November 28, 2017; CityLab

In an article at CityLab, Anthony Williams— former mayor of Washington, DC, and current head of the Federal City Council, a nonprofit that brings together much of the DC corporate elite to support local economic development—challenges the relationship between cities and mega-donors, suggesting that in too many cases philanthropic giving reinforces inequalities. This is a topic we have covered many times before; see, for instance, this article on what author Joanne Barkan describes as philanthropic plutocracy.

One example Williams gives of philanthropy reinforcing privilege is funding for parks in high-rent neighborhoods. As Williams writes, “Take a stroll through iconic public spaces like New York’s High Line and Central Park or Chicago’s Millennium Park. They are stunning. They are also enormously expensive, enormously well-gifted, and seldom surrounded by lower-income neighborhoods. They are ‘signature’ parks that the super-rich love to support.” But of course, at the same time, parks in low-income neighborhoods are often neglected.

Williams observes that while New York’s High Line and Central Park got the grants, many of the other 1,700 parks in New York City were not so fortunate. Of course, parks philanthropy can be more equitable: Williams himself cites Philadelphia’s Rebuild Initiative, a city-led initiative backed by $100 million from the William Penn Foundation, which NPQ covered this past September.

But then again, as Williams recognizes, the issue is not really just about parks. Williams writes:

In general, the mega-rich (like most of us) give to causes that are near and dear to their own hearts and experiences. They tend to give a lot to their university, and for the rich, this often means already well-endowed Ivy League schools. They also give a lot to the arts, which is wonderful. But they tend not to give much to local human services NGOs that tackle problems associated with poverty.

The role of philanthropy in American society has long generated concern regarding the concentration of political power that it implies. Rob Reich, director of the Center for Ethics in Society at Stanford University, notes in an interview with Olivia Goodhill in Quartz that:

Big philanthropy is the odd encouragement of a plutocratic voice in a democratic society. By offering philanthropists nothing but gratitude, we allow a huge amount of power to go unchecked. Philanthropy, if you define it as the deployment of private wealth for some public influence, is an exercise of power. In a democratic society, power deserves scrutiny.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

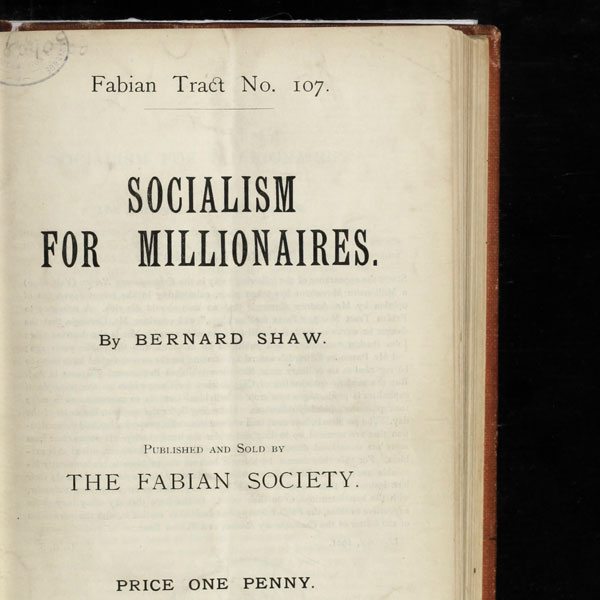

Of course, Reich is not the first to comment on the unequal relations spawned by private philanthropy. Writing in the Wire, Jacob Burak notes that in 1896, in his Socialism for Millionaires, the playwright “George Bernard Shaw quipped that a rich man ‘does not really care whether his money does good or not, provided he finds his conscience eased and his social status improved by giving it away.’”

Andrew Carnegie, one of the founders of modern philanthropy, argued that “inequality is necessary” but favored philanthropy so that “the ties of brotherhood may still bind together the rich and poor in harmonious relation.” As Benjamin Soskis writes in the New Yorker, for Carnegie, “intelligent giving would not close the gap between the classes, but would at least provide ‘ladders upon which the aspiring could rise.’” Carnegie also perversely argued that the accumulation of great wealth was necessary in order to make the libraries and museums his funding supported possible. (Judging from the Smithsonian and the Library of Congress, to give a couple of domestic examples, it would appear that public provision is also an option).

Is there a way out of this morass? There is surely no pure path, but Williams sees some hope in examples where philanthropists take a back seat to public officials and contribute to city-led initiatives. Williams points out that city governments are becoming more strategic in guiding philanthropy, with some cities creating Chief Philanthropy Officer positions.

In particular, Williams advocates “citywide, city-coordinated philanthropy”—for Williams, the Rebuild parks program in Philadelphia is one key example. Williams also highlights a smaller, four-foundation, $40 million “Reimagining the Civic Commons initiative” in four cities (Akron, Chicago, Memphis, and Detroit), which is “prototyping creative ways to revitalize public spaces like ballparks, libraries and community centers in low-income communities.”

Williams concludes on a guardedly optimistic note:

Working hand-in-hand, cities and philanthropists can work toward more democratically sanctioned goals, too. A common critique of million-dollar philanthropy is that it gives too much power to rich people to fashion public goods to their liking—without any say from the public or democratically elected leaders.

The age of mega-donations is dovetailing with the age of mega-inequality. Now is a good time to make sure vehicles are in place for citywide giving and that cities take a proactive approach to coordinating and managing big gifts.

All of Williams’ points on the inequality-enhancing effects of philanthropy are well taken, and some government/philanthropic initiatives can work well. But, there are a few not-so-small issues in all of this wonderfulness. Administrations change, as do their priorities, and not all of them are champions of the will or voice of the citizenry, as was exhibited in the now-famous interaction between Mark Zuckerberg, the Newark Schools, the community of parents, and local politicians. As with nonprofits, getting too far in bed with current city administrations may pose some problems of their own in terms of philanthropic focus, consistency and responsiveness to community.—Rob Meiksins and Steve Dubb