June 22, 2020; MEAWW (Media Entertainment Arts WorldWide)

A foiled effort to topple the statue of Andrew Jackson in Washington, DC’s Lafayette Square, next to the White House, on June 22nd strikingly symbolizes our current historical moment amid the social unrest unfolding since the police murder of George Floyd a little over a month ago.

This is the same Jackson, who back in 1804, 29 years before becoming president, posted a sign for an escaped slave that read, “Stop the Runaway…Fifty dollars reward…a Mulatto man slave…all reasonable expenses paid—and ten dollars extra, for every hundred lashes any person will give him, to the amount of three hundred.”

The Lafayette Square statue of Jackson is one of many symbols of white supremacy that are being questioned and even undone—from NASCAR banning the Confederate flag to the rebranding of Aunt Jemima. Yet racist systems are not going quietly. The protestors who sought to bring down the statue of Jackson were met with tear gas. The statue is still standing, now behind a newly erected eight-to-nine-foot fence.

But why are protestors targeting the statue, and what is the significance of this White House vehemently defending it, including the signing of an executive order to do so? At the center of this impasse is the legacy of well-documented abuse towards Native Americans and the enslaved enacted by the “President of the People.”

Jackson brought about the displacement and deaths of thousands of Native Americans through the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the most-often-cited human rights crime of his presidency and legacy that aided American expansionism for another century. The second, was the source of his family’s accumulated wealth through the slave trade.

The cruel indifference underpinning Jackson’s Indian Removal Act began long before 1830. After gaining notoriety during the War of 1812, Stephen Sabot notes in Jacobin, “Jackson waged a brutal campaign against British forces and the allied Creek tribes.”

At Fort Mims in 1813, his troops burned settlements, killing men, women, and children. At Tehopeka in 1814, he personally supervised the mutilation of eight hundred corpses. (We know the exact number because his men cut off their enemies’ noses to count the dead and preserve a record of their victory, turning long strips of flesh into bridle reins).

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

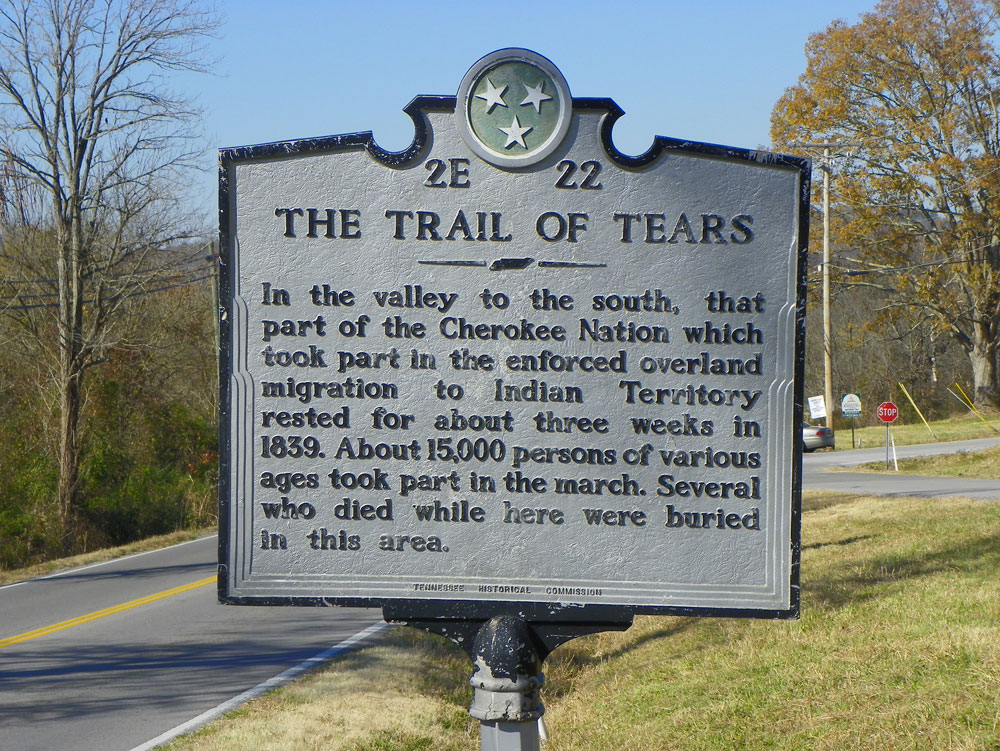

Despite Jackson’s assertion that his Indian Removal Act was benevolent, few Cherokee left their lands willingly, with 15,000 forcibly being removed under President Martin Van Buren in 1838 in what became known as the Trail of Tears. About 4,000 of the 15,000 Cherokee died while making the forced journey to Oklahoma.

Jackson’s targeting, swindling, and removing indigenous peoples from their land is inextricable from his view of and engagement in slavery. When he bought the Hermitage plantation in 1804, the same date as his runaway slave advertisement cited above, he owned nine slaves; 41 years later that number had grown to 150.

As Dylan Matthews wrote in Vox in 2016, “Indian removal was not just a crime against humanity, it was a crime against humanity intended to abet another crime against humanity: By clearing the Cherokee from the American South, Jackson hoped to open up more land for cultivation by slave plantations.”

The protestors’ targeting of Jackson not only raises the question, “How bad was Andrew Jackson?” but also “Why does he remain a protected historical figure?”

The image of Jackson is lauded by President Donald Trump as a reflection of himself, a populist rising from obscurity to wealth and power, though Jackson as president actively pursued genocide of Native Americans, and made his fortune through slavery. Still, he continues to adorn US currency and the lawn adjacent to the White House.

In the last month, we have seen a widespread call to dismantle the historical symbols of US social and economic systems built on racism and the suppression of Black and brown peoples. But for systems of power, it is not simply about the removal of a statue, but about the deconstruction of the very tenets of that power and the very core of white identity and the very real existential fear that deconstruction induces.

At this crucial moment, amid widespread social unrest and a global pandemic, it is imperative that we no longer continue to disavow the nation’s past and the images associated with that past, but finally shed light on what has for too long remained in the shadows.—Beth Couch