March 15, 2018; The Free Press, Columbus Business First, North Bay Business Journal, and Publishers Weekly

Quick: what do a grocer in Sonoma County, California; a bookstore in Cambridge, Massachusetts; a real estate company in Columbus, Ohio; and a coffee house in Rock City, Maine have in common? Answer: all four companies are converting to worker ownership.

At NPQ, of course, we have profiled employee ownership. As we noted, “a business succession crisis that could cause millions to lose their jobs is looming.” But by transferring ownership to employees, retiring business owners are able to cash out and can defer capital gains tax if the proceeds are used to purchase stock. Meanwhile, wealth is shared more widely and employees preserve their jobs. The cases featured in the press this week show the flexibility of employee ownership, both in terms of structure and industry.

California

In California, Oliver’s Market operates four stores and has $175 million in annual sales. “Structurally,” writes James Dunn in the North Bay Business Journal, “owner Steve Maass is selling 43 percent of the company to employees a bit at a time,” with ownership held by a trust in an employee stock ownership plan or ESOP. This is pretty common, as it is easier to finance a “staged transaction” than to go from zero to 100-percent employee ownership overnight.

“How we pay for it is that there’s no federal or state tax,” says Maass. “Instead of paying 45 percent tax, which was our bracket, that money pays for these loans,” Maas explains. As for the rationale, Maass confesses, “I’m 72. At some point, I have to retire. I couldn’t sell to these other guys (chains). All these people…have been with me through the whole thing. I don’t need that much money. I don’t use what I have. I built my house by hand more than 40 years ago. I have been happy with the decision to create the ESOP.”

Ohio

In Ohio, “The Woda Group…is now 100 percent owned by its employees,” reports Tristan Navera in Columbus Business First. Woda is also an ESOP. The company claims to be the “first developer geared toward affordable housing development to be organized as an Employee Stock Ownership Plan.” To date, Navera writes, “The company has developed, built or managed 300 affordable housing communities with 12,000 units in 15 states. It has a portfolio of $1.5 billion and, overall, 550 employees.” Revenues in 2016 were $82 million.

Massachusetts

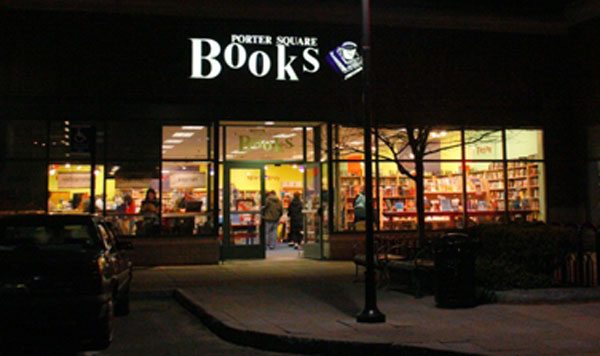

In Cambridge, Massachusetts, Porter Square Books’ “owners Dina Mardell and David Sandberg are selling half their stake…to their senior staff members,” writes Alex Green for Publishers Weekly.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“It’s amazing,” says marketing director Josh Cook, who has worked at the store for 13 years. Before this, Cook adds, “I didn’t even have a retirement plan.” Green elaborates on the financing approach, “Through the arrangement, the owners have loaned the group the money to buy half the store. With support from the profits of their ownership stake, the employees will contribute to an escrow-like fund that pays down the loan over the next decade. By the time Sandberg and Mardell are ready to retire…the staff will be in a position to complete the purchase of the store, acquiring the other half of it.”

Maine

In Maine, Rock City Coffee employees are forming a worker cooperative. Opened in 1992, “the locals gave us six months to last, but somehow we tapped into a community of artists, writers and musicians who really wanted a focal point to talk, read, play music and have book clubs,” says cofounder Susan Ward.

“In her early 60s,” writes Andy O’Brien in The Free Press, “Ward began to think about retirement, but she worried that if she sold the business, the new owner might not know how to run Rock City properly. If the coffee roastery was sold to one of her competitors, it would likely be shuttered and all of the jobs would be moved out of town. And if she couldn’t find a buyer, she would be forced to shut down a beloved community institution. But there was also a third option: selling it to her employees.”

“I thought, ‘Who better to run it than the people who built it? It’s the employees,’” says Ward. To become owners, the 17 of the 30 employees who have elected to buy in will each purchase a $2,500 share. O’Brien adds, “With all of the legal and accounting fees, technical assistance and business training, Ward estimates that the entire transition cost about $20,000. Having partially financed the deal, one of the advantages for Ward is that she will continue to receive an income stream. And the employees will get a share of the profits at the end of the year according to the number of hours they work.”

Ownership, O’Brien notes, is “not just about the profit sharing, but also about bringing democracy into the workplace.”

“Even someone who may be a barista who works part-time has a stake in the company and the direction it’s going to go in,” says roaster Kevin Malmstrom. Ward hopes others follow her lead: “Nobody here could have opened a business on their own, but as a group they had the power to buy a business. And as a group they have the power to move it forward.”—Steve Dubb