In the nonprofit sector, disdain for accounting-based measures of overhead as a means of evaluating charitable activities now appears to be universal. At the same time, though, donors continue to rely heavily on those measures, which only amplifies the frustration for those who dislike accounting-based evaluation. Of course, there’s much to dislike about overhead measures. Accounting functional classification of expenses (classification between programs, fundraising, and administrative costs) is only an estimate of where resources are going, which means it is not perfect, and recent cases of cost allocations gone awry are among the many circumstances where the intent of accounting standards and their implementation diverge notably. Even if it were a perfect reflection of where resources are being used, the functional expense classification afforded by accounting standards stops short of providing any evidence to how effectively they are being used.

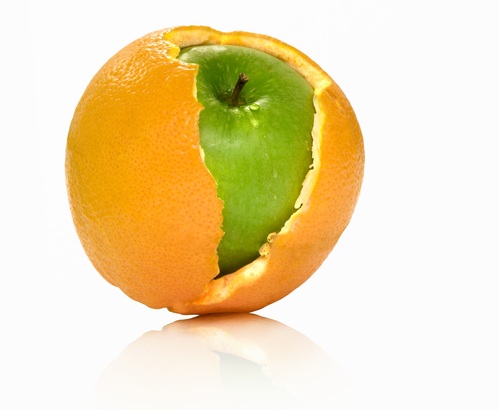

For these reasons, the passion with which many hate accounting measures is often matched by their ardent belief in the promise of impact-based performance measurement. At the risk of sounding like an accounting apologist, I believe the nonprofit sector should be careful what it wishes for when it comes to pushing for evaluating charities based on impact measures rather than accounting measures. I fear that the same voices expressing hatred for accounting may one day redirect their ire toward impact measures, pining for the “good old days” when accounting reigned. As I see it, there are three key things about impact measures that could make the flaws in accounting measures pale in comparison.

Impact measures are less reliable

Measuring impact may give donors information about performance that’s more relevant, but this information will inevitably be less reliable. Such a tradeoff is a key consideration in all types of performance measurement. However, it seems those in the nonprofit sector have focused on getting the most relevant measure while ignoring that tradeoff with reliability.

For all their faults, accounting measures are constructed to be verifiable. Being transactions-based and reliant on a common measurement basis (dollars), the accounting paper trail permits routine auditing by a third-party. Verifiability and independent auditing make accounting-based measures relatively reliable. True, the accounting can only tell us where resources went, not what was gained for society from that allocation of resources. If one cares about reliability, though, it is hard to imagine a systematic way of verifying any claims of societal gains. Take the case of a literacy organization. Whereas accounting measures stop at telling us how much in resources was devoted to literacy efforts, an impact measure could tell us how many individuals were taught to read by an organization. However, imagine trying to verify such claims in an objective and systematic fashion. In other words, the relevance benefit of measuring literacy outcomes inevitably entails a sacrifice of reliability.

These tradeoffs have consistently played out in development of measures in the for-profit sector. For instance, consider fair-value measurements of investments as governed by Statement of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS) 157. In an attempt to provide financial statement readers with better information about the value of a firm’s investments, SFAS 157 requires organizations to develop measures of the value of these investments even if they are not actively traded in markets. The result of the standard was the use of economic models of value, particularly for investments in private equity and real assets. Academic research has confirmed that efforts to develop these “mark-to-model” measures has both increased the extent to which investors have relied on them and, at the same time, made accounting measures of investments less precise. While some have praised the efforts to increase relevance, others have blamed the lack of reliability on perpetuating problems with valuation and even cultivating the financial crisis. It is this issue of sacrificing reliability that nonprofit leaders must grapple if they want to fully embrace impact measures.

