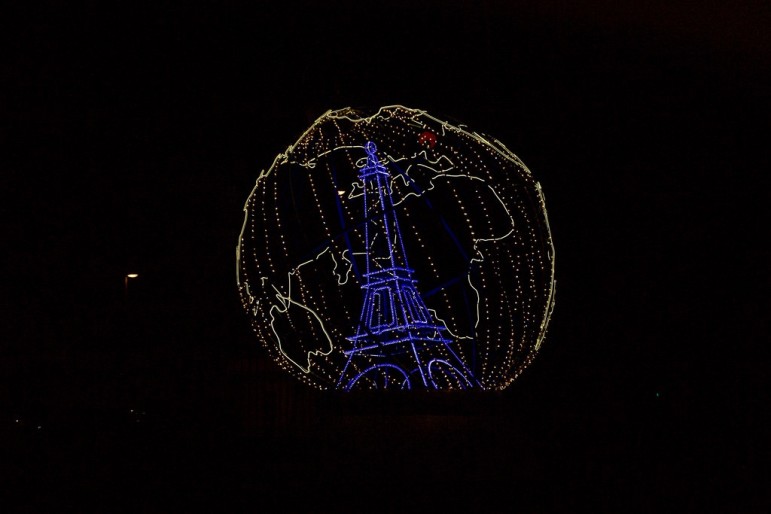

December 13, 2015; NPR, “Environment”

Breaking out the champagne after weeks of grueling negotiations and compromise, delegates of the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris congratulated themselves on achieving what previous talks have failed to do: an international commitment to an aspirational framework that is more ambitious than what was generally expected at the outset. There is indeed cause to, if not exactly celebrate the accords, at least acknowledge the significance of what they have put on the table:

- Universal participation: What is different about this agreement is that it requires all countries, large and small, to reduce fossil-fuel emissions. Developed countries are expected to reduce emissions more aggressively and rapidly developing Southern Hemisphere states are expected to do as much as they can do within the context of their own economies and circumstances.

- A more ambitious goal: Negotiators set out to achieve the difficult goal of limiting the increase in Earth’s average temperature to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Organizations such as the Alliance of Small Island States spoke out early and passionately on behalf of those countries most vulnerable to drastic weather events to set an even more ambitious goal of 1.5 degrees. But it wasn’t until Germany and France signed on, followed shortly by Canada and Australia, that it began to look like the initial 2-degree goal would be adjusted downward. With China, the U.S., and the European Union coming around by Wednesday of last week, the final agreement qualifies the 2-degree goal with a call to “pursue efforts” to limit the increase to 1.5 degrees.

- Homework: Delegates set about cementing targets in their home countries, with a goal to reduce emissions from peak levels by the second half of this century (the U.N.’s climate panel warns of dangerous warming if net zero emissions do not occur by 2070).

- An assessment mechanism: What some consider a big win in the agreement is the “ratchet mechanism,” whereby governments are required to review their targets within four years to adjust them as necessary, spelling out new pledges for 2025 and 2030. This was an important victory for developing countries reluctant to promise too much too soon, particularly if growing their economies depends on the continued use of fossil fuels.

- Financial assistance: By the end of the 2009 Copenhagen climate talks, industrialized European countries and the U.S. had pledged commitments to developing countries of up to $100 billion annually by 2020, although actual amounts expended thus far remain far below that ambitious goal. The Paris agreement does not mandate specific amounts, but Secretary of State John Kerry gained a great deal of attention last week when he doubled the United States’ commitment, pledging $800 million over five years. And wealthier developing countries have agreed to begin contributing on a voluntary basis (a long-time bone of contention), with China pledging $3.1 billion in September to help poor countries finance their own transition programs between now and 2020.

The World Resources Institute writes on its website that “[the agreement] marks a new type of international cooperation where developed and developing countries are united in a common framework, and all are involved, engaged contributors… Cities and forests, business and finance—all these were part of the many initiatives and commitments that were launched or strengthened over the past two weeks. And they will be key to the solution as action moves forward with the energy generated by Paris.”

So what’s not to like? Well, according to several thousands activists who demonstrated peacefully near the Arc de Triomphe on Saturday, carrying dramatic red banners, tulips, and umbrellas, it will require much more than the measures in the agreement to bring about lasting improvement. The agreement requires countries to be highly transparent, and to do what is required to ensure compliance with the terms and with the pledges put forward. But the biggest complaint is that the Paris climate deal is not a treaty and is therefore not enforceable, leaving many to question exactly how countries will be held accountable.

Moreover, most climate activists want to see a commitment to leaving fossil fuels underground. And while the 2-degree pledge is a big step in that direction, in the words of the U.S.-based 350.org, which organized the Paris demonstration, there are “too many loopholes…despite the heroic efforts from leaders of vulnerable nations.”

Though the concerns of developing countries, particularly those low-lying nations suffering the most devastating consequences due to extreme climate events, are recognized in a section of the agreement noting “loss and damage” (or, as Ben Adler in Mother Jones writes, “loss and damage, sort of”), a footnote states specifically that this “does not involve or provide a basis for any liability or compensation.” In other words, a mechanism to address displacement related to climate change and its attendant issues has little or no teeth.

Perhaps most alarmingly, while nearly every country has submitted pledges to reduce emissions and commit to alternate sources of renewable energy, scientists say that even with all these measures in place the world is still looking at 2.7 to 3.5 degrees of warming. Leading climate researchers say this level of increase will have devastating global consequences.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Looking back on two decades of climate talks, George Monbiot in The Guardian thinks the biggest shame is that we have wasted these 20 years:

A maximum of 1.5C, now an aspirational and unlikely target, was eminently achievable when the first UN climate change conference took place in Berlin in 1995. Two decades of procrastination, caused by lobbying—overt, covert and often downright sinister—by the fossil fuel lobby, coupled with the reluctance of governments to explain to their electorates that short-term thinking has long-term costs, ensure that the window of opportunity is now three-quarters shut. The talks in Paris are the best there have ever been. And that is a terrible indictment.

There will be countless analyses in the coming weeks from people who were on the ground in Paris, environmentalists, practitioners, finance types, entrepreneurs, and other observers with both personal and financial stakes in the proceedings and outcomes. It’s highly unlikely that one clear consensus will emerge as to the question of whether we are going to be okay. But as Robinson Meyer writes in The Atlantic, the answer to that question is more complicated than yes or no.

“If climate change worries you, think about not only how you vote, but also how you spend your civic attention and how you communicate your concern to policy-makers. Think too about how you’re supporting those already affected by it.

“To my mind, climate is our great story. No other narrative envelopes all of humanity in quite the same way, forcing answers about the ethics of food, of oil, of technology, of economic security, of democratic republics and command capitalism, of colonialism and indigenous peoples, of who in the world is rich and who in the world is poor.

“We live in the middle of history. Nations still bicker over borders, flaunt weapons of mass death, and abhor refugees in their midst. In Paris, they tried, miraculously and inadequately, to care for their common good.”

Indeed. We live in a time when it sometimes feels as though we are on the verge of a dystopian, post-apocalyptic future. So it is truly miraculous that over the past two weeks we could find a modicum of shared humanity in that which intimately connects us all. — Patricia Schaefer