“BLACK AND WHITE MOON SCREEN” by Cassandra Courtney / www.ccourtneydesigns.co.uk

Let’s play a quick game! This game will teach you how to better formulate and execute strategies for your nonprofit organization. Ready? Good.

You are the executive director of a domestic violence shelter in Anytown, U.S.A. You are faced with the difficult decision of whether or not to apply for a grant from We Will Fund You Foundation. In order to make your decision, you consider the following:

- It will cost you $5,000 to apply for the grant;

- The grant is for $20,000;

- There is one other competitor for the grant, Another Shelter Charity; and

- The foundation will award the grant to you, the other organization, or both equally.

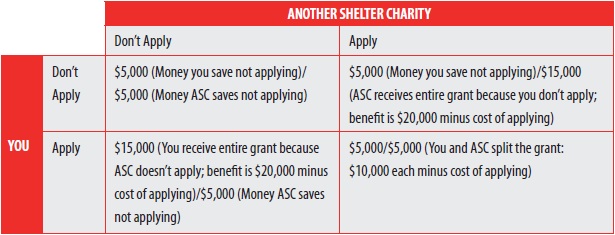

In preparation for your decision, you may develop a matrix (if you are so inclined) like the following:

The strategy this matrix describes is a classic example of game theory known as “the prisoner’s dilemma.” This particular example assumes that the foundation prefers to fund both organizations if both organizations submit proposals, and the decision you must make is to apply—and thus jeopardize the $5,000 fee for the possible return of $20,000—or not apply—and thus save the $5,000 fee (of course, while saving on the fee, you lose out on the chance of receiving the $20,000 grant).

Using your strategy matrix, did you decide to apply for the grant? If your response is yes, you selected what game theorists call “the dominant strategy.” The dominant strategy leaves you in a better situation no matter what the strategy is of Another Shelter Charity. If you apply, you stand to have a net benefit of $15,000 (if Another Shelter Charity does not apply) or a net benefit of $5,000 (if Another Shelter Charity does apply and the foundation decides to split the grant between the two organizations).

If you are struggling to understand how a simplified scenario like this relates to your more complicated reality, don’t worry. This only means you are not susceptible to mainstream economic decision making—which may explain your success as a nonprofit leader!

Time to Take a Stand

The ongoing invasion of for-profit management theory is more than a potential threat to nonprofit organization productivity. The far greater implication is a fundamental transformation of nonprofit culture through management frameworks emphasizing mainstream economics over social values. Game theory is one of the most recent invaders, and it exemplifies an alarming trend that nonprofit sector advocates have been reticent to push back against.

The more than one million United States charities confront our most vexing social problems. Managers awake each day with the arduous tasks of sustaining a business, providing services that never equal the level of need, and satisfying the competing demands of a diverse and fickle set of stakeholders. Whereas for-profit managers awake with the fear of not enough customers, nonprofit managers awake to the reality of too many.

It is for this reason that our quest for new nonprofit management frameworks is necessary. My question (and more often concern) is, Why are those of us engaged in the nonprofit sector so willing to jettison our management knowledge for models developed in the for-profit sector? In the ongoing search for a panacea promising to salvage nonprofit management from its “primitive state,” we (meaning academics, authors, educators, consultants, and managers) willingly adopt models from our for-profit relatives with little to no hesitation. For example, in the last two decades the terms crowding out, social enterprise, and venture philanthropy have entered the lexicon of nonprofit management with limited resistance. Why? As a nonprofit community, have we considered the negative impacts of commercial behavior and/or venture capitalism? Have we offered alternative perspectives on concepts like value and efficiency?

I believe there is worth not only in protecting our nonprofit culture but also in cultivating our sector-specific body of knowledge. A sector comprising 9.6 percent of U.S. wages and salaries and more than 5 percent of GDP has made verifiable contributions to our collective understanding that should be understood and augmented.1 Thus, the following offers a rebuke of game theory (and its insidious relatives that have made or will make their way into nonprofit management parlance) as a suitable nonprofit management model. More important, I offer preliminary criteria that we can use to judge the utility of new models. Such criteria will not restrict the flow of ideas between sectors, countries, or disciplines; instead, it will ensure we do not discard the abundance of nonprofit management knowledge in our humble quest for improvement.

