This article is from the Summer 2017 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “Nonprofit Graduation: Evolving from Risk Management to Risk Leadership.”

Mary hung up the phone, stunned by the news that her nonprofit’s largest funder was dramatically reducing funding because of a change in giving focus. This funder’s annual gift, which comprised 60 percent of the organization’s annual revenue, was crucial to funding the non-profit’s renovations to its newly inherited building, making it safe for the public. This building, an unimaginable gift that had arrived twelve months earlier, would enable the historical society to revive its programs and better serve its community. Now the dream of its renovation seemed impossible, and the additional fixed costs that the building represented made it a threat to the organization’s survival rather than an opportunity for expansion.

Mary’s story is far from unique in the nonprofit sector; in fact, it is extremely common. While we most often hear dramatic stories about the closures of large nonprofits that affect thousands of clients and hundreds of employees—as in the case of Federation Employment and Guidance Service Inc. (FEGS)—nonprofits of all sizes and issue areas are challenged with risks on an ongoing basis.1 Foundations decide overnight that their attention and money are needed elsewhere, and governments at every level decide anew their priorities each time an administration changes hands; loss of funding can happen at the worst possible time. Events like this devastate not only the organization in question but also its clients, its employees, and its donors.

To fully engage with risk questions, nonprofits need to take an intentional approach and become more strategic in their consideration of their own business model—how mission and financial sustainability interact—and their specific contexts. For example, board and staff need to become intimate with the dynamics of the organization’s budget and the relationships and circumstances that underlie those dynamics. Similarly, to have a true understanding of how best to engage with the most critical risks, nonprofits need to push themselves to understand on the one hand how all areas of operation interrelate and affect mission achievement and on the other hand how to maximize opportunities—by intentionally taking risks—that will further mission achievement and organizational sustainability. Only in this way can they responsibly engage with risk and opportunities—linked as they so often are.

Why Risk Leadership Matters

In a sector in which risk is inherent and uncertainty is a constant—particularly as we see more changes coming out of Washington—identifying and engaging with risk have never been more important for nonprofits. Not doing so undermines our sustainability, along with the well-being of the people we serve.

Even before the November election, numerous examples of nonprofit closures confirmed the need for nonprofit boards, leaders, and staff to better understand how to identify, assess, and engage with risk. We have seen this in our work at Community Resource Exchange (CRE) as our client organizations grapple with challenges such as inconsistent funding or multiyear contracts with flat funding, capped overhead rates, changing community needs, and increasing demand, to name a few. This manifests in real-life examples, such as a $14 million local workforce-development agency that had to close its doors after suffering a massive loss in cash. The cash loss followed from investment in a new office at the same time that a major grant was cut. Combined, these losses made it impossible to weather the shocks, given the nonprofit’s already tenuous financial health after years of overreliance on government funding. Another example is a youth-serving organization that is now pursuing a merger to preserve core services after losing its 501(c)(3) status as a result of failing to file its 990 or fulfill basic contract commitments—all of which might have been avoided had the board been informed and proactively engaging with risk all along. From these organizations, as well as nonprofits that are performing well, we’ve seen a desire to learn more about risk and not only how to intentionally manage it but also how to make the switch from risk management to risk leadership. For example:

- Between 2015 and 2016, New York’s Human Services Council (HSC) brought together thirty-two seasoned human services executives, social sector leaders, and experts in nonprofit management to form its Commission on Nonprofit Closures. This group recommended, among other things, that nonprofit boards and staff “be engaged in risk assessment and implement financial and programmatic reporting systems that enable them to better predict, quantify, understand, and respond appropriately to financial, operational, and administrative risks.” Assessing, managing, and mitigating risk was identified as a crucial endeavor for all nonprofits, regardless of size, age, or issue area.2

