June 16, 2017; Sacramento Bee

Executive compensation remains one of the most highly scrutinized activities in the nonprofit sector, yet is often described by only one data figure, the dollar amount on compensation, and not in context of the organizational budget or in comparison to other sectors.

Media outlets and watchdog agencies love to compile lists: a Top 25, a Top 50, even a Top 100. Only the Minnesota Star Tribune list even brings up revenue and expenses and allows you to search by subsector for comparisons. Of note in the Minnesota example, 21 of the top 22 are in health care, where state law currently requires health maintenance organizations to be incorporated as nonprofits. Healthcare is generally followed by higher education institutions (lovingly referred to as “the meds and eds”) for top compensation, with large social service agencies and museums close behind.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Due to general over-reliance on only one data point from IRS Form 990 filings, these oversimplified lists don’t tell the whole story of the changing nature of nonprofit organizational revenue streams. Members of the general public are often surprised to learn that today’s nonprofits overwhelmingly earn their revenues from an earned-income business model, as opposed to mere grants and gifts. The Urban Institute, based on 2013 data, puts the earned-income to gifts ratio at an almost 80-20 split. Advocates of the sector need to be able to move the public perception from one of church basement, all-volunteer-run organizations to today’s picture of the sector being made up of larger, more highly complex, and professionally-run organizations.

Further, nonprofits have the right, like all businesses, to compete in the marketplace for the skills, abilities, and talents needed to run their organizations. Increasingly, executive search firms are looking for nonprofit leaders with advanced degrees and “business” skills. One foundation executive, speaking to a roomful of nonprofits, once encouraged nonprofit leaders to seek out board members from the corporate sector because “they bring sharper pencils.” While being both condescending and dismissive to the sector, his comments relay an often-heard message in the sector that “nonprofits should be more like business.” This pithy advice, however, does not hold up well with donors and the public who clearly hold nonprofits to a higher standard. Numerous “best practices” strategies for setting executive compensation are touted by such entities as GuideStar, BoardSource, and the National Council of Nonprofits in an effort to self-regulate.

But guess what? For-profit executive salaries are going up too! International consultants at KPMG report that over the last five years, “Total CEO pay continues to grow, with larger companies paying significantly more than smaller ones.” Even President Trump, someone not known to want to embellish a government role in citizens’ lives, wants to raise federal worker salaries, albeit not necessarily in line with ratified union contracts.

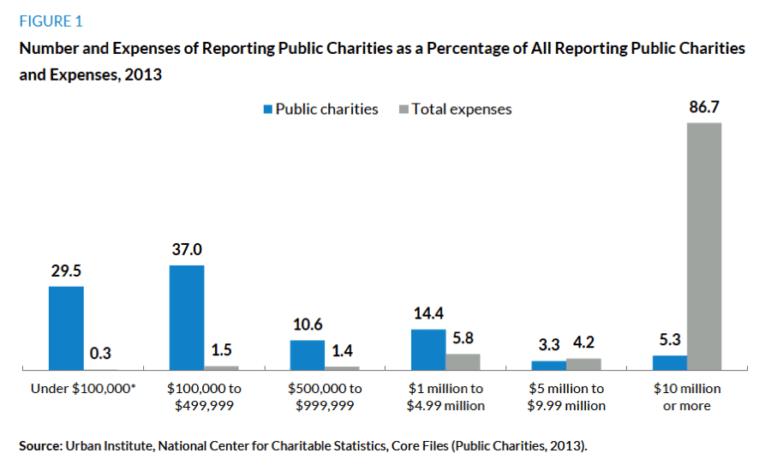

The truth is, all sectors—government, private, nonprofit—want to recruit and retain the best workers for today’s challenges. The nonprofit sector would do well to better educate the public and the media on the realities of today’s complex nonprofit economy and the skills needed to operate these organizations, keeping in mind both efficiency and ethics. And, if we don’t stay united as a sector, this growing divide within the sector threatens to split nonprofits along the lines of size. What might be more worth scrutinizing is the concentrated wealth occurring in nonprofits. While over 77 percent of all public charities have annual budgets of less than $1 million, the remaining 23 percent of organizations control well over 96 percent of the flow of charitable dollars. These might be figures worth looking at.—Jeannie Fox