Game Theory: A Primer

Game theory owes much of its mainstream acceptance to John Nash and his “beautiful mind.” Beginning in the field of mathematics, game theory (initially operationalized by the “Nash equilibrium”) was quickly adopted by economists as a decision-making model. Before I dismiss its relevance for nonprofit management, I would be remiss if I did not acknowledge the utility of game theory as a model in public policy and military strategy. It is partially because of this success that management scholars and consultants have been so eager to find applications for game theory in management fields.

Most people are introduced to game theory through “the prisoner’s dilemma.” Like our example, this game positions the player against one other player. The goal of the player is to determine the action that will maximize his or her benefit. At this point, you may interject: How am I supposed to know what the other player in the game will do? A good question, but one revealing your lack of initiation into economic axioms.

Like all mainstream economic decision models, game theory establishes a set of rules (axioms, or assumptions) that govern the actions of players. The rules can be summarized as follows:2

- The preferences of all players are revealed. In our example, this would mean that we know the foundation plans to split the grant if both our organization and Another Shelter Charity apply. It also means we know what Another Shelter Charity prefers.

- All players have perfect information. This is a classic economic axiom. For this to be true, as a nonprofit manager you would have to be aware of every possible action available to you. For example, let us assume you are planning a fundraising strategy. With perfect information, you would know every foundation that might possibly fund you, every donor interested in your mission, all government grants available to your programs, and the potential customers possibly willing to pay for your services. Additionally, you would need to know all possible competitors for foundation grants, donations, government grants, and fees for service. To further complicate matters, you must also repeat this same process of knowing for each and every fundraising scenario.

- You make decisions that maximize your organization’s benefit. This is the base of rationality underlying most economic decision models. However, what happens if maximizing utility is defined as stakeholder approval, and one stakeholder’s values diametrically conflict with another stakeholder’s values? This point has been well documented in the arts community, where organizational leaders find that the interests of artists (new productions) conflict with the interests of funders (traditional productions).3 By the nature of the two stakeholders’ interests, no strategy will maximize approval.

- All players are rational and intelligent; therefore, it is possible to predict the actions of all other players. In other words, if you know a funder is rational, you simply need to figure out what maximizes their utility and then establish a strategy enabling their funding of you to maximize their utility.

- The goal of the game is equilibrium among all players. Ahh, equilibrium—the state of perfect balance, where all consumption and production is maximized. Of course, not all actors seek a balanced solution. Nonprofit A may want more than its share of equilibrium distribution. In this context, equilibrium is a predetermined goal at the outset of the game. In reality, actors in a system cannot know how their decisions impact equilibrium, and thus seek less balanced outcomes.

Using matrices and mathematical calculations, game theory propels the manager through a series of moves or scenarios. Each move is built on assumptions about the behavior of other players in the game. The result is either a dominant solution or a mathematical probability of success for a strategy. But what if a situation cannot be reduced to probabilities because of uncertainty? I will deal with that problem and other limitations of economic decision models like game theory in the remainder of this article.

Game Theory’s Insidious Relatives

Hidden in the support for game theory is the belief that all human behavior can be reduced to probabilities and homogeneous behavioral motivations. The truth is, game theory is not alone in this approach. The good news is, the assumptions provide us with a rubric we can use to evaluate the validity of the theory.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Game theory demands adherence to its underlying assumptions. The assumptions create an environment in which decisions are made without uncertainty. If any one of the assumptions does not hold, uncertainty enters and the model loses predictive power. Deductive models suffer from this shortcoming.

For example, let’s revisit our opening game and see what happens when assumptions do not hold. Remember, we are operating under the following assumptions:

- The preferences of all players are revealed.

- All players have perfect information.

- You make decisions that maximize your organization’s benefit.

