This article comes from the summer 2019 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly. It was first published online on July 22, 2019.

It goes without saying that nonprofits take many different shapes and forms, but all have a variety of stakeholders—that is, individuals and entities with a stake in their work, either because it can benefit them or because it can harm them.

Nonprofits are not like businesses, which have long believed that they are always responsible first to shareholders and only secondarily responsible to others who might be affected—even profoundly—by their actions. In the case of businesses, there is a bright line of accountability drawn from the organization to the provider of capital: the shareholder. Other accountabilities, even to such things as the environment, have tended to fade as prioritized requirements unless specifically elected as core and necessary to the organization’s identity or brand.

Nonprofits formally have no shareholders—that is, no one is supposed to be personally enriched by the organization’s work. But the teeth in nonprofit accountability relationships—both in actual and legal terms—are often more commonly and carefully attended to when the organization is receiving money dependent on its compliance than they are when stakeholders have a more general moral call on its attention. This has the effect of further disenfranchising the very populations meant to be served, and it should be unacceptable as common practice in civil society.

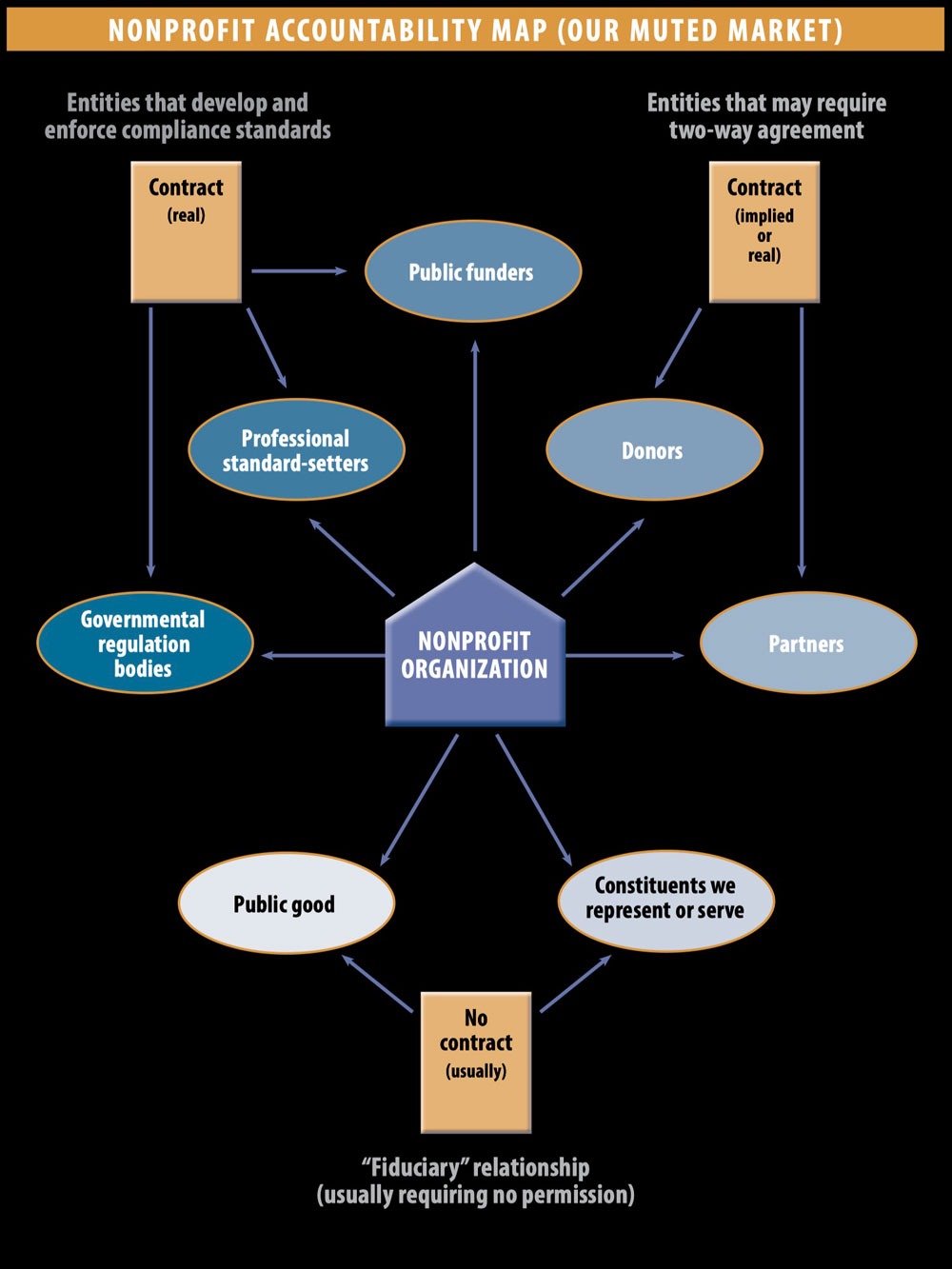

This makes nonprofit stakeholder accountability look—with some variations—something like the map below.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

On this map you can see, at the top left, the entities that develop and enforce compliance to standards that they either set independently or have a significant influence in setting: governmental regulation bodies and professional standard-setters, which/who can force accountability to standards they have established, and public funders, which/who not only have regulations with which nonprofits must comply but also, importantly, a contract, which can be very granular, and violations of which can shut down an organization in fairly short order. (Not all organizations have this kind of money, of course.) These categories are depicted as darkest in color (on a spectrum), because they receive the highest level of nonprofit accountability.

At the top right of the map can be seen entities that may require two-way agreement. These are paler in color, as accountability is weaker for these categories. In the case of donors (including large and institutional ones), there may or may not be legally enforceable contracts. In some cases, the contracts are written documents binding the grantor and the grantee, but in other cases, the contracts with donors may be implied by the organization’s own fundraising materials. In these latter cases, the organization is likely to be held accountable by a government regulator (see the left