December 3, 2018; Chicago Business

Rush University Medical Center, author of the Anchor Mission Playbook published last year, is widely seen as a nonprofit hospital leader in addressing community needs. As Alex Kacik writes in Chicago Business, in 2017, Rush, working with a community coalition known as West Side United led dozens of “learning map” meetings throughout Chicago’s West Side “to learn what residents needed and how to meet those needs.” But as Kacik points out, not all hospitals are like Rush. “Without explicit rules guiding hospitals’ interventions or setting a baseline level of funding, community benefit programs and their spending vary wildly,” Kacik explains.

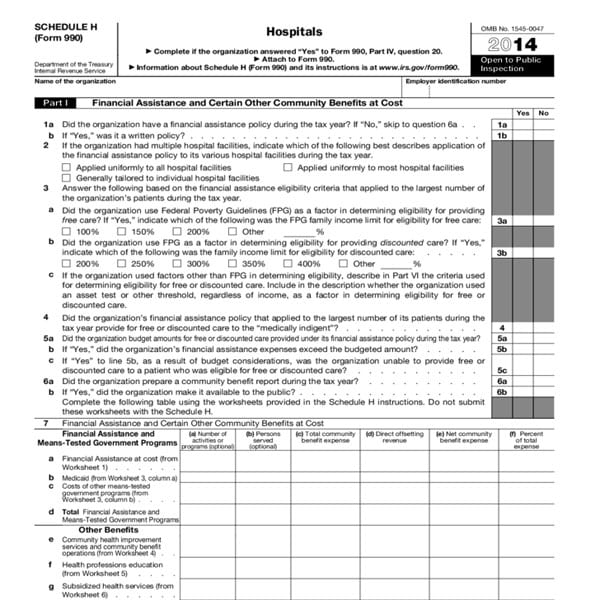

Community benefit is a term used by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to denote community-based activities performed by nonprofit hospitals. The IRS requires nonprofit hospitals to fill out their Schedule H on their Form 990 filings to detail the work they do on the community’s behalf. Unfortunately, expecting a tax collection agency to be an effective overseer of the public health benefits of nonprofit hospitals is a tall order. And most often, the existing regime falls short.

The stakes are high. On Chicago’s West Side, which corresponds to Rush’s service area, West Garfield Park residents can expect to live 69 years, while six miles away, residents in the high rises of the Loop have a life expectancy of 85 years. “Problems identified in the West Side,” Kacik notes, “ranged from a lack of major grocery stores to unchecked mental health issues and systemic racism that keeps the school-to-prison pipeline flowing.”

But, by and large, as Kacik details, community benefit strategies still largely fail to address such social determinants of health. This is true even though up to 90 percent of all health outcomes have to do with factors other than the presence or quality of clinical care.

Gary Young, director of the Center for Health Policy and Healthcare Research at Northeastern University, tells Kacik that the business model is still one that requires hospitals to fill beds, even if filling beds does little to achieve better health outcomes. “They often don’t have the resources, infrastructure or capacity to focus on broader community health issues,” Young says.

Then there are the gaps in what the feds consider to be community benefit. One large category is charity care, or free or subsidized services. Other areas include “health professions education” costs, such as workforce training and development; outreach programs, including community health improvement services and direct cash; and subsidized health services and research.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

It gets worse. As Kacik notes, “Hospitals in low-income areas have to spend more on free and subsidized care, which means they spend less on preventive community programs. Conversely, hospitals in affluent areas have the flexibility to spend more.”

“It’s a vicious cycle,” Young tells Kacik.

The narrative section of Schedule H of IRS Form 990 allows for great flexibility, notes Kacik. Claims can be made for “health screenings, hosting behavioral health support groups, opening outpatient clinics for specialty care and hiring new chronic disease doctors…participation in hospitals’ online portals, offering online educational materials…promoting preventive-care resources on its website, provider-to-provider telephone consults, and sponsorships focused on wellness and healthy eating.”

Yet the field is recognizing the systemic shortfalls. “With the increasing focus on social determinants of health, hospitals and systems are realizing that public health issues need to be tackled together,” Kacik observes. The Health Impact Collaborative of Cook County, a group of 26 hospitals, seven health departments and nearly 100 community organizations released a 243-page report in 2016 that calls for “improving social, economic and structural determinants of health, improving mental health and decreasing substance abuse, preventing and reducing chronic disease, and increasing access to care and community resources.”

Slowly, the federal government is catching up. Last month, US Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar indicated that Medicaid may authorize hospitals to directly pay for housing, healthy food, or other needs that improve health outcomes.

Bonnie Condon, vice president of community health and faith outreach for Advocate Aurora Health, notes that, “The evidence shows that health fairs and screenings don’t make a big difference. What does is working on access and health equity and impacting other social conditions.”

As Kacik writes, “In the current Form 990 framework, community building activities are not counted in a hospital’s total community benefit spending, which could deter investment in those areas. Those building activities include physical and environmental improvements and housing, and economic, leadership and workforce development.”

Julie Trocchio, senior director of community benefit and continuing care at the Catholic Health Association, concurs. Trocchio notes that, “When researchers and the press often look at our 990, they just look at that front page and the bottom total and they don’t look at the total numbers, including community building activities. We’re afraid it is a disincentive.”—Steve Dubb