- Follow-on articles and reports have supported the imperative, such as a paper published by Oliver Wyman and SeaChange Capital Partners in 2016, titled Risk Management for Nonprofits, and Ted Bilich’s “A Call for Nonprofit Risk Management” in Stanford Social Innovation Review.3 Grantmakers also have identified the need for risk management; for example, in January 2017, the Open Road Alliance and Arabella Advisors published Risk Management for Philanthropy: A Toolkit to promote best practices and conversations around risk management between funders and their nonprofit grantees.4

- Nonprofit conferences and convenings have further supported this need. For example, Ahead of the Curve (AOTC), a consortium of New York City–based capacity-building organizations, came together last year to host a convening to “advance [the] collective knowledge of the discipline of risk management” within the nonprofit sector.5 The two hundred nonprofit leaders, consultants, and academics who attended were all hungry to learn.

- At the national level, groups like the Alliance for Nonprofit Management are similarly discussing and preparing to better support non-profits as they assess and engage with risk.

CRE’s own conversations with nonprofit leaders about risk, and the discussions highlighted above, confirm that: (1) nonprofits both need and desire to better engage with risk, in order to embrace risk leadership, and (2) we need a framework and tools to do so.

The intentionality implied in the above discussions suggests a change in perspective for nonprofit leaders to move beyond viewing risk management as crisis management and embracing it as necessary, forward-looking planning. This is a positive development. When organizations practice risk leadership and consistently and strategically engage with risk, they not only head off potential crises but also position their organizations to successfully fulfill their missions, grow strategically, respond to evolving community needs, and present their organizations as smart investments to savvy donors and funders.

For many organizations, this will require a significant shift—with staff and board leadership partnering closely to understand the organization’s risk profile and continually engaging with questions of risk throughout the year. In addition, many boards will have to think more expansively about risk, moving from a fiduciary-focused view (a safer and more comfortable place for many boards) to also grappling with questions of risk related to the organization’s mission and strategic direction. Staff play a critical role in helping to shape and inform these conversations by providing context, perspective, and useful data. Staff and board leadership may have to reframe the board’s perception of its role related to risk, helping board members understand the necessity and value of moving beyond considerations solely regarding financial risk and into the larger questions of mission and strategy. In our work on the ground with clients, some boards understand this right away while other boards need more coaching and support.

Consider a youth development organization that chooses to turn down a government contract that doesn’t cover the full cost of service delivery. While in the short term this could seem detrimental to mission fulfillment, it allows the organization to concentrate its energy on maximizing impact for grants and contracts that do cover full costs, while building the organization’s financial strength for the future. Or, consider a supportive housing group that proactively identifies where the risk may lie in building out a new service offering. Rather than shy away from the risk inherent in innovation, the group can demonstrate risk leadership—after an informed assessment—by pursuing the new offering while mitigating any identified risks, in order to reach the best outcome for its clients.

The practice of risk engagement is not limited to organizational leadership; it should be inculcated across all levels of staff so that it becomes interwoven into the very fabric of organizational culture. At its core, risk management is the preventive care that every nonprofit needs to remain fit and healthy. Indeed, as we enter an uncertain period when nonprofits and the communities they serve respond to new threats, the ability to engage with risk is more important than ever.

A Framework for Risk Engagement

What, then, is risk? At CRE, we define risk as an organization’s exposure to a single catastrophic event or multiple events of consequence that can harm the viability of an organization. This is similar to the definition offered by SeaChange and Oliver Wyman in their report, which defines risk as “unexpected events and factors that may have a material impact on an organization’s finances, operations, reputation, viability, and ability to pursue its mission.”6 While we often think of a single event—such as Hurricane Sandy, which devastated hundreds of nonprofits and their communities in 2012—multiple smaller events can lead to the same outcome. In short, unanticipated risks can derail achievement of strategy and mission and can threaten an organization’s sustainability.

To be sure, many nonprofits have been managing risk informally for years; if they weren’t, our sector wouldn’t be as robust or impactful as it is. But while some organizations may even engage with it intentionally—perhaps through a chief compliance officer, board risk management committee, and annual reviews—this certainly is not the norm. It is for this reason that we have invested time in defining, identifying, and classifying risks in the nonprofit sector.

