January 21, 2014; Chicago Tribune

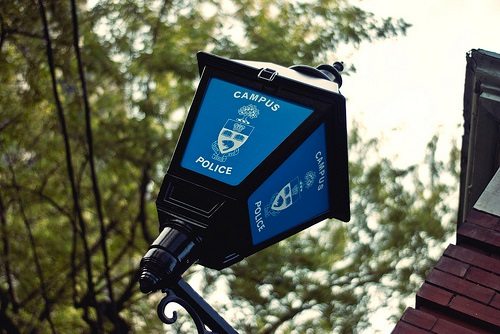

Most large schools of higher education employ their own school security personnel, who often take the place of local police officers on campuses and have similar responsibilities. State colleges and universities are state entities, and private colleges and universities receive government funds. States have public records laws, much like the U.S. Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), requiring government bodies to provide records to citizens and press. However, courts and administrative bodies have not resolved whether colleges and universities and their contractual agents—like the campus police—are covered by public record laws, leading to situations where some students are protected at the expense of others and the public at large.

On January 15th, ESPN filed a lawsuit against the University of Notre Dame alleging the school is violating Indiana’s public record laws by withholding police incident reports linked to student-athletes involved in potential campus crimes. The university claims their security personnel are not required to provide these records because they are employed by the university rather than a government agency. Indiana administrative rulings and court decisions have not consistently ruled on whether university and college security police are covered by these laws.

During this same period, ESPN requested similar records from the Tallahassee Police Department. On December 24th, the Tallahassee Police Department released hundreds of records involving Florida State University athletes. The request was related to a story in the New York Times documenting an automobile hit-and-run incident taking place in the early hours of October 5, 2014, the day after a FSU football game victory. The driver of one of the cars was FSU quarterback Jameis Winston, who hit another car driven by a teenager on his way home from work. Both cars were totaled. Instead of waiting at the accident scene, Winston and his two passengers, also athletes, left the car and fled.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The incident happened off-campus, and the Tallahassee police reached out to university police and its athletic department. The outcome: Although the athletes fled the scene, Winston was driving on a suspended license, and there was evidence of alcohol consumption by the athletes, police dismissed the episode as “too minor” to file a report or enter the accident on the police online database.

Reporters request university and college records for reasons beyond activities of students. In the fall of 2014, a University of Delaware student newspaper reporter attempted to get information on the university’s plan to partner with a private company to build a large power plant. Delaware public information laws exempt public universities, therefore the reporter was unable to get any information on the university’s activities. The outcome: University activities remain unchecked and the student reporter was unable to learn how to utilize state public record requests, although she did learn their limitations.

Pennsylvania public information laws have similar exemptions as Delaware’s. Last June, the Pennsylvania senate unanimously passed legislation to limit these exemptions. Not surprisingly, these efforts were met by heavy lobbying activities by the state’s universities and colleges.

One state with broad public information laws is Michigan. Michigan’s Freedom of Information Act explicitly covers public colleges and universities. Exemptions in the law are very specific, protecting individual students’ loan records, general testing documents, and even some materials related to applications of those interested in becoming a school’s president.

Many universities and colleges are the size of towns or small cities. Rarely does a bright line separate a campus from the town it’s connected to, and there’s even less of a line defining school police jurisdiction. Without public record law requirements, university and college activities are easily hidden, creating potential conflict of interest and less security for all.—Gayle Nelson