February 3, 2016; Latin Post

As reported here last month, the Obama administration began the new year with a wave of deportations directed at Central American migrants who have recently arrived in the U.S. Targeting newcomers from countries in what is referred to as the “Northern Triangle” (Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala), the Department of Homeland Security confirms that 121 immigrants have been detained, mostly women and children.

While small in scale (the U.S., after all, has deported more than 2 million individuals under the Obama administration alone), immigrants and activists are shaken by these recent raids because they are focused on women and children who would be returning to countries marked by unprecedented violence, forced conscription into street gangs, instability and political corruption, circumstances that made them flee to neighboring countries and, ultimately, the U.S. in the first place.

Schools from Maryland to California are reporting that parents are keeping their children home, and workers fear they will never see their families again if Immigration and Customs Enforcement decides to raid their places of employment. Joanne Lin, the immigration policy advocacy counsel at the ACLU, told ThinkProgress that immigrants from these countries in particular have reason to be afraid, as at least 83 people since 2014 have been reportedly killed after they were deported back to the three countries.

The question immigrants and advocates are asking the administration is why, given what we know about the situation in Central America and the diplomatic steps we are taking to address it, we are stepping up raids on the very people we are trying to help.

According to some experts, administration officials are pursuing the deportations because they are afraid that inaction will undermine their legal rationale for the executive action programs President Obama announced in 2014 to defer deportations for certain undocumented children and parents of U.S. citizens. The administration’s legal rationale for the actions is based on “prosecutorial discretion.” This means that government agencies can decide when to prosecute based on a system of priorities. Homeland Security’s deportation priorities, announced at the same time as the president’s actions, include the removal of felons, people with terrorist ties and recent border crossers. The women and minors rounded up in the most recent raids fall squarely into the latter category.

While the typical narrative of immigrants in the past has been the pursuit of good jobs, better economic opportunities and future for one’s family, that story has changed dramatically since 2014, when the numbers and countries of origin began to shift.

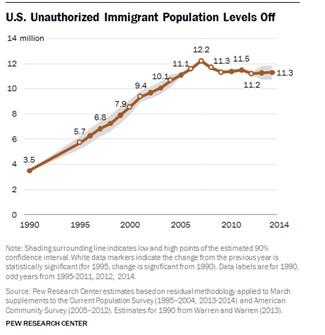

A recent study by the Center for Migration Studies (CMS) finds that the population of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. has fallen below 11 million for the first time since 2004. While a Pew Research study published over the summer reports a slightly higher number (11.3 million), both reports conclude that, contrary to popular opinion that the numbers of people entering the country illegally is at an all-time high, the population has decreased since 2007 and 2008, and has in fact stabilized over the last five years.

A recent study by the Center for Migration Studies (CMS) finds that the population of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. has fallen below 11 million for the first time since 2004. While a Pew Research study published over the summer reports a slightly higher number (11.3 million), both reports conclude that, contrary to popular opinion that the numbers of people entering the country illegally is at an all-time high, the population has decreased since 2007 and 2008, and has in fact stabilized over the last five years.

Both reports cite declines in the number of Mexican nationals living in the U.S. since 2009. Pew attributes the decline to several factors—the economic market since the Great Recession, stricter enforcement of immigration laws, increased stability in the country and, most significantly, family reunification, which 61 percent cited as their reason for returning to Mexico.

CMS research also identifies growing naturalized citizen populations in almost every US state and cites findings that, since 1980, the population of foreign-born legal residents from Mexico has grown faster than the undocumented population from that country. These trends, according to CMS executive director Donald Kerwin, “should be applauded by partisans on all sides of the immigration debate.”

According to Michelle Brané, Director, Migrant Rights and Justice Program at Women’s Refugee Commission, what’s most interesting about the CMS research is that it quantifies what immigrants and advocates have long suspected: That while there has been a net decrease between 2010 and 2014 in the number of undocumented immigrants from Mexico and countries in South America and the Caribbean, numbers have increased from the Northern Triangle countries of Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala.