- All players are rational and intelligent; therefore, it is possible to predict the actions of all other players.

- The goal of the game is equilibrium between all players.

In our opening game, we assumed the foundation preferred to fund both organizations (if both organizations submitted proposals). This type of assumption obviously leaves out two potential options we did not account for in our matrix: a) the foundation only wishes to fund one organization, or b) the foundation does not wish to fund either organization. Nonprofit managers know that funders often choose between these very options, and, because your organization is not identical to the other organization, there is some likelihood the foundation could be more enamored with the other’s proposal. Another possible scenario occurs if the two key players and/or the foundation are operating on imperfect information. For instance, after submitting proposals, both you and Another Shelter Charity might discover that three other organizations are also competing for the same grant.

Often, in real world management, we operate from incomplete information. In this game, incomplete information changes the potential outcome of our decision. The dominant strategy we perceived with two players is no longer valid. Further, an inundation of proposals may alter the decision-making process of the foundation. Research has shown that when foundations have imperfect information on grantees, they rely on network information to make a decision.4 Stated plainly, they rely on their “friends” in the foundation world to provide them with information they use to serve as reasoning for their decision. Under this scenario, lack of perfect information has led to foundation decision making that is not rational. Thus, we can no longer predict the actions of the foundation.

The disruptions in the game have created a situation lacking an equilibrium solution. Game theorists would argue that a manager could set up a new game, with new entrants and a new range of foundation decisions, and run the calculation again. This is true. However, the new game is subject to additional disruptions. And even if we could possibly conceive of all the potential disruptions (which we cannot, because of imperfect information), when would a manager have the time to run all these games?

Total condemnation of a management theory for shortcomings in the assumptions of said theory may seem extreme. “Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater” is a common response from those in favor of models relying on rationality. For instance, Hagen Lindstät and Jürgen Müller argue that game theory provides managers with useful strategy options when faced with complex real-world scenarios.5 Despite theoretical limitations, they believe that game theory offers managers the best model for assessing trade-offs between risks and opportunities. Unfortunately, game theory’s rational underpinnings push decision makers down a path blocking important strategic options. This happens because we are forced to conceive of rivals who are intelligent, all knowing, and rational. In reality, decisions are made by human beings, and human beings make decisions based on experience and socialization. All human decisions are inherently not rational and are thus suboptimal from a game theory point of view.

We see this in the behavior of donors. “Crowding out,” a complementary theory to game theory, says government donations “crowd out” private donations because rational individuals will not contribute to an organization if someone else (in this case, the government) does so for them. Instead, they will save their donations for a public good that is not subsidized. However, empirical research shows that crowding out does not impact the behavior of donors.6 Why? Because donor behavior is more influenced by environmental factors, like the donor’s parents having modeled the behavior, than utility-maximization behavior. Because research shows that donors are not rational in their decision making, a model assuming their rationality is bound to exclude strategies that may prove effective.

Finally, in order for rational models to work, we have to have a homogeneous definition of value. In the for-profit sector, value is operationalized as price. If you buy a new iPad for $499, you and the retailer agree that the value of the iPad is $499. Nonprofit value is far more difficult to define. Using the example of domestic violence, we may find a multitude of factors influencing a shelter’s definition of value. The level of domestic violence in the community—whether or not someone has been impacted personally by domestic violence—and the perception of need for domestic violence services are just a couple of the criteria. If someone previously not impacted by domestic violence comes in contact with the damage incurred by an attack, personal valuation of services is likely to rise. This change, coupled with the imperfect information leading to a lower valuation before the change, explains the level of irrationality in nonprofit markets.

