March 6, 2017; KUT-FM (Austin’s National Public Radio)

No one would deny that artists, especially musicians, have contributed greatly to the success of Austin, Texas. But as often happens after artists help to put a city—or a neighborhood—on the map, those artists can no longer afford to live and work in the places they lifted up, so they get squeezed out. In Austin, as in other cities, some artists are finding ways to buck this trend by finding “home spaces,” or at least regular performance venues, in historic places of worship. Those often-large-scale sacred spaces are looking for ways to remain relevant in their communities even as their congregations shrink or even disappear.

For example, the Congregational Church of Austin, led by Pastor Tom VandeStadt, has many spaces that are empty for much of the week and a sanctuary that seats 120. He sees the church as offering “an old, comfortable, warm feeling—an intimate environment,” and he can imagine a theater company feeling very much at home there. He sees the potential in his church and his congregation being able to “support artists in the community, support their creativity.” In a boomtown like Austin, there is some urgency in the equation of finding affordable spaces for artists.

NPQ has already covered the creative reuse of sacred places by nonprofits in general and reported on the emerging trend of artists working in such spaces.

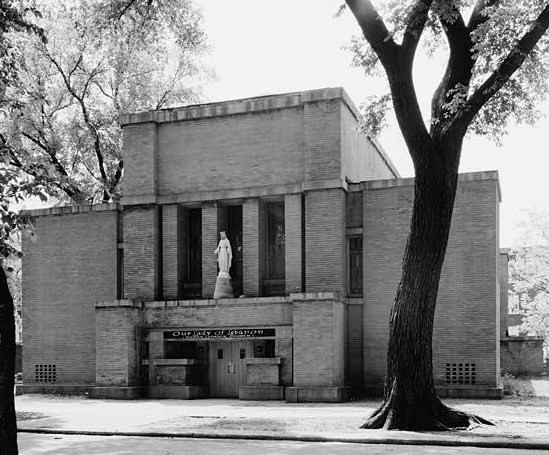

The nascent effort in Austin to identify sacred spaces and fully gauge the interest of faith communities in sharing unused or underused facilities with performing artists or arts groups was sparked by a recent three-city study undertaken by the Philadelphia-based nonprofit Partners for Sacred Places and the Drexel University Westphal College of Media Arts & Design. The research grew out of a Partners pilot program called Arts in Sacred Places, which has facilitated “long-term, mutually beneficial space-sharing relationships” between arts groups and historic places of worship in both Philadelphia and Chicago. The research project took a close look at the needs and perceptions of the arts communities as well as surveying the perceptions of faith leaders and exploring available spaces in historic places of worship in Austin, Baltimore, and Detroit.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Among the common themes uncovered in the research report, Creating Spaces: Performing Artists in Sacred Spaces, across the three cities were these:

Artists

- Performing artists perceive having a “home space”—as opposed to a nomadic existence—as a meaningful way to anchor their work in a community. They also appreciate that having a steady home, or at least a consistent venue that can be used for performances rather than continually scrambling to book affordable spaces, frees up time and energy for making their art. They can imagine that working in historic sacred spaces would improve the experiences they can offer to their audiences, compared with other affordable (and sometimes shabby) performance spaces.

- Artists resist any form of censorship and see their artistic freedom as paramount; in focus groups, many artists expressed concerns that religious organizations would try to censor their work, and that was a perceived barrier to performing or setting up shop in such places.

- Artists would welcome a program that would help them find affordable or donated facilities in historic sacred spaces; on their own, they felt uncertain about how to identify and approach faith leaders to discuss their work and ask about the possible use of facilities.

Faith Leaders

- Significant unused/underused space is available in houses of worship: Including only the six historic sacred spaces studied in detail in each of the three cities, the available space in Austin was more than 72,000 square feet; in Baltimore, more than 42,000 spare feet; and in Detroit, more than 18,000 square feet. In each city, several other additional sacred spaces were willing to participate in the study but were not within the scope of the research design, so the actual numbers are likely much higher. In some instances, these facilities could become “home spaces” for arts groups; in others, they could offer rooms for rehearsals and performances on a regular basis, alternating with the congregations’ activities or other community events.

- The stewards of historic sacred spaces are very much interested in forging stronger links to their communities; with increasingly smaller congregations using the spaces for worship, faith leaders and their faith communities want to remain relevant and be of service to their neighbors.

- Lay and clergy leaders in the sacred spaces included in the study were not terribly concerned about artistic content and were disinclined to censor the art being presented. Perceptions within the artistic community regarding censorship were largely unfounded, but nevertheless could present barriers unless there’s a program or process in place to foster dialogue and facilitate the working relationships. (In Austin, the city’s Cultural Arts Division is in the early stages of filling this role and determining next steps.)

Although many common threads were identified across the three cities, the researchers found differences, too:

While the stated findings demonstrate the common themes among performing artists and historic sacred spaces in all three cities, each city is unique in a variety of ways. These unique elements impact both performing artists and the sacred spaces. In Austin, a key issue is rapid growth and its impact on the real estate market; in Baltimore, a key issue is the role that artists can play in underserved neighborhoods; while in Detroit, a key issue is the do-it-yourself (DIY) spirit of artists and the wealth of vacant spaces.

In addition to these broad characterizations of the differences, links to a series of white papers describing the findings in each of the three cities may be found within the report.

In addition to its work with arts communities and faith communities in Austin, Baltimore and Detroit, Partners for Sacred Places recently released an in-depth analysis of the “economic halo effect” of historic places of worship in three U.S. cities—Philadelphia, Chicago and Fort Worth. The “civic value” of having—and maintaining—these sacred places in urban neighborhoods is extraordinary, whether they are being used by 21st-century congregations, artists or any variety of nonprofit and/or for-profit entities.—Eileen Cunniffe