December 29, 2016; New York Times

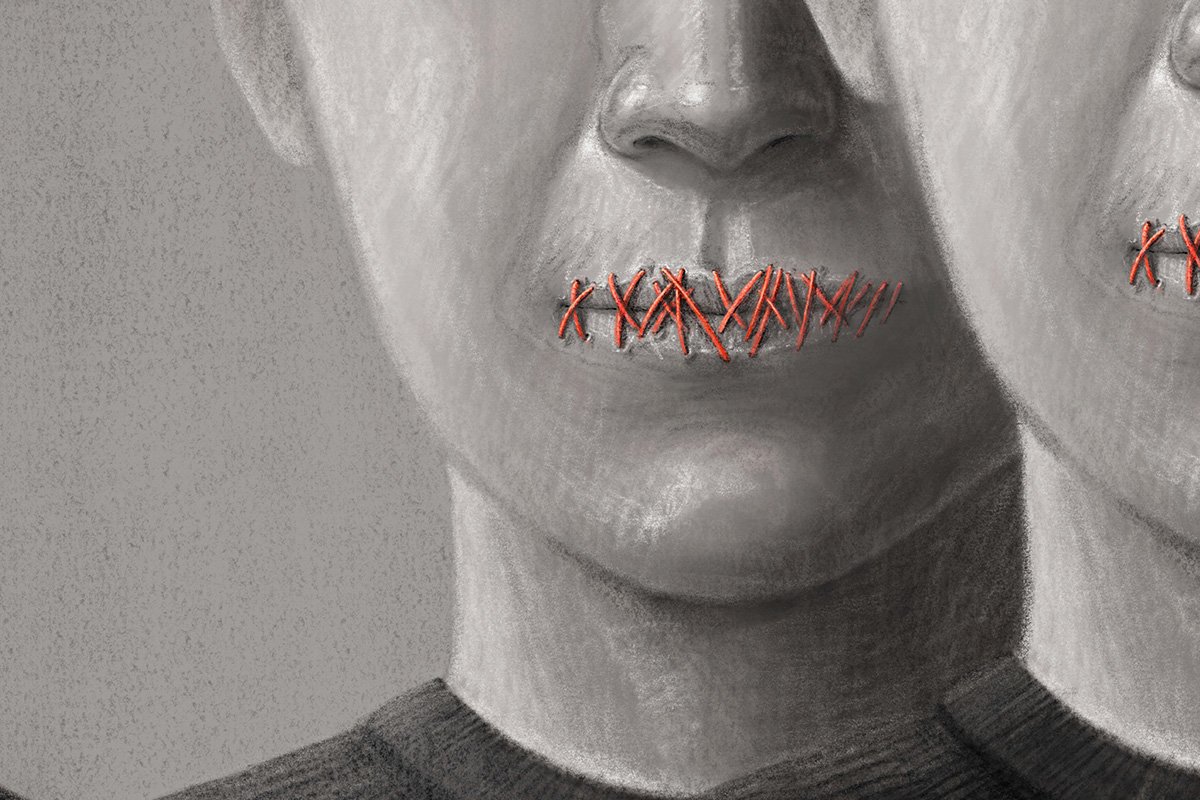

We’ve heard all about fakes this year: fake scandals, fake food, fake news. Now fraud emerges from a somewhat unexpected corner: academia—or rather, its counterfeit. Fraudulent academic groups have been soliciting papers from researchers for conferences and journals, but do not adhere to publication standards like peer review; instead, they accept papers unquestioningly and charge authors enormous fees.

One of the more notorious perpetrators of this type of scam is OMICS International. It is run by Srinubabu Gedala, who has been accused of plagiarism in his own academic work. OMICS and two affiliated groups, iMedPub and Conference Series LLC, are currently being sued by the Federal Trade Commission for “deceiving academics and researchers about the nature of [their] publications and hiding publication fees ranging from hundreds to thousands of dollars.”

Jeff Beall, a research librarian at the University of Colorado in Denver, has published a notorious blacklist, known as “Beall’s List,” of what he calls “predatory open-access journals.” He also published a list of tips for recognizing fraudulent publications, including boastful language or failure to vet reviewers. There are over 4,000 publications on Beall’s list, including OMICS, which threatened to sue Beall for $1 billion in 2013.

Sometimes, the lack of academic standards makes itself immediately obvious. For example, this fall, Professor Christopher Bartneck of the University of Canterbury submitted an abstract that he wrote using the autocomplete option on his iPhone. His website openly states, “The text really does not make any sense…[the paper] was accepted only three hours later!”

Other times, a façade of legitimacy lures in otherwise reputable names. James White, a plant pathologist at Rutgers, unwittingly joined the board of an OMICS journal called Plant Pathology & Microbiology. Shortly afterward, he found that he had been listed as an organizer and speaker at a conference called Entomology-2013, which is also run by OMICS. The conference is a dupe that almost shares a name with the respected gathering Entomology 2013 (no hyphen), which is run by the Entomological Society of America.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“I am not even an entomologist,” said White, who had not been consulted and was neither an organizer nor a speaker.

Getting listed at fraudulent or non-credible events and publications can be embarrassing and potentially damaging, but there’s a more immediate problem with this type of scam: It costs a lot. OMICS and other groups charge enormous publication and conference fees. That’s unusual for academia; it’s also especially problematic because the demographics most eager to publish are also the most financially vulnerable. Post-docs, PhD students, and junior or adjunct faculty must publish and present to advance their careers but are usually paid next to nothing, making the fees burdensome.

According to the FTC lawsuit, “In many instances, consumers only discover that their articles will not be peer reviewed and that they owe fees ranging from several hundred to several thousands of dollars after [OMICS and others] inform them that their articles have been approved for publication. Consumers’ attempts to withdraw their articles are frequently rejected, thereby preventing them from publishing in other journals.” (Publishing a paper in more than one journal is frowned upon and sometimes outright prohibited.)

There are many problems with this situation. One is the plain fact that vulnerable would-be academics damage their bank accounts and their credibility by entanglement with predatory groups. Another is the genuine difficulty of distinguishing between a worthwhile conference and a scam; if a conference lists a prestigious organizer or keynote speaker, the only way to find out if that person is really part of the event may be to call and ask.

A third issue is the damage to the trustworthiness of academic sites, and the added work of distinguishing worthy and useful information from inflated babble. At a time when news sites, research boards, and other public sources of information are being attacked as fake or unethically motivated, and academia is undergoing shifts in funding and support, an added layer of shade makes it even more difficult to establish credibility with the public at large. Peter Dreier, chair of the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College, said more pointedly, “American higher education is under attack by pundits, plutocrats and public officials who believe that many professors don’t work hard and that what they produce is of little value to society.” Nonsense abstracts written by an iPhone and published in credible-sounding journals only make the problem worse.

The FTC deserves appreciation for its defense of vulnerable adjuncts and its recognition that academic standards and practices are violated at great cost to the academic community. This odd and insidious scam technique hasn’t gotten the same attention as the fake news problem, mostly because news has a vastly larger readership than academic papers. However, regardless of readership size, it’s important to distinguish between real information from credible sources, and nonsense or propaganda.—Erin Rubin