CRE has developed a simple yet powerful framework and tool to help organizations think about risk intentionally and holistically. The CRE Fitness Test (CREFT) considers risk indicators and organizational activities across six operational categories and delivers an overview of a nonprofit organization’s risk preparedness. A key term here is the word holistic. We often hear nonprofit leaders discussing risk in a financial context—and, to be sure, finance is a key area in which risk may lie; however, risk can be found throughout all areas of a nonprofit’s operations, and it is often the nonobvious areas that can catch an organization by surprise.

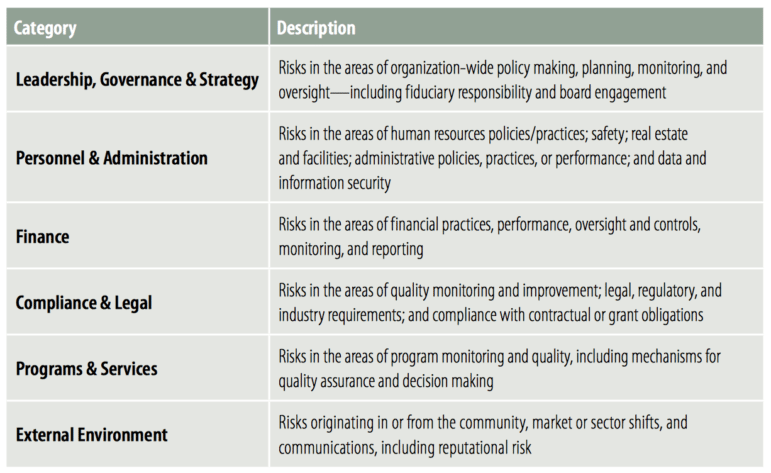

The CREFT framework comprises six categories of risk: Leadership, Governance & Strategy; Personnel & Administration; Finance; Compliance & Legal; Programs & Services; and External Environment. These categories are outlined in the table below. This framework has been tested with dozens of nonprofits and forms the basis for depicting a nonprofit’s level of risk preparedness. It is also the shared framework for risk that AOTC steering committee members will use going forward.7

This framework is meant to help a nonprofit proactively identify where it is vulnerable to risk, taking a comprehensive look at the organization. It is most effective when this is done at all levels of an organization and with input from staff and board. This process builds awareness about the many facets of organizational risk that nonprofit boards and staff should track and assess; it also enables an organization to complete the first step of a three-step process—identifying where the organization is vulnerable to risk. The next two steps involve leadership and staff assessing the potential impact and probability of those risks, followed by decisions on how to manage or mitigate the risks they consider most urgent or important.

Exploring Where Risks Cluster

In the summer and early fall of 2016—after close to a year of developing CREFT, with input from nonprofit leaders—CRE consultants, laptops in hand, tested the assessment with ten nonprofits throughout New York City. These organizations, as a group, were very diverse. They included organizations that were founded in the nineteenth century as well as those started during the Obama administration. The largest group that responded has a budget of $34 million and a staff size of nearly eight hundred people, while the smallest organization operates with a budget of $1.5 million and a staff of about twenty. These nonprofits represent a great variety of issue areas, including education, health, housing, and community organizing. In all cases, the responding staff member was the executive director or another member of the senior management team.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The ten organizations took a survey with one hundred and fifty questions grouped into the aforementioned six categories, and within those six categories are approximately twenty-five subcategories. Under Compliance & Legal, for example, questions are grouped into two subcategories: Contracts & Grants and Legal & Regulatory. For the most part, respondents answered questions based on frequency—ranging from always to never—of the presence or absence of specific practices and policies, as well as some key indicators of organizational health (e.g., number of days of cash on hand). The resulting scores provide a picture of an organization’s susceptibility to risk, or vulnerability.

