April 4, 2016; New York Times

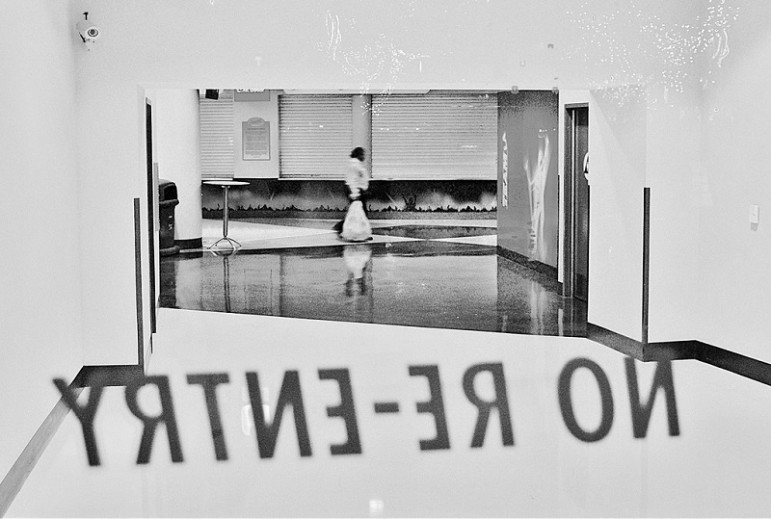

“Reentry” is the word for the emerging issue of finding jobs and homes for “returning citizens”—which is to say former inmates. The issue field is actually broader than just persons who are recently released and includes anyone who is denied work or housing because of a criminal record. The success of the “Ban the box” movement of the past couple years has overshadowed the equally significant problem of finding housing. Discrimination against persons based on criminal background is a well-known and widely accepted practice. However, as the U.S. moves to correct the policy catastrophe of mass incarceration, more and more returning citizens will be seeking to reunite with their families and integrate into communities.

HUD took a small step towards suggesting that blanket policies barring housing to returning citizens might be illegal. The New York Times announces, “Federal Housing Officials Warn Against Blanket Bans of Ex-Offenders” in reporting on HUD Secretary Julian Castro’s warning to landlords to discontinue so-called “one strike” rules against renting to formerly incarcerated persons. But, wait…what’s new here?

Secretary Castro’s statement and the new HUD guidance do not create a new protected class for ex-offenders under the Federal Fair Housing Act. Only Congress or a state or local legislature could extend that kind of protection. In fact, the Castro warning and the new HUD guidance reiterates what’s been settled policy at HUD’s Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity (FHEO) section for some time. The basic principle is, if the application of a rental policy has a disproportionate impact on a class of home-seekers who are protected under the Federal Fair Housing Act, then the policy could be discriminatory, even in the absence of “intent” to discriminate. The Times quotes Secretary Castro from a prepared statement saying, “Right now, many housing providers use the fact of a conviction, any conviction, regardless of what it was for or how long ago it happened, to indefinitely bar folks from housing opportunities.”

The concept of “disparate impact” has a controversial history over the last five decades during which the Fair Housing Act has been the law of the land. However, last year’s Supreme Court decision in Texas v. Inclusive Communities upheld the principle of disparate impact, though with some court-suggested guidelines.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

For reentry advocates who have anticipated strong leadership from HUD, the new guidance is another instance of thoughtful equivocation that dates back to Secretary Donovan’s 2012 letters to public housing directors and private owners. In both documents, then–Secretary Donovan recommended (but did not require) federal housing providers to exercise discretion instead of “one strike” type policies. Then, six months after a stinging letter to HUD from Representative Maxine Waters decrying HUD’s “one strike” policies, HUD issued guidance suggesting that there never was a “one strike” policy for former offenders.

HUD does not require that [public housing agencies] and owners adopt or enforce so-called “one-strike” rules that deny admission to anyone with a criminal record or that require automatic eviction any time a household member engages in criminal activity in violation of their lease. Instead, in most cases, PHAs and owners have discretion to decide whether or not to deny admission to an applicant with certain types of criminal history, or terminate assistance or evict a household if a tenant, household member, or guest engages in certain drug-related or certain other criminal activity on or off the premises.

And now HUD offers a “dog whistle” to private nonprofit fair housing agencies to bring cases that fit the blanket bias description. A staffer at a private enforcement agency has said in a private conversation that she has a “disparate impact” case in hand, and maybe in two to four years, she’ll have a decision. The NYT article notes that the key case in this area of the law has been in Federal Court since 2014. In the meantime, HUD can skip over doing any real enforcement of its own.

Could Democratic Party politics explain HUD’s soft-pedaling on this issue? The power of the private prison industry in preserving policies of mass incarceration and recidivism is inextricably tied to the Clinton political machine. President Bill Clinton was present at the creation of the era of mass incarceration, and the private prison industry is heartily supporting frontrunner Hillary Clinton. It is also clear that Julian Castro’s appointment as HUD Secretary in 2014 was an effort by the Obama administration to raise his national profile as he was being shortlisted as a vice presidential prospect. So check the boxes. Secretary Castro stays in the news with an announcement around a popular progressive issue that will not offend his patron’s financial backers.

Meanwhile, local movements to open up housing for returning citizens are growing fitfully around the country as citizens and social service organizations wonder where the Federal leadership on the issue will come from. No wonder housing providers don’t seem too worried by the new HUD initiative. The Times quotes landlord attorney Neil Garfinkel saying, “I always advise a holistic approach and to look at the applicant as a whole.”—Spencer Wells