June 15, 2020; Guardian, Washington Post, and New York Times, “Opinion”

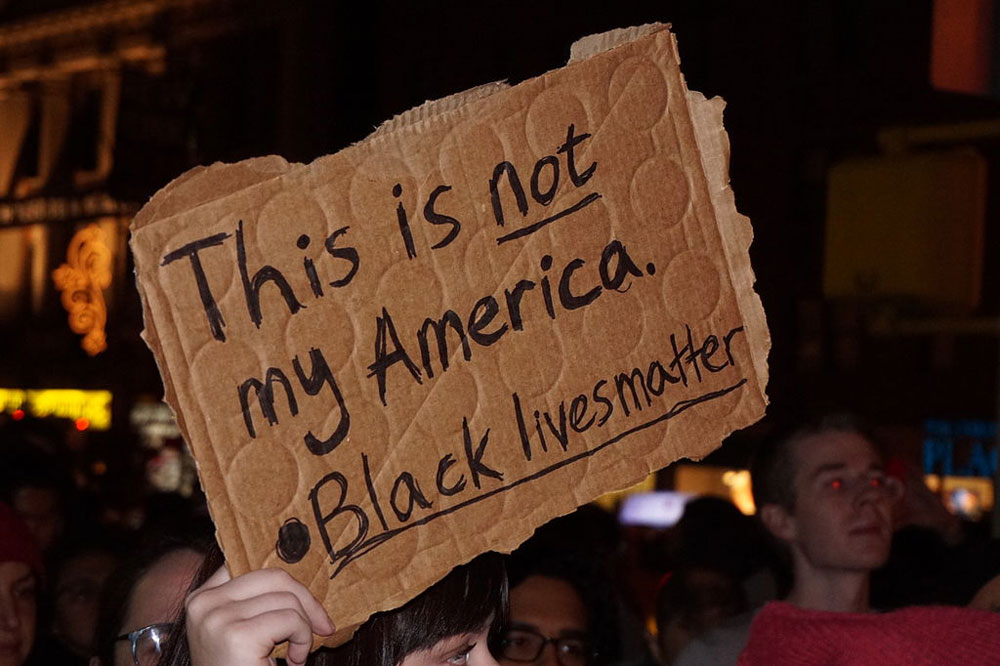

Three weeks of daily marches and car caravans taking place in hundreds of cities and towns have kept our nation, famous for its short attention span, from moving on to another issue. Sparked by the murder of George Floyd and fed by the glaringly disparate impact of the pandemic as well as ongoing police brutality, demands to finally take responsibility for our nation’s embedded discrimination have grown louder. Individually and collectively, we are called to address the systemic ways our society has punished communities of color and those without wealth.

Even many who do have power and money have joined in the outcry. Writing in the Guardian, former US Secretary of Labor Robert Reich notes that the demand for a reckoning with the impact of racial inequality has reached executive suites and boardrooms.

Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JPMorgan Chase, took the knee last week before cameras at a branch of his bank. Larry Fink, CEO of giant investment fund BlackRock, decried racial bias. Starbucks vowed to “stand in solidarity with our black partners, customers and communities.” The Goldman Sachs chairman and CEO, David Solomon, said he grieved “for the lives of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and countless other victims of racism.”

But are these more than gestures? With racism and wealth inequality so deeply intertwined, will there now be support for the difficult work of addressing systemic poverty? Or is this just another way to manage a crisis and protect corporate interests?

Beyond platitudes, corporations have focused on increasing donations to organizations working on the forefront of racial and economic change with more than $500 million pledged as of the beginning of this week. They have again pledged to diversify their workforces and their boardrooms, which are poorly representative of our country.

These promises aren’t new. Corporate philanthropy has often been used to signal tepid support without having to make the internal cultural shifts required to achieve real change. Pledges of a more diverse workforce have been heard before, yet corporations remain largely white spaces and the wealth gap continues to grow.

As Jamillah Bowman Williams, an associate professor at Georgetown Law, said to the New York Times, “Giving money away is definitely much easier than addressing these issues internally. It’s corporate P.R., because it transfers the responsibility of solving the problem to outside organizations. If they are generally opposed to racism, they should hold up the mirror to themselves.”

Real change means changing how the economy is structured and business is done. For example, a recent study of single-family home loans in Chicago by WBEZ showed a shocking—yet, sadly, not surprising—pattern or racial bias from banks and other mortgage lenders. They looked at more than $54 billion in loans and found “68.1 percent of dollars loaned for housing purchases went to majority-white neighborhoods, while just 8.1 percent went to majority-black neighborhoods and 8.7 percent went to majority-[Latinx] neighborhoods.”

One of those cited by Reich for empty words, Jamie Dimon, is the CEO of JPMorgan Chase. The research found that his bank’s Chicago lending program was even more discriminatory than the average lender; eighty percent of the $7.5 billion in loans it made went to white neighborhoods.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Beyond the difficulty these functional redlining practices place on individual homebuyers wishing to settle in neighborhoods that lenders have turned their back upon, there’s a diminishing of the overall quality of life. Brett Theodos, a senior fellow with the Urban Institute, notes that, based on his research, “lending for home purchases determines whether you have a pharmacy to shop at or a dry cleaner to go to. It determines what rehabilitation work is going to happen to the multifamily stock that’s in your neighborhood. It determines what other single-family stock is going to be coming to your neighborhood.”

Maurice BP-Weeks, co-executive director of the Action Center on Race and the Economy, says in the Washington Post, “These are some of the same banks that ripped so much wealth from black and [Latinx] communities during the foreclosure crisis.”

BP-Weeks calls for more than superficial changes. “Without meaningful actions such as directing profits back into black communities, eliminating racial pay disparities, increasing hiring from black neighborhoods and promoting black employees,” he says, “corporate statements supporting Black Lives Matter stand empty.”

“All of these things would show that this is more than just platitudes.”

Reich doubts that words will be matched by significant action. To do so would mean the sacrifice of personal wealth, political power, and social status. From his vantage, their strategy is one that fuels the racial divide to prevent coalitions from forming.

The rich know that as long as racial animosity exists, white and black Americans are less likely to look upward and see where the wealth and power really has gone. They’re less likely to notice that the market is rigged against them all. They’ll cling to the meritocratic myth that they’re paid what they’re “worth” in the market and that the obstacles they face are of their own making rather than an unjust system. Racism reduces the odds they will join together to threaten that system.

[…]

The only way systemic injustices can be remedied is if power is redistributed. Power will be redistributed only if the vast majority—white, black and brown—join together to secure it.

Those demanding real, deep change will need to keep the pressure on. Settling for limited progress may doom us to look back at 2020 as another failed opportunity to fulfill nationally stated values pledging fairness and equal opportunity to all.—Martin Levine