After the testing sessions, respondents described a range of feelings: from validation (“We’re doing a lot of these practices”), to curiosity (“I’d like to know more about many of these practices”), to concern (“We clearly need to tighten up our practices in certain areas”). In addition to this helpful feedback about the experience of taking CREFT, we found that the very act of completing such an assessment helps to raise awareness about risk—for example, its many dimensions, where it might lie—among nonprofit leaders. Through this testing, we also received data that allowed us to develop preliminary hypotheses about where risk clusters. The paragraphs below summarize these initial findings and provide some supporting data to illustrate these observations. We insert additional perspective where useful, pulling from the input provided by the dozens of nonprofit leaders and managers with whom we have discussed risk over the last year.

Overall Risk Picture

As we reflect on the data in aggregate, one key observation jumps out: Nonprofits seem to be up-to-date and performing well for required or basic organizational practices that involve staying in compliance with legal and regulatory requirements or the basic terms of funder grants or government contracts (for example, reporting on fundraising activities and having a process for maintaining client eligibility, current for each program and service). Yet these same organizations are less consistent at implementing practices or procedures that seem more optional—for example, having the board complete annual compliance training; having some type of annual program evaluation to improve programs; or using decision-making criteria to determine whether programs should be opened, closed, or maintained. As we think about what’s required to build strong organizations that can weather challenges over the long term, these latter capacities are key to ensuring sustainability. Relatively lower scores in this area give pause for concern as we think about the health of the sector overall.

Areas of Lower Risk

Among the nonprofits that have taken CREFT to date, the following groups rated themselves highest on effectively managing risks in the categories of Personnel & Administration, Compliance & Legal, and Programs & Services.

Personnel & Administration. Personnel & Administration is a broad category containing questions about data and cybersecurity, staff management, safety, and labor-law compliance, among others. Groups reported consistently strong practices across these subcategories, and, in particular, seem adept at providing a strong policy environment around HR management and staying in compliance with labor laws and standards. Risk abounds for organizations that do not have a firm handle on HR law, so the positive practices here struck us as significant.

Compliance & Legal and Programs & Services. Not unlike the data for Personnel & Administration, the Compliance & Legal data suggest that the respondent organizations are staying on top of government financial reporting requirements and complying with key legislation such as New York’s Non-profit Revitalization Act of 2013. Moreover, and important from a risk perspective, these groups seem to be actively monitoring legislative activity and adapting to new demands and requirements. In the Programs & Services category, the responding groups once again are effectively managing some of the most significant risks—investigating client-related incidents and ensuring that clients are eligible to use their services. However, they tend to rate themselves lower around practices such as program evaluation, planning, and quality assurance, which could carry risks for these organizations down the road.

Areas of Higher Risk

Among the six categories, respondents rated their organizations lower in Finance; Leadership, Governance & Strategy; and External Environment.

Finance. In the Finance category, three items stood out as potentially significant challenges—all of which fall within Oversight & Internal Controls, the lowest-scoring subcategory.

- It appears that these respondent organizations do not consistently test their internal controls—those critical checks and balances that help organizations reduce the risk of fraud and negligence. CRE has worked with many organizations in which theft or even haphazard accounting/bookkeeping have caused or hastened an organization’s decline. Strong internal controls that are periodically tested help to prevent these situations.

- In addition, organizations do not seem to consistently monitor the costs of their employees’ fringe benefits as compared to the amounts allocated for that same expense in their grants and contracts. This could present a significant risk for organizations, especially those in more budget-constrained environments. Not having the resources to cover benefits would present a challenging set of decisions for leadership, and if optional benefits are cut or reduced, employee retention and/or morale would likely suffer, too.

- Finally, respondents report that systems between finance and program generally are not integrated, and moreover, that financial reports are not routinely provided to all departments—presumably program included. This lack of coordination and information flow between two critical organizational functions—not uncommon but of note nonetheless—could result in excess spending and unmet contract milestones (and, ultimately, reduced revenue).

Taken together, the picture that emerges within the finance area is one of organizations meeting short-term needs but less clearly delivering on longer-term financial planning and sustainability practices.

