system in which our own grantmaking resources are cultivated?”

There is, of course, a lot more philanthropy could do—starting with aligning the entire corpus of foundation investment with their mission. For its part, in 2018, Ford did commit to investing $1 billion by 2028 in projects that have social and environmental returns. That still leaves $12 billion-plus with no such commitments.

More broadly, the push for more, while surely needed amid our present emergency, forces us to ask hard questions regarding how we as a society produce that “more.” Few of us can claim complete independence or purity. We are all implicated in the present system—and stumbling as best we can, we hope, toward something better.

And, indeed, we also know that spending more is both necessary and insufficient. The numbers tell us this. Not long ago, NPQ published an article calling for an emergency charitable stimulus that would double payout requirements for private foundations for three years and could generate $200 billion in additional grant dollars during that time. That would be a great achievement—and yet it would be only a fraction of the government money thrown at the economic shutdown in the past few months.

The “great and powerful” philanthropic edifice looks a good deal less great and powerful when the philanthropic funding curtain is opened—even a little bit.

Truth be told—there are no wizards. This is just one more reason why how philanthropy deploys its grants matters at least as much as how many grants are made.

Not long ago, in NPQ, Ed Whitfield and his colleagues at the sunsetting Fund for Democratic Communities (F4DC) advocated for grants that build up community partners through fostering mutual aid. As Whitfield and his colleague wrote last month, the long-term goal of social justice philanthropy should be to put “resources out into the world where they can continue to be of value to, and in the control of, the creators of the social value that we all depend upon.” In other words, F4DC sought to create community-controlled economic institutions that might persist, independent of philanthropy, for the long haul. As we look for a way out of relying on highly inequitable capital markets to promote inclusive ends, it is a path worth keeping in mind.