Introduction

The literature often observes that private foundations are difficult for nonprofits to access and that distribution of power between foundations and nonprofits is markedly uneven. It has been said that “whoever has the gold makes the rules.” The resource-intense nature of endowed foundations and the resource-dependence of grant seekers, taken together, combine to create a setting in which an imbalance of power is likely to exist. This can too often result in awkward foundation-nonprofit relations—also restricting foundation access. Yet, sometimes deep relationship development with foundations can reverse challenges to access and mitigate the effects of unequal power.

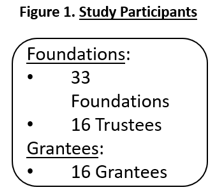

In a study conducted on foundation-nonprofit relations in 33 US private foundations, observations uncovered a set of philanthropic practices affording select nonprofits much of what is thought to be highly associated with best practices in grantmaking—namely, meaningful partnerships with more equal power sharing, organizational interdependence, mutual transparency, shared respect/value, enhanced flexibility in funding and reporting requirements, capacity to take risks, and multi-year/multi-project funding commitments.

But this does not come without expectations of grantees. Private foundations reportedly want nonprofits in return to be much more forthcoming in sharing problems that may arise and co-developing solutions, to experiment, and innovate. This article looks at this relationship from the standpoint of the culture of private philanthropy. While the following is addressed to practitioners, observations made herein are based upon formal research, which can be reviewed more comprehensively at this website.

Participant Recruitment/Methodology

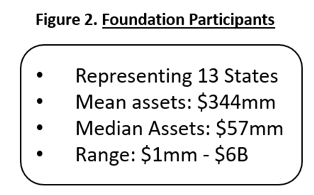

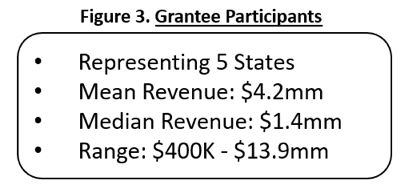

This research utilized a qualitative research methodology known as interpretive research, which seeks to develop deep knowledge/understanding of certain phenomenon through investigations guided by research questions rather than merely confirming or disconfirming hypotheses/propositions. Data was gathered from 51 interviews of foundation trustees, foundation staff, and grantee representatives, all of whom were identified and recruited through intermediaries and in a fashion consistent with purposive sampling methodologies. Foundation participants were from thirteen different states dispersed throughout the United States with a significant concentration in the Southwest.

All foundation participants were identified and recruited through foundation association intermediaries (e.g., Grantmakers for Education, Philanthropy Southwest, and New Mexico Association of Grantmakers) with the purpose of finding highly experienced/knowledgeable foundation participants with variations in location, asset size, and grant making interests (see Figures 1 through 3 for descriptive statistics of study participants). Participation by foundation trustee and staff participants enhanced triangulation of findings between governance and practitioner foundation perspectives. Foundation participants identified and recruited grantee participants, because for the purposes of this research it was important to find grantees whom foundations believed they had achieved meaningful partnerships.

I come to this work with a history of working 20 years in the private foundation world myself. I also spent another 10 years on the nonprofit side. All of the interviews I conducted were recorded, transcribed, and confirmed by participants, resulting in a significant audit trail for data and analysis. Data resulting from this large qualitative study were progressively coded consistent with emergent themes. In addition to compliance with Institutional Review Board governance and academic oversight, findings were substantiated by six independent subject matter experts.

It is important to acknowledge a potential limitation to the data in this research. Most foundations interviewed were relatively small or mid-sized in terms of their assets. It is possible that as foundations become markedly larger and more distant from where nonprofits work, they may become more procedural and less available for the kind of partnership role described herein. Participating nonprofits report that large foundations—generally thought to be above $500 million in assets, and/or which are located far from grant project activity—tend to be less willing to engage in risk-taking, investment-like approaches to grantmaking.

Private Foundations and the Influence of an Investor-Oriented Mindset

In understanding the culture of private foundation leaders that I interviewed, it is important to recognize that many were founded by entrepreneurs with careers of investing in and/or managing businesses. The world in which they operate is one that involves finding opportunities to create value in business startups and/or acquisitions. Such entrepreneurs are often energized by the challenge of creating value in unique ways, investing their time, talent, and capital. They are often inclined to embrace risk and are hands-on rather than passive. They enjoy considerable flexibility in the manner in which they invest capital. They throw themselves deeply into the businesses they own and/or operate, contributing business acumen, valuable networks, access to capital, and creativity/flexibility in how investments are structured. They are often willing to take risks when potential exists for significant returns on invested capital.