Leadership, Governance & Strategy, and External Environment. An inconsistent or weak flow of financial information between the staff and board can present significant risks for any organization, yet our test groups appear to manage this critical ongoing information exchange reasonably well. However, the boards of our test organizations seem to be getting less information about key items with potentially significant financial implications—for example, insurance claims and client and staff incidents (e.g., on-the-job injuries). This, of course, compromises the ability of these boards to provide the kind of risk leadership that their organizations really need.

Interestingly, our test organizations rated themselves lower on the use of critical management practices such as strategic and business planning, the use of key performance indicators, and even risk-management planning. These organizations could be caught flat-footed should the environment shift or change suddenly. The role of the board in helping to push for and fully participate in planning of all kinds and performance monitoring is unquestionably important.

The data suggest these organizations may be caught off guard, too, if they receive unfavorable press or are required to communicate externally about an organizational crisis. Given potential risks for our sector that are or could be coming out of Washington, it may now prove critical for nonprofits to develop and demonstrate risk leadership in these areas.

Finally, within the External Environment category, disaster/extreme weather scenarios are a clear area of vulnerability. The majority of groups reported that they are susceptible to extreme weather, but few (20–40 percent) maintain up-to-date plans to respond to facility emergencies and safety concerns, or believe that senior managers are familiar with disaster response and recovery plans. Even fewer (about 20 percent) schedule regular tests for emergency alerts and disaster response.

…

These CREFT results indicate that organizations are attending to core aspects of organizational functioning, especially what is required (e.g., mandated reporting, labor-law compliance)—yet some critical challenges emerge, such as internal controls. Some of the organizational challenges highlighted in the data have a canary-in-the-coal-mine feel to them. For example, does an under-reliance on planning—from strategic to business to risk management—portend deeper challenges for these organizations and their staff and board leaders down the road?

In the months ahead, CRE expects that more organizations will complete CREFT, adding to this growing set of data about how nonprofits are engaging with risk, and providing us with the opportunity to draw more robust conclusions about the need for risk leadership in our sector. While a small sample, our ten test organizations nonetheless provide a glimpse into areas of both effectiveness and challenge related to nonprofit risk management. Our hope is that this preliminary, holistic look at nonprofit risk helps other organizations begin to think about their own vulnerabilities, overall risk profile, and the need for risk leadership.

Notes

- See, for example, Theresa Agovino, “Major social-service nonprofit to shut down,” Crain’s, January 30, 2015.

- New York Nonprofits in the Aftermath of FEGS: A Call to Action (New York: Human Services Council, 2016), 26. (CRE president and CEO Katie Leonberger cochaired the Leadership and Management Committee of this commission.)

- Dylan Roberts et al., Risk Management for Nonprofits (New York: Oliver Wyman and SeaChange Capital Partners, 2016); and Ted Bilich, “A Call for Nonprofit Risk Management,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, July 13, 2016. (The Oliver Wyman/SeaChange report highlighted that most New York City nonprofits are financially fragile and do not have practices in place to assess and mitigate risk—for example, setting financial targets, benchmarking, scenario planning. Ted Bilich identified high-profile nonprofit failures as a call for active risk management, and offered recommendations on when in an organization’s life cycle it is best to engage in risk management—and how to begin doing so.)

- Risk Management for Philanthropy: A Toolkit (New York: Arabella Advisors and Open Road Alliance, 2017). (This report covers how the absence of risk management practices is a systemic failure across the philanthropic sector. The resulting toolkit focuses on providing guidance to funders on how to implement best practices in risk management.)

- Wendy Seligson, Ahead of the Curve Symposium: Defining, Assessing and Managing Risks at Nonprofits (New York: Ahead of the Curve, 2017). (CRE served on the Steering Committee of AOTC.)

- Roberts et al., Risk Management for Nonprofits.

- Seligson, Ahead of the Curve Symposium, 9.

Research support for this article was provided by Carlene Buccino and Associate Consultant Oseloka Idigbe.