“This is not a question of strict border security,” she says. “These are kids and women who are essentially turning themselves in. They’re not sneaking over a fence, rather, they’re presenting themselves to the border and asking for protection.” (This is a fact also acknowledged by Steven Camarota at the Center for Immigration Studies, which advocates for lower overall immigration).

Brané sees this as a positive sign. “When you think about it, it means the system is working. As asylum seekers, they are appropriately exercising their legal right to present themselves to Border Patrol and ask for protection.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

There is no question that the newest wave of women and unaccompanied children are fleeing an extraordinary combination of violence, organized crime and corruption. The murder rate in El Salvador alone increased 70 percent between 2014 and 2015, with 104 victims per 100,000 citizens. Overall, as Vicki Gass of Oxfam America wrote last month, violent deaths in Central America rose from 15,727 in the same timeframe:

[Children and families from this region] pose no threat to national security. Instead, the president should acknowledge the driving factors forcing people to flee their homes, and reconfirm the U.S. government’s commitment to address the root causes of violence, hunger and unemployment in Central America.

Violence directed against women, while severe across the region (not to mention globally) is particularly acute in Guatemala. The country ranks third in the killings of women worldwide, and according to the United Nations, two women are murdered every day. WRC’s Michelle Brané says that prosecutions for femicide (the killing of a woman based on the fact that she is female) are less than one percent.

Under pressure from members of Congress and advocacy groups, the Obama administration is working with UNHCR to resettle Central American refugees and recognizes, in the words of White House spokesman Peter Boogaard, the need to provide a “safe and legal alternative to the dangerous journey many are currently taking in the hands of human smugglers.” The office of the UN high commissioner for refugees will conduct initial screenings to test whether people from Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala may qualify as refugees, but the final decision will rest with the U.S. government, based on the criteria it applies under existing refugee admissions programs.

While no final figures have been given, the U.S. ceiling for refugees this year is 85,000, which includes 10,000 Syrians. It’s estimated that the recent measure would allow up to as many as 9,000 migrants each year from the three countries to eventually settle in the United States or other countries in the hemisphere.

The expansion of resettlement opportunities is one part of a broader response to address the crisis in the three nations, which also includes a recent visit by Vice President Biden to the region and $750 million in developmental aid to help the Central American governments stabilize the region by strengthening the police force and justice system, and funding violence prevention, literacy and vocational education programs.

In the meantime, according to Church World Service, at least 50 churches are gearing up to offer refuge to Central Americans with deportation orders. As reported in the LA Times this week, a growing number of religious officials are beginning to revive the sanctuary movement:

The recent immigration raids were simply the “tipping point,” said Alexia Salvatierra, a Lutheran pastor in Los Angeles who teaches and trains faith-rooted organizing across the country. “It was basta—enough,” she said, summing up the general feeling toward the raids among some in the faith-based community in Southern California.

Not all in Congress are willing to let the issue continue to languish and champions for the refugees are making their voices heard. Twenty-two Democratic senators wrote a letter to the president, calling the raids predicated on “a false premise that most of these people are not fleeing extraordinary danger.” Last week, Illinois Representative Luis V. Gutiérrez spoke before his fellow lawmakers, imploring them to focus on young and unaccompanied asylum seekers from Central America. Chastising those who would blame the problem in its entirety on the President, he tossed the football back in their court:

The home raids announced by the Obama Administration around Christmas have struck a nerve. They have sparked rumors and panic and have multiplied as city after city have experienced raids or the rumors of raids…The fear and anxiety has nothing to do with Donald Trump or the fantasy that he has of deporting millions of immigrants or barring people from this country because of their religion. The fear and anxiety is born of decades of congressional inaction and leaders in Washington hoping that the problem would just go away…

For all of the Americans that want a legal and accountable immigration system and all of the families that fear a knock on their door, this Congress again seems to have nothing—and to do nothing other than let the demagogues and fear rule the day.

—Patricia Schaefer