Impact measures are less easily compared

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

One overlooked feature of accounting measures for nonprofits (such as the program expense ratio and fundraising efficiency ratio) is that they offer donors comparability across many types and sizes of organizations. Though such comparability is not perfect, it does offer a good starting point for potential donors. It is hard to imagine such comparisons in a world of impact measures. For one, it is often hard to come to agreement on the relevant metrics for different organizations. Even when the relevant measures for two different organizations are apparent, how does a donor compare them? Trying to decide between donating to a literacy group or a homeless shelter based on the number of people taught to read by one and the number of people housed by another is a tortuous exercise in mental accounting. Even two organizations with the same goal of different sizes become hard to compare solely on impact grounds. If one organization is larger than another, we would naturally expect it to have a greater impact. That alone does not mean it is more deserving of donor funds.

Again, these issues have already played out in the for-profit sector. Despite the many complaints about accounting and the concurrent development of alternative qualitative metrics and key performance indicators for internal users, there remains a heavy reliance on accounting-based metrics (e.g., return-on-assets and return-on-equity) by outside investors. True, outside investors may find key performance indicators informative, but they highly value measures that can be compared across a broad swath of firms and industries. As it turns out, accounting metrics usually trump others in this regard. So while the voices complaining about the flaws of accounting are certainly loud, everyone also eagerly awaits quarterly earnings announcements. Perhaps the inherent lack of comparability portends a similar future for nonprofit impact measures.

Impact measures are less controllable

The primary enthusiasm for impact measures is that they capture the ultimate outcomes of charitable activities, that about which we care most. However, the “controllability principle,” a viewpoint now widely accepted both by economic theory and by performance measurement specialists, argues that we should not evaluate individuals or groups based on outcomes per se, but instead based on the aspects of outcomes over which they have control. The theory advocates that using controllable measures is particularly important when those being measured are averse to taking risks, a phenomenon omnipresent in the nonprofit sector.

With this in mind, consider again the question of accounting vs. impact measures. The accounting-based program expense ratio does not tell us perfectly about a nonprofit’s effectiveness, but it is certainly controllable. It is up to the discretion of a nonprofit’s management about where to devote its resources, and that is primarily what is measured (even if imperfectly) by the functional classification of expenses. Program outcomes are another matter altogether. One literacy organization may have greater success in teaching people to read than another because it had students who were on the cusp of reading and able to focus exclusively on learning, whereas another organization’s students were far from ready and facing a variety of other problems. Is it fair to say the organization that had more “teachable” students was better?

Even worse is the concern that organizations evaluated based on these impact measures will seek out circumstances that are more apt to lead to successes. As an example, a fixation on survival rate measures among cancer hospitals is the backdrop for the accusation that the Cancer Treatment Centers of America screens patients and turns away those who are less likely to be treatable. Since nonprofits serve as a societal safety net, it becomes all the more important that they be rewarded rather than punished for seeking out the difficult cases.

Again, a for-profit analog to the problem is instructive. Firms that focus solely on outcome-based performance measurement often see a concomitant decrease in research and development (R&D) spending. Though R&D has a substantial upside, there is also the risk of failure. While investors may be willing to take such risks, many being evaluated by outcomes are not, fearing they have little control over R&D successes. To overcome this disincentive to invest in R&D, firms have either tried to make decision-makers less risk averse (say, by limiting their downside via stock options or stock appreciation rights) or to instead reward them for that which they control. The latter choice, which seems more germane to nonprofit performance measurement, entails rewarding R&D spending rather than R&D success. Much the same thinking applies to nonprofits; while rewarding them for spending on programs is only an input measure, it is much more controllable than the output measure of those programs’ success.

Taken together, these concerns about reliability, comparability, and controllability of impact measures suggest the staying power of accounting measures amidst a barrage of criticism is no accident. I realize this defense of accounting measures exhibits the flavor of looking for lost keys near the streetlight because it’s easier to see there. But it does seem like a good place to start. After all, I am not suggesting measuring impact is not worth the trouble. What I am saying is that the notable weaknesses of impact measures are the very things at which accounting excels. For this reason, impact measures are better viewed as a complement to, not substitute for, accounting measures.