September 29, 2018; NPR and The Root

Affectionately known as the “Blacksonian,” the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture (NMAAHC) came under fire recently after a Twitter user questioned the appointment of a white woman to curate the museum’s hip hop exhibit. The original tweet was in reference to Timothy Ann Burnside, a specialist in Curatorial Affairs at the museum.

What seemed to be a honest question led to robust discussion, with popular Twitter users such as #OscarsSoWhite creator April Reign, Ferguson activist Brittany Packnett, and Grammy-nominated rapper Rhapsody defending her credentials and giving credence to her work as an ally. While a number of discussions surrounding Burnside’s position took place, it was clear the focus was not on her credentials but whether there was a Black person suitable for the role, especially since such positions are few and far between.

Issues of representation are not new to the museum sector (NPQ has reported extensively on this, and articles can be found here, here, here, and here.). Earlier this year, the Brooklyn Museum faced similar controversy after announcing the hiring of Kristen Windmuller-Luna to manage the museum’s African art collections. Decolonize This Place and other activists decried the choice, with Shellyne Rodriguez, who helped lead the protest, stating, “Diverse programming is not enough! It is cosmetic solidarity. The museum wants our art, our culture, but not our people.”

Essentially, Twitter commentators were questioning that same notion. In the wake of #OscarsSoWhite, #BlackLivesMatter, and discussions of gentrification and cultural appropriation, issues of museum diversity, or lack thereof, has become increasingly common. In this specific instance, being that hip-hop originated in low-income Black and Latinx communities, people are questioning the reasoning behind appointing someone outside of a living, breathing culture as a gatekeeper, especially when museums have not traditionally catered to diverse audiences. What’s more, as one Twitter user so eloquently stated,

If hip-hop is a culture—not just a genre of music—then there are nuances that the people who created and lived IN that culture will know that others will not, no matter how deeply they study the content.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In response to the criticism, NMAAHC released a statement addressing concerns and supporting Burnside’s work.

The museum is shaped and led by a leadership team that is largely African American—and the staff is firmly grounded in African American history and committed to the mission of the museum. We value that diversity and also recognize the importance of diversity of thought, perspectives and opinions. It has helped make the museum what it is today.

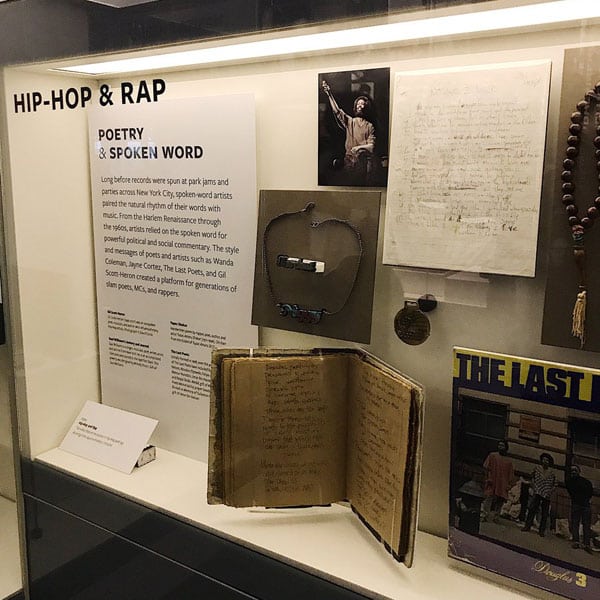

Out of a deep commitment, Ms. Timothy Anne Burnside launched the Smithsonian’s first hip-hop collecting initiative 12 years ago while at the National Museum of American History. Since joining the Museum in 2009, she has also played a key role in building the hip-hop collection as part of a larger curatorial team. Dr. Dwandalyn Reece, the curator of music and performing arts, leads that effort. We are proud of their work.

The statement also notes the lack of African Americans in curatorial positions and their current efforts to address the issue through paid internships and fellowships. Since then, the museum has released a feature article highlighting Black curators at the institution in addition to some of the current initiatives it is undertaking in DC public schools to encourage more people of color to consider careers in museums.

One thing of note in this entire fiasco was the seeming lack of concern regarding the optics of appointing a white person to what is considered one of the largest institutions focused on African American history in the country. Since its opening, NMAAHC has experienced record attendance, with more than 3 million visitors having walked through the 400,000-square-foot building. In a field that is constantly reinventing itself to remain relevant to a changing demographic, it’s surprising that the museum did not take extra steps to introduce the public to Burnside’s work. The museum’s oversight may make people wonder about its commitment to stakeholders and question who it actually considers its stakeholders. In an act of transparency, maybe they should take a note from the Cleveland Museum of Art, which recently released its strategic plan explicitly detailing how it intends to engage the community—not simply through attendance, but through hiring decisions, selected curated art, and organizational policies.

NPQ has published a number of newswires on the development of pipelines for curators of color at HBCUs and elsewhere, but the museums will also need to create internal systems to train and promote leaders of color for prized curatorial roles. They owe that to the public and to themselves, and apparently the public is growing unwilling to accept any less.—Chelsea Dennis