In my research, I found that the private foundations I interviewed, especially those whose founders were successful entrepreneurs, often would operate similarly in their philanthropy. That is, they seek disproportionately high social benefit (e.g., value creation) from their grants and are willing to embrace project-related risk. They are willing to experiment and risk failure if they believe potential exists for significant positive outcomes.

Of course, private foundations are routinely (and often justifiably) accused of being highly risk-averse. But in my research, I found a set of important exceptions to this pattern.

Specifically, what I found is that with some nonprofits whose missions were highly aligned with the missions of the foundations, the nonprofit benefitted from highly flexible, fully engaged, and open-minded partnerships with foundations. In these cases, both private foundations and their nonprofit partners report that private foundations are uncharacteristically driven to expand impact from their philanthropic undertakings. And that means a willingness on both sides to experiment and take risks.

These partnerships are not built in a day. Many of the nonprofits I interviewed reported that their status shifted over time. The fact that many began their relationship with the funder as a standard nonprofit grant recipient and only later were taken in as full partners enables them to make pointed observations about the pronounced differences. Nonprofit respondents uniformly reported that experiences with private foundations with whom they were considered partners were markedly different in very beneficial ways.

For this article, I will call private foundations that operate with this kind of an entrepreneurial mindset activist investors, because they seek to actively contribute time and talent, as well as treasure, to the favored nonprofits with which they partner. The following lists some key private foundation practices that participating nonprofit partners reported as being present:

• Constrained Access: Activist investors tend to attract many more proposals than they intend to pursue. It can be very difficult to gain access to pitch proposals. Such investors often rely on their networks to identify prospects. However, once you’re in, access is eased and accelerated. Foundation interviews confirmed a similar dynamic.

• High Expectations and Willingness to Risk: Activist investors generally expect to achieve disproportionately high returns, only investing where such high returns are perceived as possible. Nonprofit respondents report that the foundations they partner with possess high expectations for results and an insatiable appetite for experimentation. Relatedly, activist investors are not afraid of investments with high potential for failure, especially where the potential exists for homerun-like results from successful projects. Foundations were also reportedly willing to engage in risks when making grants. Risk was perceived as explicitly associated with potential for expanding impact. Foundations expected their grantee partners to engage in risk for the purposes of innovating. These nonprofits report that their foundation partners provide a safe environment in which to engage in risk. To illustrate a culture or risk taking, one participating founder said, “If you don’t have failed grants, you’re not taking enough risk.”

• Blurred Organizational Boundaries: Activist investors are often forward-leaning, employing extensive networks and resources to enhance the businesses they manage. They seek to leverage financial investments with their tangible and intangible resources. Organization boundaries can become semipermeable in an effort to create operating efficiencies and enhance prospects for success. For example, it is not uncommon to sit on the governing boards of companies in which they invest or even change the management in those firms.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Nonprofit partners of these foundations likewise report a common blurring of inter-organization boundaries. And, indeed, foundation representatives occasionally join their boards. Many also reported that private foundation partners provide considerable counseling and technical assistance. This includes contributing staff and/or consultant expertise, serving as advocates with other funders, and opportunities to leverage foundation prestige for grantee benefit. These nonprofits reportedly welcome foundation involvement in problem solving and project planning, because they view their foundation partners as possessing knowledge important to project effectiveness.

• Hyper Attention to Detail: Activist investors carefully study business prospects. They acquire extensive knowledge regarding investment prospects—including people, competencies, and capacities. Activist investors are acutely aware that risk of failure can be high and therefore exercise keen attention to details essential to investments and underlying firm viability. Likewise, their nonprofit partners confirm that private foundations thoroughly read their reports, make frequent site visits, ask probing questions, and offer solicited and unsolicited guidance. They add that these private foundations are interested in levels of detail uncharacteristic of other funders.

