May 23, 2016; Chicago Sun-Times and Catalyst Chicago

The school year for Chicago’s public schools will end about four weeks from now. While state and local politicians argue and point fingers about who is to blame, the financially challenged school system is struggling to decide what it will look like when school begins next fall.

Chicago Public Schools (CPS) began this year faced with a strapped operating budget, which needed to be shored up with $1 billion of new debt. Midyear, it was forced to further reduce expenses by more than $400 million by imposing unpaid furlough days on staff and cut some personnel. Its severely underfunded pension plan still needs a $9.5 billion payment for which there are no funds. District city leaders began the year hoping that financial help would come from the state government, but the state has not responded.

The current projection for next year’s budget, which must be balanced and approved by the beginning of August, sits with a $1 billion hole to be filled. On top of this remains the need to finally negotiate a contract with their teachers, who have worked this school year without a contract and have threatened to strike if no contract is in place.

Forest Claypool, the district’s CEO, described the situation to the district’s board as “the point of no return. There’s no question, without equal funding from the state, these cuts will be extreme.” District spokeswoman Emily Bittner described what “extreme” means on a local school level: “On average, schools will feel a budget cut of 26 percent once they receive their state and federal funding. The base per-pupil rate will drop from $4,088 to $2,495 if the proposed budget becomes final.”

If no silver bullets are found, a very different school system will await Chicago’s children next fall. Andrew Broy, president of the Illinois Network of Charter Schools, told Catalyst Chicago that “the scope of the cuts they’re talking about—20 to 25 percent, in that range—would really be a death blow to a number of [charter] schools, no doubt about that. We’ll see dozens of charters [sic] schools not be able to open in the fall.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

As many as 15,000 students will need to find a new school. It is also possible that those applying for new charters will reconsider their plans for opening this fall. While charter schools can decide the situation is too difficult and close their doors, the district’s traditional public schools cannot, and they will have to find a place for those children despite the limited funding available.

D’Andre Weaver, principal of Gwendolyn Brooks College Preparatory Academy, is preparing to reduce his school’s expenses by $520,000—or more than $1 out of every $4 previously allocated to the 900-student school. He told the Chicago Sun-Times, “You can’t do a lot to make that easy. You’re going to have to cut people, and it’s going to impact the classroom. There’s no way around that.” Having five or six fewer classroom teachers may be his only option.

Across the district, principals are now working on figuring out this puzzle, hoping to find solutions that do the least harm to their students. Efforts in the state capital to find a way to help Chicago’s public schools avoid these drastic reductions remain stalled in the ongoing battle between Republican Governor Bruce Rauner and the Democratic-controlled state legislature that has left the state without a budget for almost 11 months and caused the state to miss the deadline for approving a budget for next year. Proposals to create a new statewide funding formula for public schools and to have the state assume responsibility for the Chicago Teacher’s Pension Fund, which would give Chicago several hundred million dollars of new funding, will not be acted upon as long as the state’s budget remains in limbo. Even if a budget compromise is reached at the state level, it is very possible that Chicago’s public schools will not get the funds they are hoping for.

At a city level, Mayor Rahm Emanuel has kept his eyes on the fix coming from Springfield and remains opposed to raising city taxes or to tapping available TIFF funds for use by the school district.

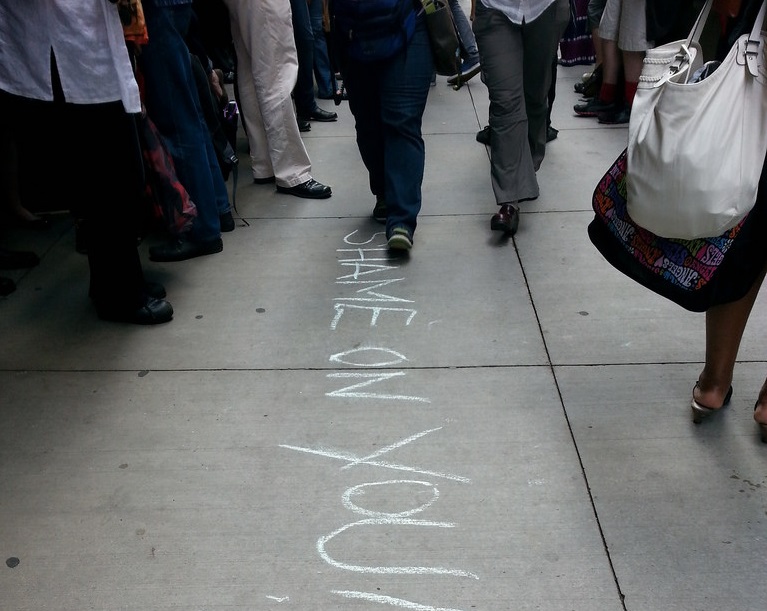

The Chicago Teacher’s Union, according to the Chicagoist website, sees politicians ignoring additional tax revenues as a way to fix the financial problems.

Mayor Rahm Emanuel, Gov. Bruce Rauner, and CPS CEO Forrest Claypool [are] unwilling to use other revenue to boost cash-strapped budgets. Policy suggestions include closing corporate loopholes, creating a progressive income tax or taxing LaSalle Street trading. “Chicago Public Schools are breaking on purpose,” CTU reps wrote in a statement on Monday. “Claypool won’t dare approach his boss or his wealthy backers for the funds our students desperately need.”

A year ago, it seemed inconceivable that these leaders would allow the state to operate without a budget and without addressing its significant fiscal problems. But 11 months have gone on without any agreement. Will they also be willing to hold 400,000 Chicago school children hostage as they battle? The net few weeks will give us their answer.—Martin Levine