side of the map), and generally only well after the fact. In the case of partners, these relationships can vary widely—from very formal and backed by a contractual agreement to informal and voluntary. The result of not being accountable in one of these relationships, therefore, can range from having legal blowback to having no consequences whatsoever. In the middle of those two examples is the reputational consequence of being seen as a bad partner, and that may risk the future prospects of your organization’s being able to affect the larger operating environment.

This brings us to the lower middle of the map. Here nonprofits have perhaps the highest level of “fiduciary” relationship but ironically very often no mechanisms for accountability (hence the pale shade) to constituents we represent or serve (except those mechanisms that can be derived from organizing or whistle-blowing, or by the organization electing to make a contract of sorts to hold itself accountable). Nonprofits also have no firm accountability to the public good except what the sector elects or what can be wrested from it.

Functioning Ethically in a Muted Market

Such accountability mechanisms are based in relationships that contain conversations about what the organization is trying to accomplish and how that can best be achieved in the current environment. Maintaining a fiduciary relationship in which there is money given in stewardship for the benefit of an entity with which you do not consult when consultation is available, is unsupportable as an issue of trust. It is the ultimate in neoliberal practice, it is antidemocratic, and it is the way too much of this muted market now functions.

Are You Functioning Ethically? Questions to Ask:

- Who do you say the organization is accountable to? With whom do you spend the most time, both in setting the design of the program and in talking through necessary adjustments?

- Who (or what) would the people your organization serves say your organization is accountable to? Who do they think are the real stakeholders?

- Who is involved in defining and evaluating “success”?

- Who are those who have the deepest stake in your organization’s “success”?

- How do goals get set (and by whom), and how does the organization evaluate/measure progress?

- Who can be most harmed by what you do and how you do it—and even how you talk about it/ them? Who is having things done in their name, purportedly for their benefit, but without their counsel?

- Who in the organization is currently most influential over resources?

- Who in the organization is most influential in setting the organization’s agenda?

- To what extent or in what ways are the organization’s own employees stakeholders?

- Who is not a recognized stakeholder who should be? (This requires a deep questioning of the relative strength of various organizational relationships. For instance, is there a demographic group that should rightly be consulted, served, and represented, but which is now excluded from some or all of those functions?)