• Demand for Unqualified Transparency/Candor: Activist investors mitigate risk with timely, accurate, and comprehensive information from the firms in which they invest. They do not appreciate surprises and expect to receive valuable information early. They are intolerant of inaccurate, massaged, or misleading information. With nonprofit partners, private foundations similarly expected candid, timely, and meaningful information. Their nonprofit partners reported going to great effort to ensure that their funders learn about significant developments ahead of others.

Examples of Investor-Like Foundation Engagement

Like activist investors, private foundation engagement with partner nonprofits can be intense. The following two examples that emerged from the research are illustrative of this.

• Transitional Housing for Abandoned Children: A rural child welfare nonprofit identified a major gap in local services for homeless children. The absence of a facility to provide temporary housing pending foster care assignment too often resulted in children not having a safe place to stay, leaving children at risk of inappropriate institutionalism or possible homelessness. The nonprofit understood the child welfare system well. However, the agency neither had sufficient financial resources to acquire a facility nor the ability to plan acquisition and oversee renovation.

The agency approached a local private foundation, with which it had a strong pre-existing relationship, apprised it of the urgent need and sought assistance. The foundation determined that the agency’s vision was insufficient in terms of facility features and scale. It expanded the project’s vision, provided the initial capital, prospected possible facilities, structured the facility purchase, planned and managed renovation, and helped attract financial support from other funders after the facility opened.

This did not represent arms-length, passive philanthropy. The agency did not possess sophisticated grant writing or project-planning experience, but it had “fire in the belly” and knew how to manage operations. The foundation looked past agency limitations, recognized its competencies, and provided the financial resources and its own competencies to successfully plan and launch the project.

• Proposed Community Art Center/Museum: A local nonprofit recognized a need for a regional art center/museum for the purposes of community development and enhancing the quality of life in a rural community. The nonprofit developed a proposal that they themselves recognized fell short in many respects and presented it to a local private foundation. The proposal failed to sufficiently anticipate costs or consider other important matters such as an appropriate location.

But the foundation saw merit in the agency’s vision. The foundation directly engaged professional museum consultants to assess local needs, identify location options, find an appropriate facility, and estimate capital and operating needs. The foundation partnered with the agency and filled gaps where the agency fell short. Together, the foundation and agency planned, located, and established an arts center/museum that met the local need. Subsequently, the foundation assisted the agency attract a base of contributors to support ongoing operating expenses, resulting in a more sustainable business model.

In both of these examples, these foundations rolled up their sleeves, blurred organizational boundaries, pushed for greater impact, and leveraged their financial contributions with their institutional competencies. They also helped secure additional project support from within their networks. Both projects were in rural settings with relatively small nonprofit partners. There were additional examples where foundation partnerships with nonprofits involved more complicated projects and sophisticated financial strategies, but these suffice to illustrate what it means to operate out of an activist investor mindset.

For many funders, the above projects would have been too risky. However, these foundations looked past agency limitations, viewed themselves as catalysts in creating value, embraced risk, and contributed multiple forms of resources to expand impact. They were, in short, willing to do the hard work to realize the potential embedded in each project.

According to the nonprofit beneficiaries, this kind of foundation engagement is rare. What these examples show, however, is that private philanthropy possesses a unique capacity to embrace risk, leverage financial resources, and pursue expanded impact.

Conclusions

Even for private foundations that operate out of an activist investor mindset, not every grantee is likely to be treated in this way. However, those who do should prepare for certain expectations. Being a partner nonprofit of a private foundation with an entrepreneurial mindset means greater funding certainty and more flexibility, but it also requires that the nonprofit to invest in relationship development, comply with performance-related expectations, commit to candid and timely communication, accept greater funder involvement in operations, and take on greater risk.

Often this activist investor approach to grantmaking has been described as venture philanthropy. Sometimes, however, this language, taken from the for-profit sector, can fail to fully value the distinctive nature of the nonprofit sector.

But call it what you will, what was interesting about this study was the regularity with which I observed the development of close partnerships between nonprofits and foundations. To be clear, not every nonprofit benefitted, and even for those nonprofits that do become favored partners, the relationship becomes more equitable, but certainly not equal.

At the same time, as both the housing and the art center examples demonstrate, such partnerships are often able to achieve great things. These findings, in short, could have important implications regarding how foundations and nonprofits partner to create social change far beyond the 33 foundations examined in this study.