How to Decide

So the question naturally emerging from the above discussion is, How should we evaluate the usefulness of management models? Quite simply, we should utilize what we know. When confronted with a new decision-making model, we should first ask, How well does this model reflect the realities of the nonprofit sector? In order to avoid poor model fit, I suggest following these advisories:

You know what they say about assuming. When I was growing up, my mother would always tell me, “When you assume, it makes an ass out of u and me.” Sound familiar? The advice my mother offered so many years ago happens to be a sound suggestion for evaluating new management models. If a consultant or educator offers you a new framework for management, ask what the underlying assumptions of the model are. If the list of assumptions is longer than your arm, you can probably be certain the model is not based on reality. The real world is unpredictable. In an effort to control the unpredictability, models make assumptions. These assumptions are useful in theoretical testing but lose practicality for managers. Assumptions narrow the application range of a model.

So, if a model is suggested, and said model has assumptions, validate those assumptions before adopting the model. Otherwise, you may end up dealing with unintended consequences of your decision.

Induce your decision making. Game theory and other rational model theories are developed through deductive reasoning. A more practical approach to decision making is through a process of induction. Inductive decision making is incremental. For example, imagine that you are a nonprofit executive trying to decide between starting one of two programs. An inductive process demands that you conduct a needs assessment on the populations you serve, assess internal capacity, assess receptivity of funders/donors, and utilize information from previous program launches. Inductive processes begin with the collection of facts from the operating environment (deductive processes assume donors will act in a specific way). These facts can then be analyzed to calculate the best way forward. Inductive processes can be more cumbersome and time-consuming, but you arrive at a decision with evidence and support.

Embrace the abyss of uncertainty. As humans, we have an innate desire to reduce the uncertainty in our lives. At times we are able to reduce uncertainty to risk, or a calculable probability of success or failure (think chances of having a heart attack based on family history, diet, and behavior). Unfortunately, much nonprofit management work requires us to make decisions when there is uncertainty. We are not sure how staff changes will impact productivity or how a new program will impact our reputation among similar service providers. Regardless, using models that assume away uncertainty does not prepare us for the reaction our strategy will cause (good or bad). Instead, utilize decision-making frameworks that account for uncertainty. Develop contingency strategies in the event of negative feedback. Frameworks that embrace the abyss of uncertainty will better prepare you and your organization for unintended consequences, enabling organization survival.

* * *

I started this article with the purpose of debunking yet another rational management model invading nonprofit management. Despite what I believe to be a cogent argument against game theory, the trend of bringing for-profit models into the nonprofit sector continues. Nonprofit management has a great deal to offer our collective understanding of decision making and governance. Surviving on limited resources and operating in multiple stakeholder environments are just two areas in which nonprofit managers have established the standard for effectiveness. But until nonprofit stakeholders view their sector (and its management) as a for-profit peer rather than a pupil, we will be continually forced to respond to this invasion of ideas.

NOTES

- National Center for Charitable Statistics, Quick Facts About Nonprofits, www.nccs.urban.org, accessed April 24, 2012.

- Gandolfo Dominici, “Game Theory as a Marketing Tool: Uses and Limitations,” Elixir Marketing 36 (July 2011), www.elixirjournal.org/articles_view _detail.php?id=1086&mode=pdf.

- Zanie Giraud Voss, Glenn B. Voss, and Christine Moorman, “An Empirical Examination of the Complex Relationships between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Stakeholder Support,” European Journal of Marketing 39, no. 9/10 (2005): 1132–1150.

- Joseph Galaskiewicz and Wolfgang Bielefeld, Nonprofit Organizations in an Age of Uncertainty: A Study of Organizational Change. (New York: Aldine de Gruyter, Inc., 1998).

- Hagen Lindstät and Jürgen Müller, “Making Game Theory Work for Managers,” McKinsey Quarterly (December 2009): 1–9.

- Cagla Okten and Burton A. Weisbrod, “Determinants of Donations in Private Nonprofit Markets,” Journal of Public Economics 75, no. 2 (February 2000): 255–272.

Scott Helm, PhD, is a Senior Fellow with the Midwest Center for Nonprofit Leadership and Director of the Executive Master of Public Administration in the Bloch School of Management at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

To comment on this article, write to us at feedback@npqmag.org. Order reprints from http://store.dev-npq-site.pantheonsite.io, using code 190204.