September 11, 2017; CityLab

NPQ has written much about the increasing practice in cities with a significant nonprofit sector of asking large institutions like colleges, universities, and hospitals to make payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) for the land they take up and services they are provided. Side by side, not usually in the same conversation, cities are also engaged in bidding wars to attract large companies to their city in what CityLab is calling megadeals, corporate deals of $50 million and above. Business Week is calling this the “second war among the states…the state-eat-state competition for capital and jobs that has also been called a ‘race to the bottom.’”

The most current megadeal scenario is playing out now with Amazon, and NPQ’s home city, Boston, is one of the bidding municipalities. As Greg LeRoy, executive director and founder of Good Jobs First, points out in this article for CityLab, “it’s the third such episode in three months. Wisconsin enacted a $3 billion subsidy deal for Foxconn and the State of Iowa with a Des Moines suburb awarded $213 million to Apple.”

LeRoy asks, “Why on earth do governments keep giving corporations tax break packages worth hundreds of thousands of dollars per job—and in Apple’s case, more than $4 million per job?”

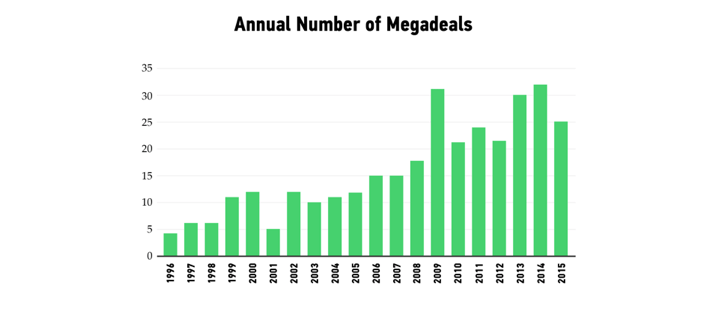

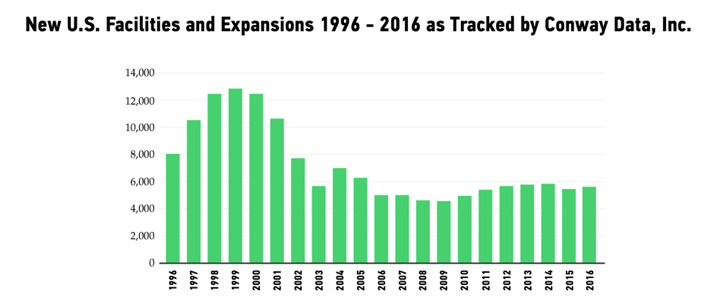

He outlines a few reasons. One is that the supply of megadeals is shrinking. “It is little known, but the total supply of economic development deals for which states and localities could compete crashed, severely, even before the Great Recession.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This creates what LeRoy calls an “asymmetrical power dynamic” where “companies are free to play states and localities against each other while the affected public officials cannot cooperate with each other. Instead, those charged with managing our public budgets passively do what they are told to do: offer more subsidies.”

There is a demand-side cause as well. The decrease in potential deals has made politicians even more anxious about securing one and appearing active on job creation. But, LeRoy notes, the average cost per job created is $658,000. “Companies can even move very short distances within the same labor market—but across a state line, as in the Kansas City, New York, and Memphis metro areas—and be greeted as ‘new job creators’ to legally qualify for huge tax breaks.”

This affects small businesses, which are severely shortchanged in this environment. LeRoy writes, “Amazon may be growing, but its competitors are shrinking, and by more, so the net effect is job churn and job loss.” The result is “overspending on deals at rates that guarantee taxpayers will never break even.”

Finally, LeRoy asserts that “this zero-sum war has been put on steroids by president Donald Trump,” who “‘personally negotiated the deal’ with Foxconn.” He writes, “The politics of Foxconn’s site location choice were as subtle as an armored vehicle manufacturer locating a factory in the Congressional District of a Defense Appropriations Subcommittee member.”

But some states are fighting back with new models.

- In bi-state ceasefires, “pioneered by 17 prominent business leaders in the Kansas City metro area,” Kansas and Missouri agreed to “deny tax breaks for intra-regional relocations.”

- The Denver and Colorado metro areas have metro no-raid/cooperation systems where, as a condition of belonging to regional economic development promotion networks, local governments must agree to no job piracy and active responses to indications that a company in a neighboring city wants to relocate.

- Capping subsidies per job at $50,000 is something many states already do for other programs.

- New York won agreement to public participation and process requirements as part of their advance-notice and deal-disclosure requirements, which are based on the idea that when taxpayers are part of the process “good things can happen.”

- GASB statement 77 data is based on a new rule from the Governmental Accounting Standards Board that “requires most state and localities to disclose for the very first time how much revenue they lose to economic development tax break programs.”

NPQ generally approves of PILOTs; we believe that it is important for large nonprofits to commit to the tax bases and sustainability of residents in their communities. But, that argument may feel harder to honor in cities that are handing out tax breaks to corporations that do not honor their own commitments.—Cyndi Suarez